The State Of Women’s Representation On The Eve Of The 2016 Election

Hailed by some as a second “Year of the Woman,” the 2014 election was a positive — but by no means watershed — election for the advancement of women’s representation. For the first time, over 100 of the 535 members of the U.S. Congress were women. Additionally, New Hampshire became the first and only state to reach gender parity in elected office according to Representation 2020’s Gender Parity Index. Yet, only five female governors were elected in the 36 gubernatorial races held in 2014 and Americans elected fewer female state legislators than in 2012.

Let’s reflect on where women’s representation is at in the lead up to the 2016 elections.

Measuring women’s representation: Representation 2020’s Gender Parity Index

In order to quantify progress toward gender parity in elected office, Representation 2020 developed the Gender Parity Index. Each year, a Gender Parity Score is calculated for the U.S. and each of the 50 states. The Gender Parity Score measures women’s recent electoral success at the local, state and national level on a scale of 0 (if no women were elected to any offices) to 100 (if women held all such offices). A state with gender parity in elected office would receive a Gender Parity Score of 50 out of 100.The key advantage of the Gender Parity Score is that it enables comparisons over time and between states.

Only five states were more than three-fifths the way to parity in the lead up to the 2016 election

Overall, progress toward parity was made in 2016. The median Gender Parity Score in the 50 states increased from 18.1 at the end of 2014 to 18.7 in October 2016. However, only five states received a Gender Parity Score of more than 30 points: Arizona, California, Minnesota, New Hampshire and Washington. An additional seven states are one fifth or less of the way to gender parity in elected office: Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Utah and Virginia.

The Gender Parity Index shows that we are less than halfway to gender parity

Both the first “Year of the Woman” election in 1992 and the 2014 election advanced women’s representation. It is important, however, to keep those advances in perspective. Current strategies to advance women’s representation have gotten us less than two-fifths of the way there — 96 years after the ratification of the 19th Amendment guaranteeing suffrage to women. We can’t wait another 96 years (or longer) to reach gender parity in elective office. Representation 2020 understands that it is important to train and fund more women candidates. In addition, however, we need structural reforms — of candidate recruitment practices, electoral systems, and legislative rules — that level the playing field to hasten our progress toward gender parity in elected office.

New Hampshire leads the nation

New Hampshire ranks highest in our 2016 Parity Index with a score of 55, slightly above gender parity in elected office. The state scored 9.9 points higher than the second-placed state (Washington). In 2012, New Hampshire was the first state in the nation to elect an all-female delegation to Congress — and currently 3 of its four-member congressional delegation are women. The current governor is female (Maggie Hassan, who is running for U.S. Senate in 2016), 29% of its state legislators are women, and the mayor of the state’s fifth largest city, Dover, is a woman. New Hampshire was also the first state in the nation to have a majority-female state legislative chamber (state senate from 2009 to 2010).

Mississippi ranks last

Mississippi received the lowest Gender Parity Score in the nation with just 6.4 points. As we head into the 2016 election, Mississippi is the only state that has never elected a woman to the governor’s mansion or to the U.S. Congress. The 2016 election will not change that: there are no female major party candidates running for the U.S. House, and no races for U.S. Senate or governor. Only four women have ever served in statewide elective office in Mississippi, 2 of whom are in office today. None of Mississippi’s 9 cities with populations greater than 30,000 people currently have female mayors.

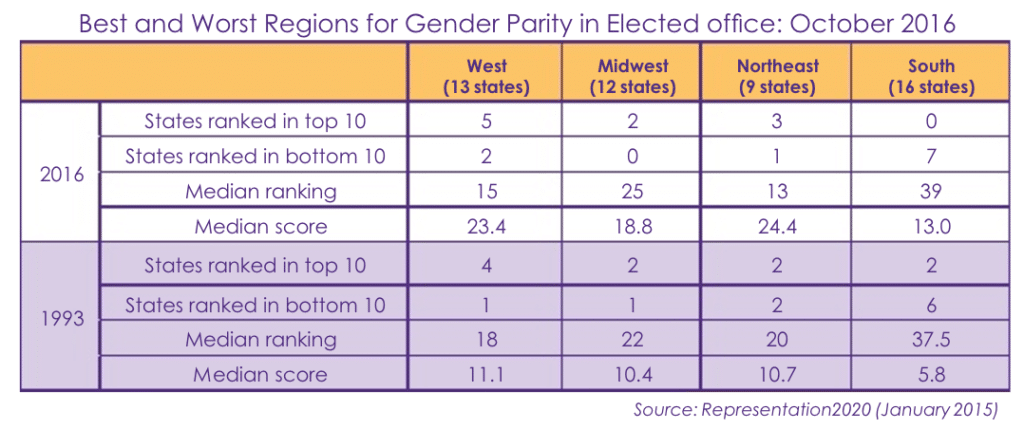

Regional Trends: The Northeast and West excel, while the South lags behind

The West and the Northeast outperform the Midwest and the South in gender parity in elected office. Eight of the 10 states with the highest Gender Parity Scores in July 2016 were in the Northeast or West (Arizona, California, Hawaii Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico and Washington). By contrast, seven of the 10 states with the lowest Gender Parity Score are in the South (Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas and Virginia).

The disparity between the South and other regions has widened in the past few decades. In 1993, two southern states (Maryland and Texas) ranked in the top 10 states for gender parity, while six (Alabama, Louisiana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) ranked in the bottom 10.

No state legislative chambers are at parity

In the lead up to the 2016 election, not a single state has gender parity in its state legislature. The legislative chamber closest to parity in the nation is the Colorado House of Representatives, with 46.2% female legislators. In November 2014, 50 female candidates ran for the 65 seats in the Colorado House of Representatives, according to the Center for American Women and Politics, and 30 were elected. Not surprisingly, Colorado ranked first for the proportion of women in its state legislature, with 42.0% female state legislators in July 2016. Ranked lowest was Wyoming at 13.3%. In 1993, the range was from 39.5% (Washington) to 5.1% (Kentucky)— showing advances for the lowest-ranking states, but less improvement for states at the top.

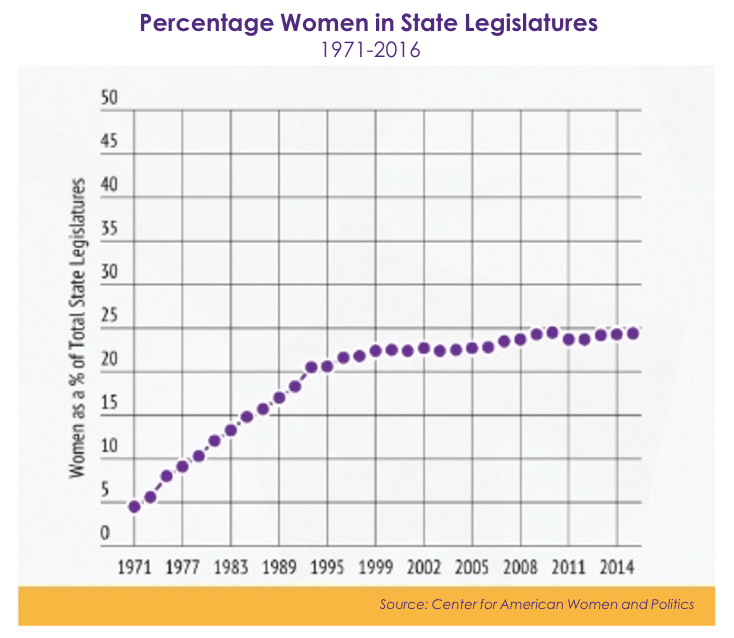

Fewer women in state legislatures

The proportion of women state legislators actually declined slightly as a result of the 2014 election. Currently, 1,791 (24.3%) state legislators are women. If we take a broader view, we can see that the progress toward gender parity in state legislatures is slowing down from the 1970s, which is worrying. Without new initiatives, progress may stall completely.