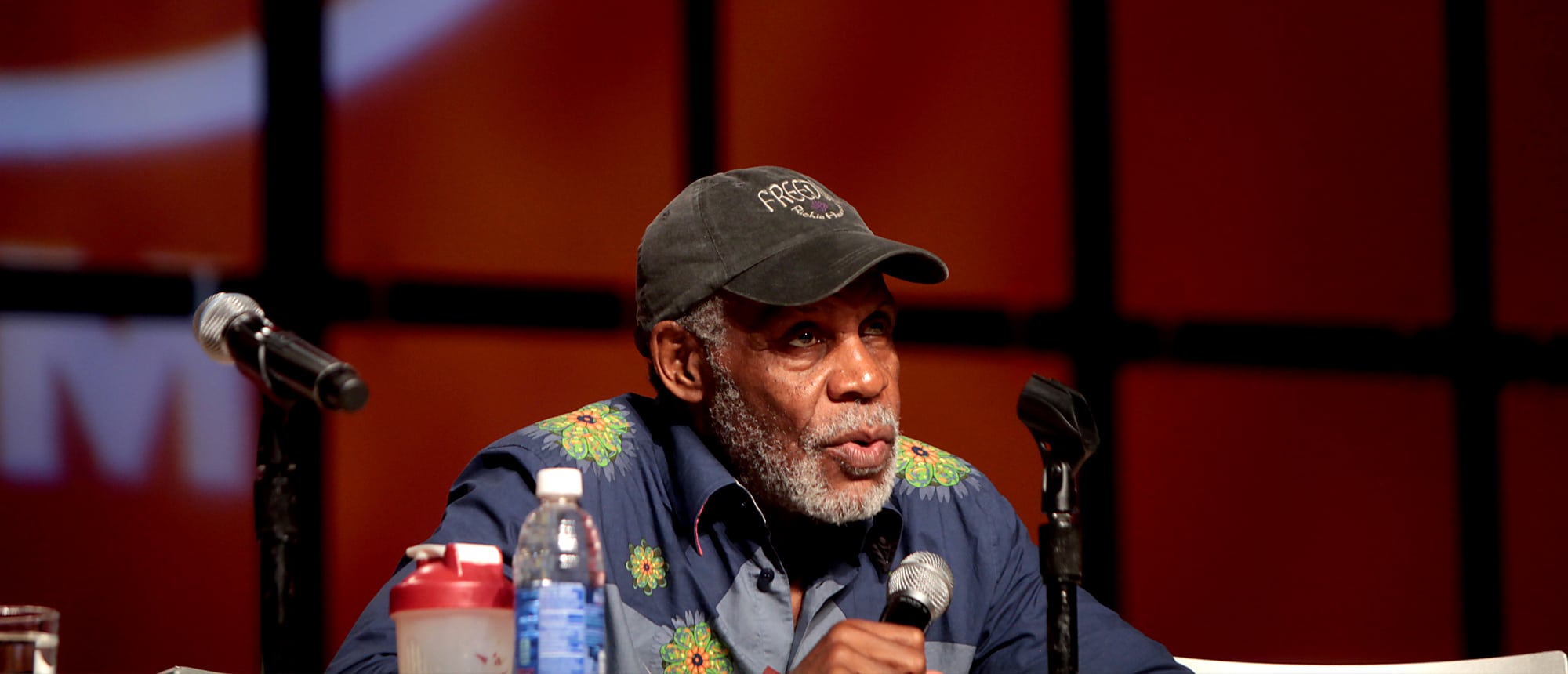

Danny Glover On George Floyd

Danny Glover was recently a juror and mentor at Turkey’s virtual International Migration Film Festival, for which he took a deep dive into films tackling the plight of migrants around the world from his home in San Francisco, just as protests over the death of George Floyd escalated in the U.S. The actor-writer-producer and passionate political activist spoke to Variety about how he’s been associating the current global migrant crisis with the historical roots of violence against African Americans in the U.S. The screen icon, known for classics such as “Places in the Heart,” “The Color Purple” and the “Lethal Weapon” franchise, also discussed his parallel career as a producer of socially relevant films by global auteurs, such as Cannes Palme d’Or winner “Uncle Boonmee who can Recall his Past Lives,” and why “Lethal Weapon 5” should come back “within the political framework that we are in.”

What’s your biggest takeaway from the movies you saw about the migration crisis?

As an American citizen, we see glimpses of it on the news, and we know that there is a crisis happening. We see the actual reporting. But we don’t understand the entire stories that are engaged, and the historic nature of those stories, particularly in Afghanistan, which we’ve heard so much about. So (in “Just Like My Son,” by Costanza Quatriglio), the story of a young man trying to find his mother after not seeing her for years and years, it’s a touching personal story. And it has its own power, with respect to seeing it in a much larger context. That personal story has a much stronger impact in understanding the crisis that we are in…You see the magnitude of the crisis, yet we are immune to it in this country. In America, there is a kind of certainty of expectations that the government is able to protect you, to some extent. Except in some neighborhoods, in some communities.

Such as South Minneapolis.

There is an outcry after the murder of George Floyd — or there is an outcry after Eric Garner — which in some sense is expecting resolution in this country. But the question of migrants has existed internally in this country.

As an African descendant from enslaved Africans – who either escaped as migrants, and after the Civil War and after they were freed became constitutional citizens – they still were forced to migrate to various places in the country to escape the violence that they themselves experienced. The emotional and physical violence; the lynchings and murders. They were internal migrants within the country itself. Even though the country posed this certainty for other citizens, it didn’t pose this kind of certainty for them.

So when I saw these different stories they made me think about this. You think about mothers sending their daughters away once they became 13 and [when] white men and white boys started looking at them. They sent them from the South somewhere North or somewhere else where they could be safe. This is something that is not often expounded upon in our historical narratives. Or parents of young boys having them leave the South because of the possibility of their being lynched. Or escaping the violence that is inscripted in the 400 years of this country’s history towards enslaved Africans, or formerly enslaved Africans.

Do you think, this time, the Black Lives Matter movement can make a difference?

It has to be seen. We don’t know what’s going to happen in this particular moment. The resources and the allocations that are going to be thrown at this; the choices that are going to be made are going to be numerous. But the violence that we see – whether it’s the toxic places where they (black people) live; the inadequacy of health care for them; whether it’s the lack of affordable housing; the absence of jobs at living wages; all those things – that’s basically going unseen. We see the actual violence because the police is what it is. It’s the last line of defense for white supremacy. That’s what the police represents. They don’t protect African Americans. You can make an argument that the institutional violence has its roots in so many different ways. The violence that we see now that is acted out on the physical body of George Floyd has been the kind of violence that is engrained within the American idea of its culture, in its own subtlety, since the first Africans were brought here. So it’s 400 years of violence. It’s not just now!

As James Baldwin said: when we cannot tell ourselves the truth about our past, we become trapped in it. This country has been trapped in its past and continues to be. It’s even trapped in its past in terms of First Nations people. We never hear about the violence on First Nations people.

What does real change look like? That’s the question at a moment in time when we shape the images of change, and they might not be the kind of substantial changes, qualitative changes and transformative changes that are necessary.

What would the change look like in terms of narratives coming out of Hollywood?

It may be a democratization of what I call cultural production. Cultural production looks at: how do people live? How do we understand each other? What are the elements that bring us together and form the whole idea of the responsibilities that we have to each other as human beings? How do those kinds of stories evolve? It must not only happen within my business. It has to happen in concert with all the kinds of relationships that we have. We have to be honest about that. As I said before, we can’t be honest about what we are. We fantasize about what we think should be changed. What does that mean?

I think we started having a different sense of African Americans [on screen] when the civil rights movement came about. The new images of African Americans presented by Hollywood came through avenues that were opened because of singular artists at the time. Sidney Poitier changed the whole image of African Americans. Every one of us: me, Morgan [Freeman], Denzel [Washington], Sam [Samuel Jackson] we are descendants of the images presented by Sidney Poitier!

I think there has to be some sort of sound way, because we can’t go back to just anything…In terms of saying: we are going back to the past. We can’t go back.

Those people who are white and Black and brown and gay and LGBTQ — all of them are saying, as they march in the streets: we can’t go back! That’s the message that’s on the street right now.

Of course, you’ve been fostering a different type of cultural production for years as a producer with Louverture Films in partnership with Joslyn Barnes.

I had the advantage when I started out of doing the plays of the great South African writer Athol Fugard as my foundation for looking at cultural production. And that was in the midst of the Anti-Apartheid movement and the Free Mandela movement. I’ve also had this fascination about world cinema. When I was working, I would often go to arthouses and watch world cinema.

So the idea that came around with Joslyn Barnes started by talking about the Haitian Revolution. Now somebody might have thought that was a rock band, but there was a Haitian Revolution [led by Toussaint Louverture]. Haiti was the first nation ever to be formed by formerly enslaved Africans who defeated the Spanish, defeated the French, defeated the British. That’s how the conversation started.

Then we talked about our interest in world cinema. And we began to say: how do we put emphasis on this issue? So we put emphasis on storytellers. Elia Suleiman, Palestinian, one of the great filmmakers in the world. How do we get involved in that?

Apichatpong [Weerasethakul] from Thailand, “Uncle Boonmee who can Recall his Past Lives.” Brilliant. I could have shown that movie to my grandmother, who was born in 1895, and she would have gotten it! My grandparents, they would talk about past lives; about visions. They would sometimes scare the hell out of me as kid! And so those are the kind of things that we were able to do.

What about your career as an actor?

There are things that I’ve done that are no doubt important. “The Beloved” is an important film; an extraordinary film. “The Color Purple” is an important film. “Places in the Heart,” with Sally Field, is an important film for me. They moved my career in a lot of ways, but they were important for me to do. Because they were also expressions of part of that psychic history that’s in my bones, that comes from my great-grandmother, who was born in 1858. All that history is a part of me. So being able to do those films is a way of exploring that part of myself.

But also the opportunity to have a franchise film, and to try to do something with that franchise film. And that’s basically what Richard Donner and the creators of “Lethal Weapon” did. One [film] was about drug proliferation; one was about arms proliferation. One focused on South Africa. There’s value in that as well.

In January it was reported that producer Dan Lin said there are plans to do another “Lethal Weapon” sequel with you and Mel Gibson on board. Is there any truth to that?

There has been a conversation about that in January. I don’t want to give away the plot on the script that I read, but I found the plot had very strong relevance to some of things that are happening today. I can say that. But that was in January. History changes so fast…But yes, there’s been talk about it. There is something of a plan.

Would you like to do it? Sounds like you liked the script.

Yes, I liked it. I can only tell you, if it does happen, there is something extraordinary in it. If “Lethal Weapon” gives us some sort of contribution to understanding a little bit more…It would be interesting to do. It would be interesting to see how we take this within the political framework we are in; the economic framework that we are in. And especially that framework as opposed to the communities that have been affected by the kind of police violence, the kind of police standards, and the power that they exert as well. And what would be interesting from that vantage point is what that attempt could be like at this particular moment.

And maybe it will attempt to confront the issue head on, within whatever script comes out.