The West’s Broken Promises On Education Aid

The Global Partnership for Education, a worthy and capable initiative to promote education in 65 low-income countries, is begging for funds. The fact that it must do so – and for a paltry $1 billion per year, at that – exposes the charade of the US and European commitment to education for all.

The Global Partnership for Education, a worthy and capable initiative to promote education in 65 low-income countries, is having what the jargon of development assistance calls a “replenishment round,” meaning that it is asking donor governments to refill its coffers. Yet the fact that the GPE is begging for mere crumbs – a mere $1 billion per year – exposes the charade of Western governments’ commitment to the global Education for All agenda.

The United States and the European Union have never cared that much about that agenda. When it comes to disease, they have at times been willing to invest to slow or stop epidemics like AIDS, malaria, and Ebola, both to save lives and to prevent the diseases from coming to their own countries. But when it comes to education, many countries in the West are more interested in building walls and detention camps than schools.

The GPE does excellent work promoting primary education around the world. Donor countries, all of which long ago signed on to Education for All, should be clamoring to help one of the world’s most effective organizations to achieve that goal. Yet generous donors are few and far between.

This reality extends back to imperial times. When most of Africa and much of Asia were under European rule, the colonizers invested little in basic education. As late as 1950, according to United Nations data, illiteracy was pervasive in Europe’s African and Asian colonies. At the time of independence from Britain, India’s illiteracy rate stood at 80-85%, roughly the same as Indonesia’s illiteracy rate at the time of independence from the Netherlands. In French West Africa, the illiteracy rate in 1950 stood at 95-99%.

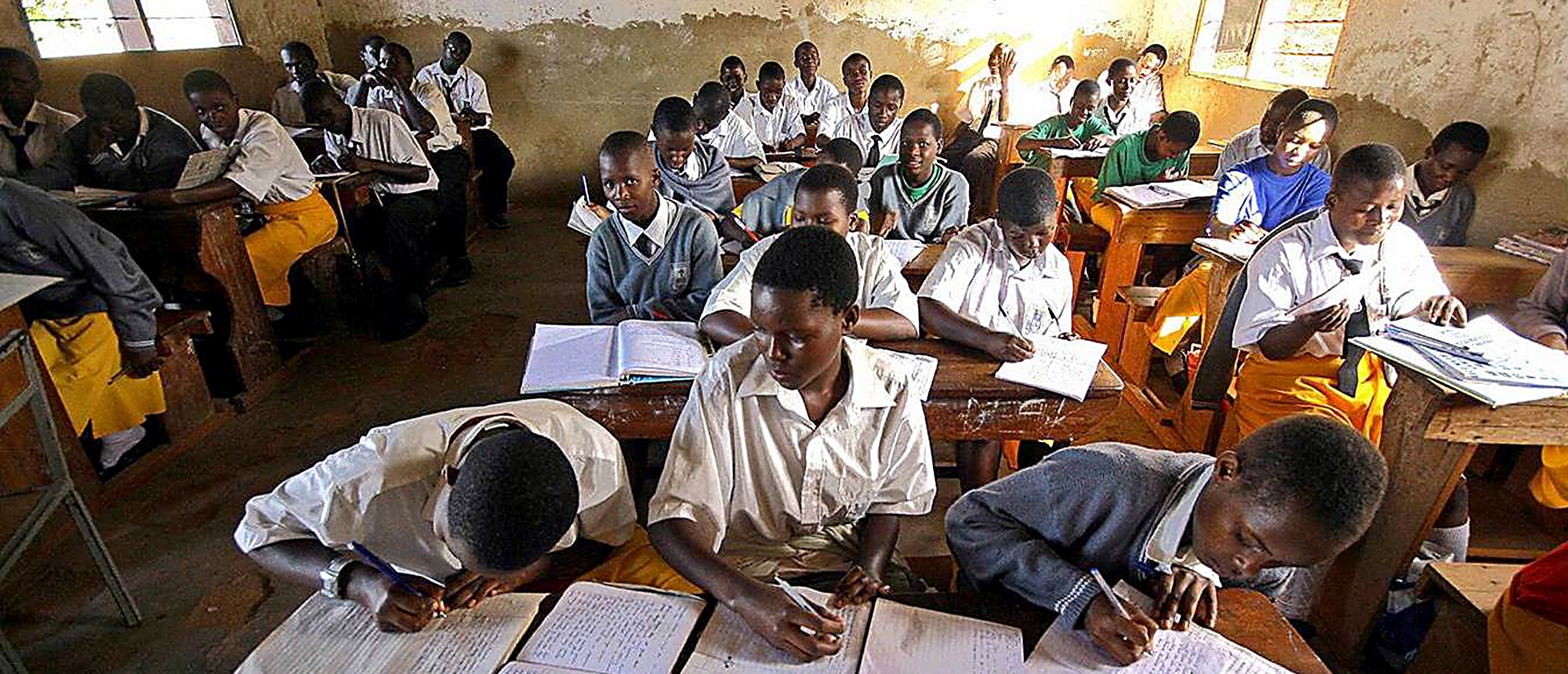

After independence, African and Asian countries pursued massive and largely successful initiatives to raise basic education and literacy. Yet, far from seizing this opportunity to make up for lost time, Europe and the US have provided consistently meager assistance for primary and secondary education, even as they have made high-profile commitments such as Education for All and Sustainable Development Goal 4, which calls for universal access to pre-primary through secondary school.

Consider the grim data on development aid for education, which has stagnated for years – and actually declined between 2010 and 2015. According to the most recent OECD data, total donor aid for primary and secondary education in Africa amounted to just $1.3 billion in 2016. To put that figure in perspective, the US Pentagon budget is roughly $2 billion per day. With around 420 million African kids of school age, total aid amounted to roughly $3 per child per year.

It’s not as if Western governments don’t know that far more is needed. Several detailed recent calculations provide credible estimates of how much external financing developing countries will need to achieve SDG 4. A UNESCO study puts the total at $39.5 billion per year. A report by the International Commission on Financing Education Opportunity, led by former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown, similarly put developing countries’ external financing needs at tens of billions of dollars per year.

Here is the reason why aid is needed. A year of education in Africa requires at least $300 per student. (Note that the rich countries spend several thousand dollars per student per year.) With Africa’s school-age population accounting for roughly one-third of the total, the per capita financing requirement is about $100. Yet for a typical African country, that’s about 10% of per capita national income – far more than the education budget can cover. External aid can and should cover the financing gap so that all children can attend school.

That’s not happening. Annual spending per school-aged child in Sub-Saharan Africa is roughly one-third of the minimum needed. As a result, most kids don’t come anywhere close to finishing secondary school. They are forced to drop out early, because there are no openings in public schools and tuition for private school is far too high for most families. Girls are especially likely to leave school early, though parents know that all of their children need and deserve a quality education.

Without the skills that a secondary education provides, the children who leave school early are condemned to poverty. Many eventually try to migrate to Europe in desperate search of a livelihood. Some drown on the way; others are caught by European patrols and returned to Africa.

So now comes the GPE’s replenishment round, scheduled for early February in Senegal. The GPE should be receiving at least $10 billion a year (about four days’ military spending by the NATO countries) to put Africa on a path toward universal secondary education. Instead, the GPE is reportedly still begging donors for less than $1 billion per year to cover GPE programs all over the world. Instead of actually solving the education crisis, rich-country leaders go from speech to speech, meeting to meeting, proclaiming their ardent love of education for all.

Across Africa, political, religious, and civil-society leaders are doing what they can. Ghana has recently announced free upper-secondary education for all, setting the pace for the continent. As African countries struggle to fund their ambitious commitments, new partners, including private companies and high-net-worth individuals, should step forward to help them. Traditional donors, for their part, have decades of lost time to make up for. The quest for education will not be stopped, but history will judge harshly those who turn their backs on children in need.