Meet The New Boss, Same As The Old Boss

The announcement by the CEO’s from JP Morgan Chase, Amazon and Berkshire-Hathaway that they are forming a new healthcare company signals the symbolic end of the ACA-reform era. They recognize the inefficiencies and profiteering of the private insurance companies, who add no value to businesses dealing with healthcare. And should there be any doubt that the end of the ACA is nigh, there’s this from Trump: “We repealed the core of disastrous Obamacare. The individual mandate is now gone.”

Given the record of the CEO-in-chief who now occupies the White House, it’s doubtful we can expect improved healthcare, or lower costs, under his leadership, which should give us pause before putting CEOs in charge of our health.

If the ACA had fulfilled its promises, a new company by these CEOs would not be needed. The ACA sought to lower costs by forcing consumers to put more “skin in the game,” in Obama’s Budget Director Peter Orzag’s infamous phrase. Yes, patients are spending more, and in 2017 insurance premiums went up over 25% in many areas, deductibles have continued to climb to an average of $1440 for employees in large groups, and drug prices have skyrocketed for long-standing medications like Insulin and newer specialty drugs like Harvoni for Hepatitis C. High-deductible plans and a steady shift so workers pay more for insurance (on average 30% of premiums that are $18,000/year) has not lowered overall costs. Even worse, patients who have paid high premiums are not able to get care because they cannot afford the out-of-pockets costs their expensive insurance does not cover.

Into the breach come the heroic CEOs Bezos, Dimond and Buffett (BDB*). What do they offer? A company that can control costs. How will they do it? With technology, of course. Apparently we have come full circle: since the government regulatory program couldn’t enact effective cost control and utilize technology to save money, let’s have a corporation do so. But it is precisely the industry model that has created our dysfunctional, “money is the metric” approach to health. In the present healthcare industry, the war for revenue between insurers, drug companies, and hospital corporations, along with medical equipment manufacturers and other suppliers, has raised prices and created immense profits. Electronic Medical Records, and other technological innovations are supposed to anchor the new healthcare system. They are expensive, in fact more expensive than any savings they generate. The result of the ACA push to pay for “performance” has been to punish clinicians and hospitals with high-needs patients, no lowering of costs, and increased denials of care since there is an incentive to avoid rather than treat patients who will lower your “performance” score.

Somebody or some entity is going to make the decisions regarding the healthcare we get. Do we really believe CEO’s rather than clinicians should make those decisions? If the decisions are based on corporate bottom lines we can expect continued cost shifts to workers, deployment of labor-displacing technologies with unproven impacts on patient care quality, and fragmentation as each corporate castle fortifies its strategic market position: Aetna-CVS will go toe-toe-toe with BDB* as the Ascension hospital corporation (nation’s largest) pushes back, for example. Since less care equals greater profits, and more covered lives means greater revenue, we can see that money will likely remain the metric.

Those who control capital, like the richest guy in the world, investment banks and investors, favor capital-intensive approaches to social problems. Technology fits that bill. Yet, technology only serves the purposes for which it is designed: it is neither socially neutral nor a panacea. Nurses know, however, that human health cannot be reduced to an algorithm, subject as it is to the particularities of an individual’s family history, environment and most fundamentally, socio-economic status. Let’s hope the technologists and CEOs quickly learn from direct care RNs. Standardization of treatments whether through algorithms, protocols, or budget-mandates do not match the needs of individual patients.

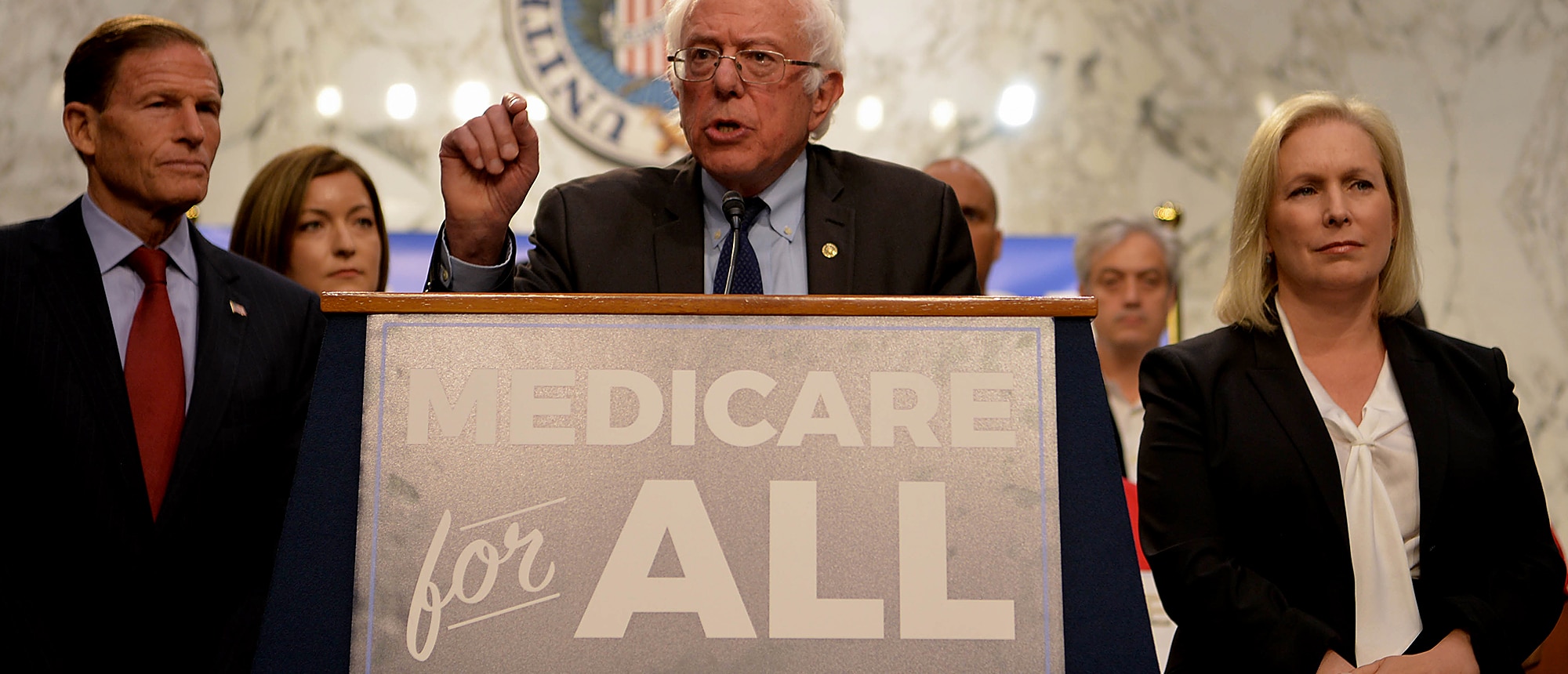

Alternatively, the US could expand and improve the current program that puts clinicians in charge, is popular, and works at controlling costs: Medicare. With administrative costs as low as 5–6% compared to the 13% or higher for private insurance, Medicare is more efficient. The growth in Medicare spending, around 2.4% annually, is much less than growth in overall healthcare spending and far less than recent premium increases. Under Improved Medicare for All, benefits would be expanded to include those that ACA, Medicaid and CHIP provide, and Medicare will negotiate prescription drug prices. The biggest shortfalls in Medicare, the escalating privatization pushed by the insurance-financed politicians that have resulted in higher out of pocket costs for seniors, over payments to the private Medicare Advantage plans and the “donut hole” in the private the prescription drug benefit, would be eliminated through a robust Medicare for all plan, such as proposed nationally in Sen. Bernie Sanders S 1804 bill or the California single payer bill SB 562.

Moreover, traditional Medicare enables physicians to deliver the care their patients need without onerous “gate-keeping,” prior authorizations or narrow networks that insurers use to restrict access, limit choice of providers and undermine the clinical judgment of doctors and nurses. In fact, since older Americans tend to be the most intensive users of health services, expanding the pool by including everybody especially low-needs patients will make the program more sustainable.

Should patients, workers and employers be on the hook for the excessive compensation and enormous profits of the health insurance industry? In California between 2011–16, insurers made $27 billion in profits/net income. Why should we subsidize the failed business model of health insurers? (Employers get $342 billion each year in tax subsidies to lessen the cost to them of private health insurance.)

On this BDB is right—health insurance companies add no value, and the profits in healthcare are obscene. That recognition matters and can point the way toward real reform. The solution is not more of the same. We must contain prices in order to control costs. An industry approach cannot do that and also place patient care at the center of a reformed system.