My Parents Proudly Worked For The US Postal Service

When I was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, my family planned our vacations around big picnics for post office employees. I remember the thrill of taking the train from San Francisco to one of these gatherings in Santa Cruz.

For my parents, both longtime postal employees and union officers, that was their community. Back then, it was mine, too.

Today, the U.S. Postal Service is under pressure to slash costs in ways that would be devastating for customers and employees of all races — but especially African Americans. For black families like mine, the Postal Service has long been one of the few reliable paths to the middle class.

My parents were so proud in 1957 when they had saved enough money to buy a house. They sometimes held union meetings in our living room and had me put my seventh-grade typing skills to good use addressing envelopes for the union newsletter.

The black postal workers I met back then felt good about who they were and optimistic about where the country was going. The civil rights movement was gaining strength, and the post office was one arena in which they could organize for equality.

Black families will be hardest hit

Today, the Postal Service remains a critical source of good jobs for African Americans. Black employees make up 28.6% of the postal workforce — more than double their share of the U.S. population.

In 2018, average Postal Service wages were $51,540 a year, just slightly below the average for all U.S. workers. According to the Institute for Policy Studies, wages were substantially lower in the nine other occupations in which blacks make up at least 25% of employees. For example, home health aides, 26.1% of whom are black, averaged just $25,330 per year. Barbershop employees, 30.8% of whom are black, earned $33,220.

These numbers make clear why black families stand to be the hardest hit by the Trump administration’s proposals to sell off the Postal Service to for-profit corporations. A presidential task force plan to move in that direction calls for privatizing parts of the service, reducing delivery days, closing post offices, and jacking up prices on most package and mail deliveries.

It would also get rid of the collective bargaining rights that have helped postal workers maintain decent wages. My parents’ generation fought for and won those rights in 1970.

Privatizers say such moves are necessary because the Postal Service is in a financial crisis. But Congress manufactured this crisis through a 2006 law that required pre-funding of employee retirement health benefits up to the year 2056 — a stunning 50 years in advance of when the law was passed. No other federal agency or private corporation faces this burden, and without it the Postal Service would’ve been profitable the past six years, according to a December report by the Treasury Department.

Real reforms expand service

Instead of more cuts, policymakers should do away with the onerous pre-funding mandate and explore new profit sources, such as postal banking. One government report found that expanding services such as check cashing, bill payment and electronic money orders could generate as much as $1.1 billion in annual revenue after five years — all while dramatically expanding financial services for low-income Americans.

Here again, there’s a lot at stake for black families. As Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez noted in a recent statement in support of postal banking, low-income Americans lack access to regular financial services and have to resort to predatory payday lenders and check-cashing outfits. And African Americans and Latinos make up a disproportionate share of the 64 million underbanked Americans.

Throughout our nation’s history, the Postal Service has responded to changing needs while continuing to advance the common good. In the 19th century, the Pony Express and Rural Free Delivery helped bind the nation. During the Civil War, postal money orders allowed Union soldiers to send funds home safely. From 1911 to 1967, people who had lost confidence in banks could deposit their money in a postal savings account.

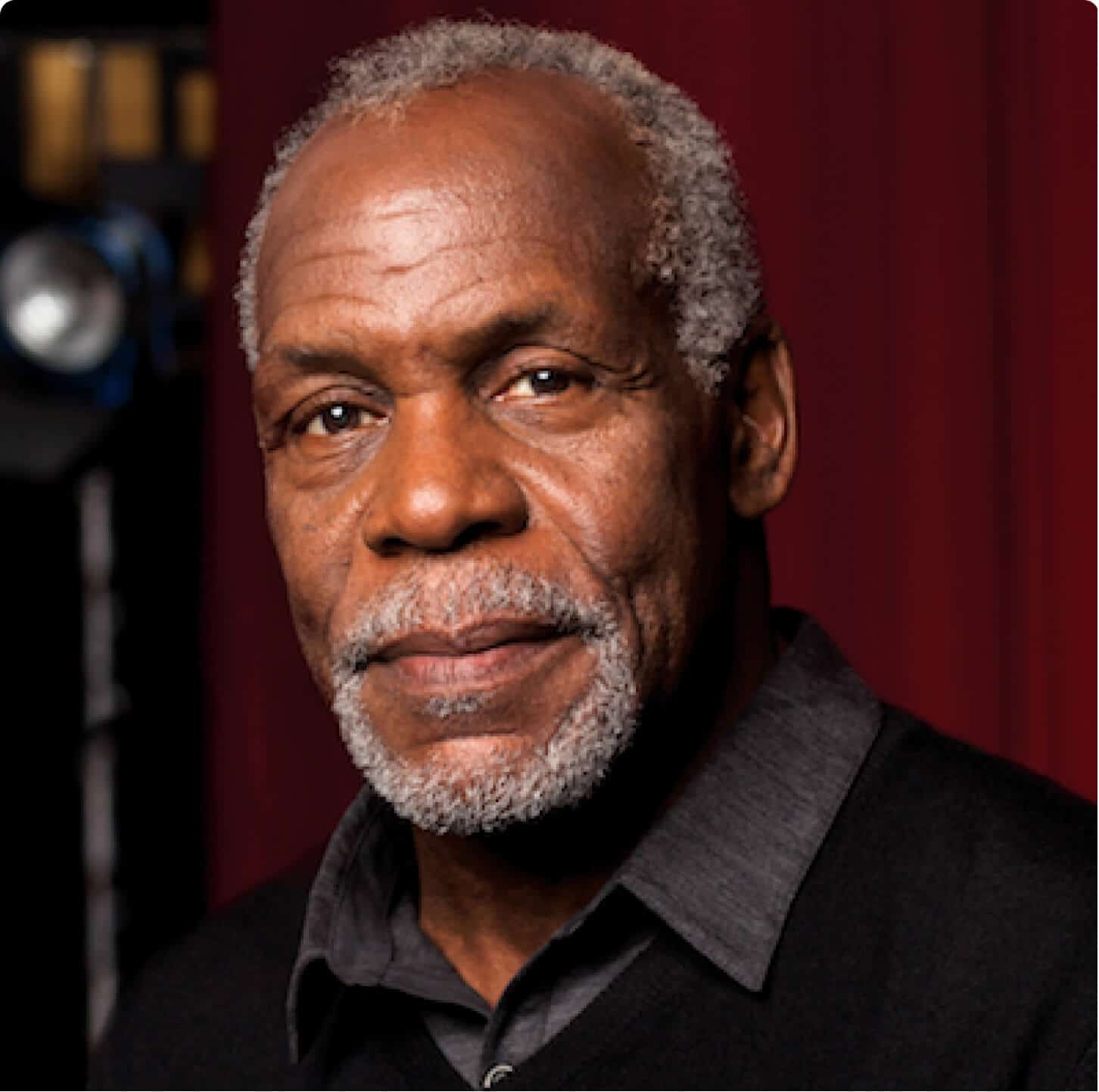

To this day, I still run into people who remember my dad, Jimmy Glover, as the man who trained them to sort mail by hand and treated them with dignity on the job. To them, he was the real celebrity in our family.

We must protect the Postal Service — and support new innovation to meet 21st century needs. We owe it to my parents and the millions of others who built this vital public infrastructure.