What Stands In The Way Of Making The Climate A Priority

Inertia and vested interest, it seems to me, are the two forces that make changing the system for the better so rare. Once things are as they are, some group benefits from them—and that group usually has more of a stake in maintaining the status quo than others have in changing it.

But, as I wrote last week, moments arise when the Zeitgeist is threatened—when what is considered normal, natural, and obvious seems suddenly up for grabs. Right now, traditional policing seems less obvious than it did a month ago, and, though the police unions and the administrators will work hard to make that thought disappear, at least for the moment, the discipline and the passion of the people marching and organizing are actually overcoming the tendency for the focus to drift away. And, as a result, all of a sudden the rest of us notice that a few people have been hard at work all along, imagining why it might not make sense to send combat-ready troops into our cities to deal with the slight but inevitable tensions of living together in a society. Here, for instance, is a series of interviews on CNN about how one might deal with speeders or drunk drivers without tickets or arrests. When you first listen, you think, That’s different—would it really work? But that’s the good thing about moments like this: our minds are open to new possibilities in ways that they usually aren’t.

Inertia and interest are the main reasons our energy systems have been slow to change, even though rapid climate change represents the ultimate in imaginable violence, injustice, and chaos. (Indeed, the evidence shows that, around the world, emissions are “surging” back to typical levels as societies emerge from the post-sheltering phase of the coronavirus pandemic.) Sometimes, the efforts of vested interests are almost comical. Consider, for instance, the fact that many of our homes have a large tank of flammable gas that we burn when we wish to heat our food, resulting not only in global warming but also in levels of indoor air pollution that are often so high they would be illegal were they outside. At some point in our history, this was perhaps an improvement over burning wood or dung. But now we have easy-to-use and more affordable induction cooktops, which make far more sense (at least in new homes, where there’s no sunk investment in cooktops and ranges). Some jurisdictions have started mandating the installation of such electric appliances in new construction, threatening the power of the incumbent inflammable technology. I’ve written in this column before of the California gas-workers’ union that, as the journalist Sammy Roth discovered, threatened a “no-social-distancing” protest in a town, at the height of the pandemic, in an effort to block such a law. Now Rebecca Leber, writing in Mother Jones, reports that the natural-gas industry is systematically paying Instagram influencers to plug its product with a targeted audience of “hispanic millennials,” “design enthusiasts,” “promising families,” and “young city solos.”

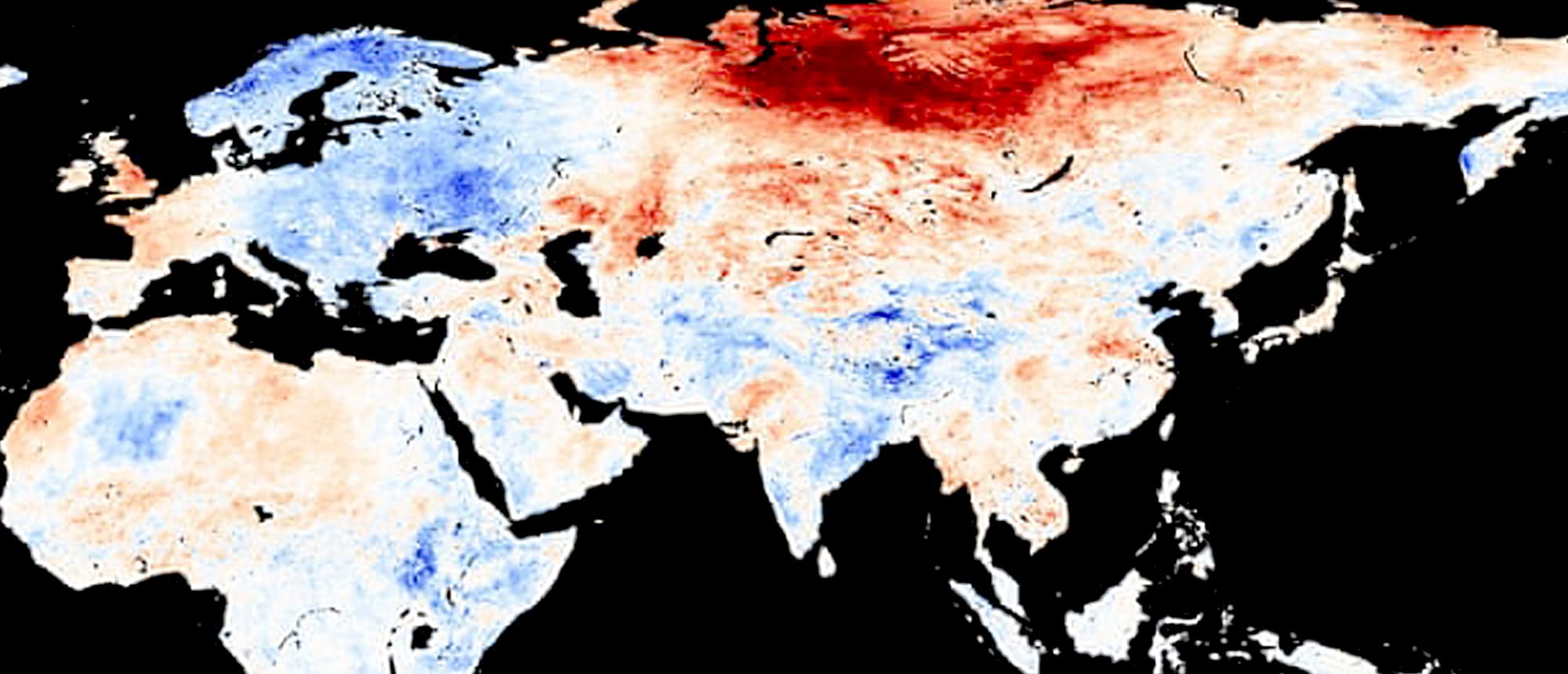

But inertia plays as large a role as interest, sometimes. A couple of weeks ago, the Washington Post ran an excellent account of the effort to make the Empire State Building more energy efficient. Aided by gurus from the Rocky Mountain Institute, who have been working on such projects for decades, the management changed out old lights, added insulating film to the building’s sixty-five hundred windows, stuck reflecting foil behind the radiators, and provided “regenerative braking” for the building’s seventy-three elevators, so that, when they slow down, the extra electricity is returned to batteries. These and other changes reduced the building’s electricity use not by five or ten per cent but by forty per cent. Forty is a big number, considering that the tenants still get the same use from their offices, which are as well lit, warmed, cooled, and ventilated as before. We obviously have to install a lot of solar panels and wind turbines in the next decade to meet climate goals, but if we cut electricity use by forty per cent we’d have to install far fewer. That we haven’t done so is, I think, mostly a function of that inertia. If you’re running a building, you have many jobs: finding tenants, collecting and raising rents, providing basic services and maintenance. And business school might not have taught you about regenerative braking. But now you may have to learn: last week, the Times reported that even institutions as sacred as the thirty-year mortgage are under threat, as banks start figuring out they don’t want to be left holding properties that are literally underwater. As the great poet James Russell Lowell once observed, “New occasions teach new duties.” The past seven years have been the hottest ever recorded, and, on Saturday, a spot on the Siberian coast became the northernmost place on Earth to record a temperature of a hundred degrees Fahrenheit; this is a new occasion.

Passing the Mic

R. L. Miller is a California climate activist who, for some years, has run a PAC called Climate Hawks Vote, which tries to elect candidates who are particularly eager to combat global warming. (I’ve sat on the board of the group.) She has also served as chair of the climate caucus in the California Democratic Party, and has just been elected by fellow California Party members to the Democratic National Committee, with the goal of making the climate a priority in the campaign.

What’s the strategy for the D.N.C.?

Top priority right now is the platform! I ran for the D.N.C. on a platform of transparency and accountability. I was particularly fired up about the D.N.C. leadership’s refusal to hold a climate debate.

The D.N.C. Climate Council has released a bold, visionary set of policy recommendations. I helped set up the council, and am on its advisory board, but can’t take credit for drafting the recommendations. Check out the platform!

Separately, the Biden-Sanders unity task forces are finishing up their work and are due to release their recommendations soon. I don’t know whether those recommendations will play into the platform. Everything has been done behind closed doors, and I’ve heard rumors that the recommendations may not be made public. Having said that, there are some very good people on the climate task force, whom I trust to convey the urgency of the climate crisis.

Finally, there’s the official platform-drafting committee of the D.N.C. Apparently, the Climate Council’s work has offended some old-school types at the D.N.C. To be clear, I’ve been elected to the insurgent wing of the D.N.C.! If the official platform committee is doing anything at all, besides sniffing at insurgents, it’s not happening in public. So I believe the D.N.C. needs to be holding public hearings on the platform.

Poll after poll during primary season showed climate change was the top priority for young voters, and second only to health care for Democratic voters in general. Do you sense that the Party is ready to make it a priority, too? What stands in the way?

What stands in the way of making climate a priority is a lot of old-school Democrats—some in trade-union labor and some just plain establishment folk—who think that bold climate action will cost us key states. And they’re badly missing the point. Poll after poll after poll shows that the American people are hungry for bold climate action. People generally see the enormous job potential of a hundred-per-cent clean-energy transition.

And then there’s the scary part. What I’ll be taking to the D.N.C. is a very personal perspective on a climate-fuelled disaster. The Woolsey Fire, of November, 2018, came within five hundred feet of my home. I heard about it early enough, via Twitter, that I was able to evacuate my frail, elderly mother safely. I watched my children’s childhood memories burn down on national television: their preschool, their soccer fields, their neighborhood parks. I remain nervous and jumpy every October, when the hot Santa Ana winds blow. I don’t know if anyone else on the D.N.C. can say they’ve been directly affected by a climate disaster. But it changes one’s perspective.

You keep track of lots of congressional and local races around the country. Who are the candidates you’re watching most fondly?

Everyone who’s not focussed on the Presidential race is working hard on flipping the Senate. At Climate Hawks Vote, we’ve endorsed Mark Kelly, in Arizona, and Jaime Harrison, in South Carolina, both of whom were unopposed in their primaries. We stand with every other green group in the nation for Ed Markey, of Massachusetts, the co-author of the Green New Deal and countless other climate bills.

Probably the best race from a climate perspective is the Colorado Senate primary, on June 30th. Andrew Romanoff is running explicitly on a Green New Deal, and his initial climate ad went viral. Washington Democrats prefer John Hickenlooper, known unfondly as Frackenlooper. Romanoff has recently gained ground on Hickenlooper in the polls.

At the same time, there’s room for more real climate hawks in the House. Too many Democrats, still, pay lip service to the climate crisis, but witness how rank-and-file members of Congress have had to beg leadership for crumbs of clean-energy tax-credit extensions. We’ve endorsed Cathy Kunkel—yes, there are climate hawks in West Virginia—and Christy Smith, in California, and are planning more endorsements.

[I should note, for the record, that I’ve done events with the Kunkel and Romanoff campaigns as well.]

Climate School

Speaking of bracing challenges to business as usual, the invaluable Kate Aronoff offers an update on New York City activists’ plans to turn the fetid penal colony on Rikers Island into a solar farm. A quarter of the island’s real estate could provide enough energy to turn off the gas “peaker” plants scattered around the city, many of them in the communities housing the people of color who, at the moment, end up on Rikers in disproportionate numbers. An alternate plan? Another runway for LaGuardia, which would pretty much define business as usual.

A warming climate causes sharp increases in stillbirths and low-birth-weight babies, according to a new study. During the hot months of the year, a one-degree-Celsius increase in temperature in the week before delivery raised the chances of stillbirth six per cent, and—per usual—the effect was worse for black mothers. “Black moms matter,” one of the study’s authors said. “It’s time to really be paying attention to groups that are the most vulnerable.”

There has been some alarm in the climate-science community these past weeks over a new study suggesting that the planet’s temperature may rise even faster than feared. According to this new research, clouds seem to exacerbate warming, so the damage from doubling carbon dioxide in the atmosphere may be a rise of five degrees Celsius, not three. There has been some pushback, too, from climate experts such as nasa’s Gavin Schmidt, who argues that the consensus figures are probably more likely to be accurate, and that any reëvaluation is at best “premature.” It seems to me that this debate overshadows the more important growing sense that any given temperature rise produces more ecological havoc than scientists predicted. With global temperatures up just one degree, for instance, we have seen a hellish heat wave across Siberia. A sobering account in the Guardian reports that, among other things, “swarms of the Siberian silk moth, whose larvae eat at conifer trees, have grown rapidly in the rising temperatures.” A moth expert named Vladimir Soldatov told a reporter, “In all my long career, I’ve never seen moths so huge and growing so quickly.”

“Everywhere I have been—inside BP, as well as outside—I have come away with one inescapable conclusion,” Bernard Looney, the C.E.O. of the British oil giant, said in a speech in February. “We have got to change.” Maybe the company is set on shifting, as the Times reported last week, but Amy Westervelt—whose Drilled blog is an endless source of good information—got her hands on a video of Looney talking to his own troops. “We’re probably going to be in oil and gas for decades to come,” he says, “because how else is that eight-billion-dollar dividend going to get serviced?”

An interesting examination by Ted Nordhaus and Seaver Wang of the reasons that some East Asian countries may be turning away from nuclear energy proposes that the trend may be less because of the technology and more because of nuclear power’s historical ties to regimes now out of favor.

The Irish government seems close to becoming a world climate leader: if the various parties agree, a new “programme for government” would not only mandate seven-per-cent annual emissions cuts but would also stop all new exploration for oil and gas in Irish waters, and would ban the importation of fracked gas from the United States. (Though there’s always a local angle: the proposal doesn’t put a solid end date on the practice of burning peat.)

In the United Kingdom, the veteran campaigner Jonathon Porritt, whose activism stretches back to the nineteen-eighties, has a new book out, “Hope in Hell,” which argues that this could be the “climate decade”—but only if we summon “a sense of intergenerational solidarity as older generations come to understand their own obligation to secure a safer world for their children and grandchildren.”

Scoreboard

A rather large win this past week: the Vatican Catholics to divest from fossil-fuel companies—indeed, to “shun” them. The Vatican Bank said that it is following this advice.

Warming Up

If there’s one thing this newsletter appreciates, it’s good organizing, especially when no one sees it coming. Apparently, K-pop stans played no small role in persuading the Trump campaign that massive crowds of true believers were heading for its Tulsa kickoff rally, instead of the less-than-sell-out number that actually showed up. I think BTS would almost certainly sell out the B.O.K. Center, and with luck they’d perform “Not Today.”

“You want a new world, too? Oh, baby, yes I want it.”