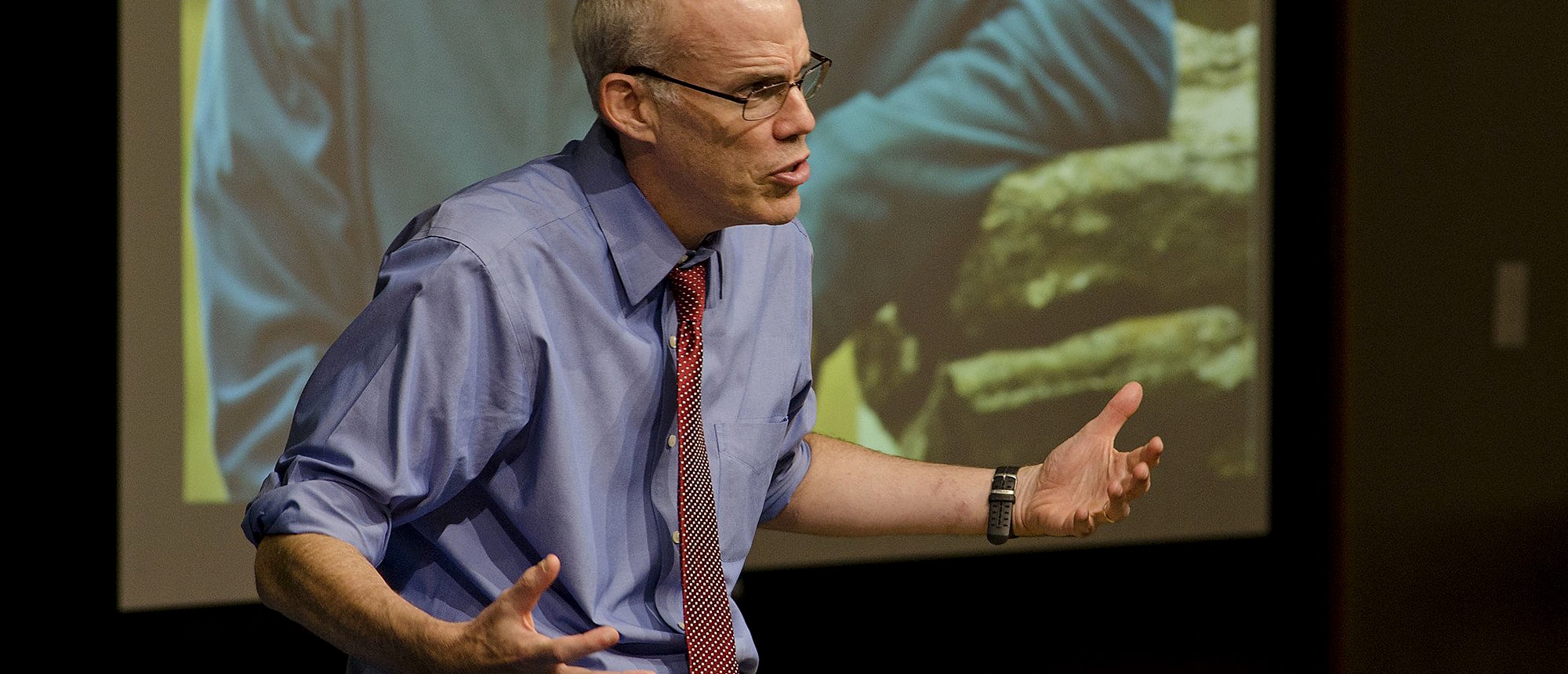

Bill McKibben Discusses A Decade-Long Activist Crusade To Shame Banks Into Stopping Investment In Fossil Fuels

When Bill McKibben sought to put the fossil fuel industry out of business, he made his case in the media. Then he took his show on the road.

Hitting roughly 27 cities in 29 days in the fall of 2012, the prominent American author, climate activist and co-founder of 350.org sold out venues across the United States, introducing thousands to the idea that by pressuring institutions — universities, faith-based groups, banks, pension funds — ordinary people could force huge sums of money away from the coal, oil and gas companies fuelling the climate crisis. By the time the roadshow wrapped up, calls for divestment were sprouting on 300 college campuses nationwide.

The movement only grew from there. Today, as lethal flooding and heat waves put climate action front and centre around the world, a global campaign to divest from fossil fuels has taken hold in boardrooms, on university campuses, among faith groups and beyond. Earlier this year, that campaign reached a milestone: more than 1,500 institutions with $40 trillion in assets under management committed to divesting from fossil fuels.

In an interview with Canada’s National Observer, McKibben unpacks the ties between fossil fuels and colonialism, the art of shifting an industry’s social licence to operate and how the movement is spawning a new generation of politically engaged citizens on college campuses around the world.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Today’s push to divest from fossil fuels was inspired in part by earlier divestment campaigns against South African apartheid. Why was this such an effective strategy?

Back in apartheid times, there were relatively few levers that people had in the west to put pressure on South Africa. This was the Reagan era, so the government wasn’t going to do anything. But pressuring South Africa’s financial backers proved very useful. So when we were thinking about this, one of the first people that I got in contact with was Desmond Tutu, who had won the Nobel in part for his work around that, and I said, “Do you mind if we borrow this tactic?” ’Cause we didn’t want to just do it without asking, and he said, “Please, please. If apartheid was the human rights issue of a generation ago, then climate change is the human rights issue of now.” And he went on to be very helpful on this work, including managing to get King’s College London, which was one of his alma maters, to divest from fossil fuels. And so that connection back to apartheid was really crucial because it taught people how to do this.

Can you talk about the other link between South Africa and North America: the shared history of oppression of Indigenous groups by a settler group. What are the similarities and differences, and how does divestment work as a strategy in that context?

It shouldn’t be a huge surprise that the fossil fuel industry is the perfect example of a colonial enterprise. Fossil fuel is concentrated in a few places around the world, so controlling those places is key. It’s why the fossil fuel industry hates renewable energy so much. The sun is diffuse and exists everywhere, so there is no way to monopolize its output. This has been a link all the way back to the beginning of this work on the financing of fossil fuels.

The first divestment push I heard of was the work Indigenous leaders in Canada were doing around the tarsands — going over to Europe to try and get banks to stop financing them.

That tactic, thinking about the financing of all this, has a history and much of that history is tied up with the powerful use of it by Indigenous communities.

A lot of the push for divestment is coming from college and university campuses. For many of the young activists, it’s their first time, getting involved in social movements. Does divestment then function as an on-ramp to the climate movement more generally?

Yes, and this one’s not speculative because the history is extraordinarily clear. Probably the most important part of the recent environmental movement in the States, at least politically, is the Sunrise Movement, which brought us the Green New Deal and the legislation that descended from it. They shook up things. Almost all of the leaders of the Sunrise Movement, the people who founded it, cut their teeth doing divestment work in college and wanted to keep on after graduation and moved onto politics, in a sense.

Sunrise’s founding executive director, Varshini Prakash, successfully led the fight to divest from fossil fuel when she was a sophomore at the University of Massachusetts. It was an early win in the divestment campaign.

So there’s no question that by allowing this fight to go on at thousands of different places, it’s brought up thousands and thousands of able leaders.

How does the fossil fuel divestment movement fit with other tactics?

It’s always going to be a multi-pronged strategy, but all of it is aimed at, in the largest sense, weakening the power of the fossil fuel industry. Our analysis from the beginning identified this as the single biggest factor standing in the way of doing what scientists, economists and everyone else is telling us we should be doing. Without that vested interest, we’d be making way more progress. So the social licence part was our original goal, and I think it’s been highly effective in that way. Young people are no longer under any illusions about the fossil fuel industry, for instance. They understand it to be a predatory, self-interested [industry] that’s imperilling their future in obvious ways. The whole divestment movement got big enough that it began to interfere with industry’s ability to access capital. This was clearest early on, especially in the coal industry, where you begin to hear executives complain they couldn’t raise money anymore because there were so many funds that were closed to them.

When Peabody Coal filed for bankruptcy some years ago, they listed divestment as one of the reasons. Divestment has now extended into the oil and gas realm. Shell, in its annual report two or three years ago, said divestment had become a material risk to its business, which pleased me because Shell’s business is a material risk to life on the planet. So having taken $40 trillion off the table for these guys is no small feat, I think.

All of this has led to a profound shift in the zeitgeist and the understanding of what’s normal, natural and obvious. When we began, these oil companies were the biggest companies in the world, and their power seemed unassailable. They’re still very strong but they’re shadows of themselves in certain ways, too.

No tactic wins by itself. There are many fronts in this fight, but divestment has been an important one. It’s helped people understand straight-ahead politics is not the only way. You can make change in [other] ways. The metaphor in my mind is that there are two levers big enough to make change in the climate picture at this point. One of those levers is marked politics, the other is marked money.

Instinctively, we pull the politics lever because it seems like that’s where change comes. But I think it’s been important that we’ve been yanking on this other lever, too.