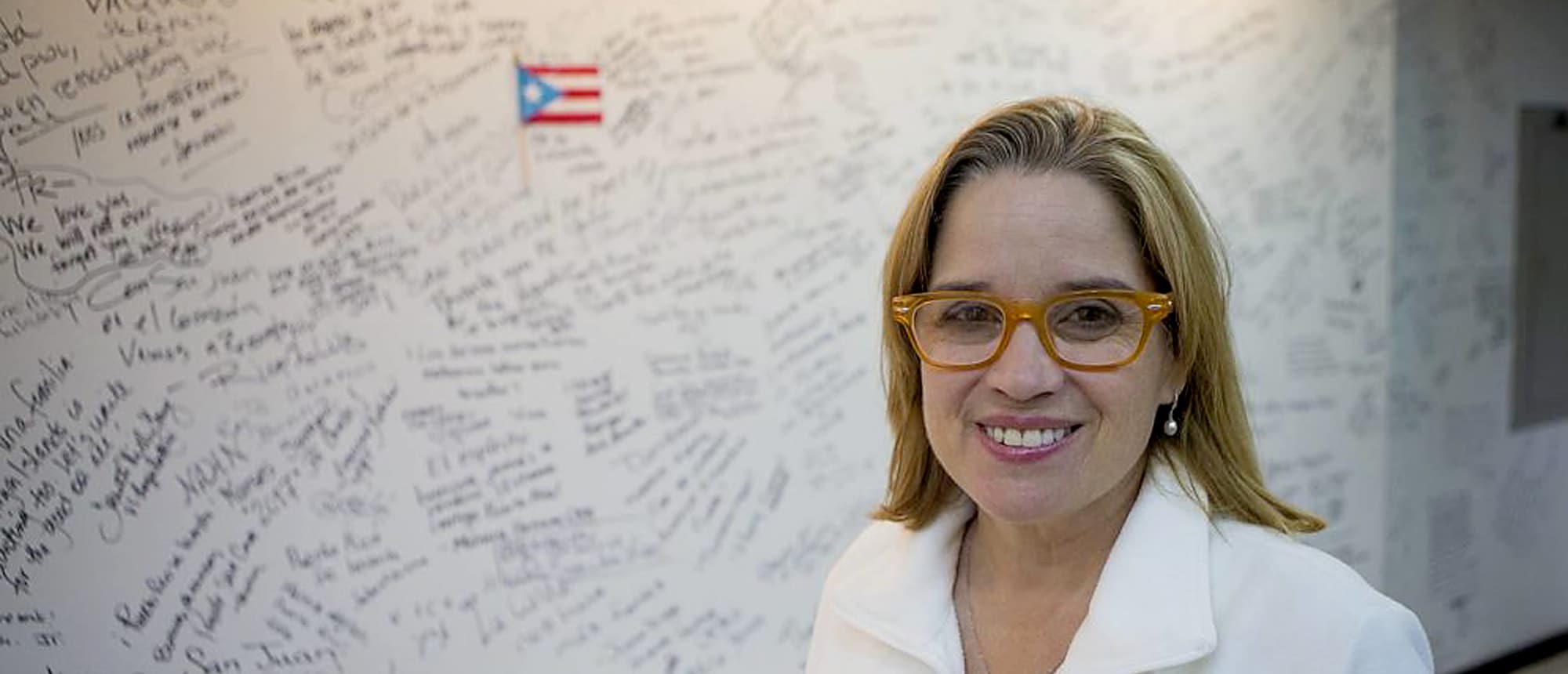

San Juan’s Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz Reflects On One Year Since Hurricane Maria

On Sept. 21, the day after the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Maria, WBUR sat down with Carmen Yulín Cruz, the mayor of San Juan, who became a national figure in the days after the storm.

The mayor’s critics say she’s focused too much of her energy attacking President Trump, while San Juan is still struggling to recover a year later.

Cruz sits outside a makeshift office, in an athletic complex that served as the city’s largest shelter after the storm — and where Cruz herself stayed for more than a month.

In this interview, which has been lightly edited, she reflects on the first anniversary, the death toll and the inability of Puerto Rico to act in its own defense — and on her time in Boston.

Carmen Yulín Cruz:

Yesterday was a day when we gave ourselves permission to grieve.

It was about two weeks ago that the official death toll was raised from 64 to 2,975. Of course, the people that lost loved ones knew, we all knew. Why did the Puerto Rican government wait until three weeks ago to say what everyone knew? FEMA received 2,741 requests for funeral assistance, which is eerily similar to that 2,975. People were dying because they were gasping for air because they were plugged into a respirator, or they didn’t get their nebulizer to treat themselves, or they didn’t get their dialysis in time or chemotherapy in time — [all] because there was no electricity.

And there was a spin from the White House to say this is an “unsung success.” Well, when you have to sing your own praises, it’s because people don’t see it. The response from the federal government was inappropriate, it was inadequate, it was ineffective, it was negligent. And some have gone so far as to say it was a crime.

The U.N. says that whenever people are denied the access to essential services that constitutes a violation to our human rights. The director of [the Puerto Rican electricity authority] said he was told that Puerto Rico could not purchase any generators or electric poles from countries outside of the U.S. — but the U.S. didn’t have any poles left because of the emergencies that happened. The U.S. can buy from other countries, like Colombia, but they weren’t allowing us to buy from Colombia. Our hands are tied, which is why it’s an issue of human rights. We are literally a hostage market.

You’ve become a national figure in the wake of Maria, but how has it affected you personally, everything you’ve been through?

I often say to people that I’m just a small person that spoke very loudly, because the injustice and the unfair treatment of the people of Puerto Rico was evident to everybody. In a humanitarian crisis, you either speak up or you shut up, and if you shut up you become an accomplice to

I have become a lot more centered in terms of what my goals in public service are. One is the eradication of poverty. We can no longer hide our poverty and our inequality behind piña coladas and palm trees. How do we make education continue to be what it can be, the great equalizer? Everything I do now is about making sure people have a safe home. We’ve changed public policy in San Juan so energy is not an afterthought, but an integral part of a resiliency plan for the city. We’ve established that every home that we build or rebuild has to be able to run on solar lights and has to be able to harvest the rain, so people are more [self-sufficient].

I was in Puerto Rico shortly after the storm, and returning a year later the most powerful thing you see is the vegetation is back. But you learn very quickly that all is not normal. Tell me about how San Juan is doing a year after Maria.

I often say to people: “Don’t let the lights in San Juan fool you.” We still have between 2,600 and 3,000 blue [tarp] roofs, so that’s something that we need to take care of as fast as we can, which is why we continue to push on FEMA to do their job.

You must have read the headlines back in January or February: “$1.5 billion for housing in Puerto Rico.” Well just yesterday they signed the agreement. Just yesterday [Housing Secretary] Ben Carson says: “Oh well you know, for an agreement like this, we’ve done it really fast.” Well really? Tell that to the people that have no homes. Tell that to the people whose everyday life is now tainted blue because the sun comes through that tarp — the color of desperation, the color of loneliness, it’s blue.

So that’s one thing. We have tons of bridges that still need to be either rebuilt or mended. We have about 100 traffic lights that belong to the central government that aren’t working.

On the one hand we have that, and on the other hand we’re building 21 centers for community transformation — which is a center [to enable local] people to be first responders. It’s a challenge, but I have no doubt that we’re going to make it.

What about all the people who have left Puerto Rico in the wake of the storm? According to one estimate, 77,000 people still haven’t returned.

A lot of the children left. That happens in areas where there’s been wars. You hear about the children of London being taken away into the countryside [in World War II]. You hear about the children in Cuba that were sent to the United States. Children are taken away because they’re the future, so you want to give them a better life.

The problem is that we have to come back. And I say “we” because 5 million Puerto Ricans are in the states and 3 million Puerto Ricans are in Puerto Rico. We are now the diaspora. But it’s very hard to come back to a place where the basic services are a struggle. And for our children — especially children that have some sort of disability or some sort of a physical or emotional challenge — it’s very difficult. I know people that have decided to send their children and they’re staying here. It’s a devastating loss — it’s like a loss after a loss.

Suicide rates have gone up between 30 to 50 percent; suicide attempts have gone up almost 60 to 75 percent. And you know, people lose hope, so our job is to ensure that they don’t.

And all this comes in the midst of an economic crisis that some economists call Puerto Rico’s “Great Depression.”

First of all, I think it’s a “great exploitation.” Hedge funds, they loaned money to Puerto Rico, money that they know the Puerto Ricans couldn’t pay. They loaned the money for pennies and now they want us to pay them dollars.

And two years ago the Fiscal Management and Control Board was imposed by the Obama administration, which just goes to let you know what colonialism is all about. And the fiscal control board now decides what happens: Pensions get reduced, the [academic] credit at the University of Puerto Rico goes from $54 to $157. It doubles that when you go to a master’s degree. Three-hundred schools were closed in the past two years and about 300 schools were closed before that — so before [Puerto Rico] had 1,600 schools and know you have close to 1,000. You’re talking about the singular [most important] tool to get out of poverty, which is education.

The fiscal control board has to go. They have no place in Puerto Rico.

There’s a lot of [disaster recovery] money that’s going to be coming into Puerto Rico right now. The numbers tell us that $4.5 billion in construction contracts have [already] been granted. Out of that you would think the largest chunk would be for contractors in Puerto Rico — but no, only $500 million of the $4.5 billion. The majority of the money will be sucked out.

You say the reconstruction money will get sucked out, as if it were a foregone conclusion. Is it possible that this money becomes a stimulus to the economy?

Oh, that’s why I continue to speak and speak and speak.

One of the things that Maria did is it shed a light on Puerto Rico, and it allows us the opportunity of a world stage. There are Puerto Ricans that feel themselves as second class citizens. And then there’s the ones like me: I’m a Puerto Rican national that has American citizenship. So I live in a dual relationship. I respect very much the ties of Puerto Rico and the United States have, but right now it’s not a dignified relationship. I don’t want to be a colony. The American people are better than that. They’re hardworking people, people that fought very hard in a place called Boston, which I know very well, precisely to rebuke financial domination. That was what the Boston Tea Party was all about. You don’t get that just because you’re a citizen — you get that because you’re human.

Talk about your connection to Boston.

In 1980 I went to Boston University [to study political science]. It was the first time I left home. Best time of my life. Boston University and Boston itself opened up a new world to me. It was the first time I was exposed to a variety of different cultures. It gave me a different view on life. To me it was the opening of a world of accepting differences rather than tolerating differences. You don’t put down people because they are different. I participated in the rich culture that Boston has to offer.

It’s good to hear nice things about our city. Boston has this reputation as the most racist place in America.

Everyone has lights and shadows — that happens in San Juan, that happens in Puerto Rico, that happens in the best of places. But if you look at Boston, you look at BU, you look at Boston College, you look at Northeastern, you look at Harvard, you look at MIT — a lot of great minds go to Boston to be shaped. I didn’t perceive it as racist. The civil rights movement was a little bit shaped by the city of Boston and by Boston University — Martin Luther King got his doctorate degree there.