Who Pays If We Raise The Social Security Payroll Tax Cap?

Most Americans know that their earnings are subject to the Social Security payroll tax. Not as many are aware that the amount of earnings subject to the tax, while subject to change, is capped at the same level for everyone, regardless of total earnings. This year, the maximum wage earnings subject to the payroll tax is $127,200.

The cap on the Social Security payroll tax means that those with the highest earnings pay a lower rate. People who earn a million dollars a year pay this tax on about an eighth of their earnings. People who earn a quarter of a million dollars pay the tax on just over half of their earnings. It is important to note that this just applies to wage earnings, not other forms of income. If an individual earning $250,000 a year makes another $250,000 from investments, then they end up paying the Social Security income tax on about a fourth of their income. The vast majority of workers fall below the $127,200 cap and have significantly less stock or other income, if any. As a result, all — or the majority — of their income is typically subject to the payroll tax.

The Social Security payroll tax essentially finances what is commonly called Social Security, the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program (OASDI). The contributions from the tax (6.2 percent paid by employees and employers, 12.4 percent by the self-employed) are held by the Social Security Trust Fund as Treasury bonds and are the source of Social Security benefits for retirees.

The latest Social Security Trustees report showed the Trust Fund at $2.8 trillion. This is enough to pay full benefits to retirees through 2034. At that point, the fund will still be able to pay just under 80 percent of full benefits for the next 75 years. Over this period of time, the gap between full benefits and payable benefits comes out to roughly one percent of GDP over this period.

There are a number of ways this gap can be eliminated to not only ensure that full benefits are paid beyond 2034, but expanded to provide additional retirement security for millions of workers. Proposals to raise or totally eliminate the payroll tax cap would have a significant impact on benefit payments and the program’s projected shortfall after 2034. Such proposals ensure that high-income earners pay as much, or closer to, the same rate as everyone else, thus addressing the regressive nature of the tax.

Raising the cap also addresses the impact of rising wage inequality on financing Social Security benefits. While wages for the top 1 percent of wage earners have continued to grow at a strong pace over the past few decades, they have slowed considerably for low- and moderate-income earners.4 As of 2013, this rising inequality in earnings was responsible for 43.5 percent5 of the projected 75- year shortfall in Social Security funding.

A number of bills were authored in the 114th Congress to shore up and strengthen Social Security —several looked, at least in part, at the Social Security payroll tax cap. Senator Bernie Sanders authored legislation similar to a bill he introduced the previous year and featured it in his 2016 presidential campaign platform that would have applied the payroll tax cap to earnings above $250,000. According to an analysis from the Social Security office of the Chief Actuary, this would have eliminated 80 percent of the projected Trust Fund shortfall. Other legislation by Senator Richard Blumenthal and Representative John Larson would have lifted the cap for those earning more than $400,000. Another bill, sponsored by Senator Patty Murray, would have imposed a 2.0 percent surtax on employers and employees if the employee’s earnings were above $400,000 and a surtax of 4.0 percent if an individual were self-employed.

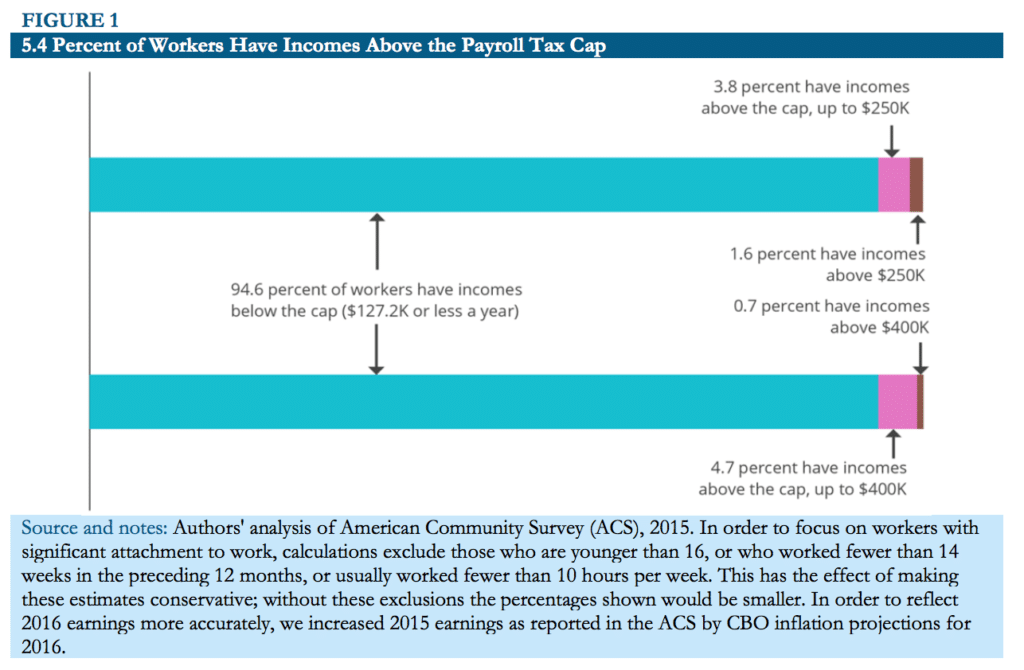

Using Census Bureau data from the latest American Community Survey (ACS), this issue brief updates previous CEPR research to determine how many people would be affected if the payroll tax cap were raised or eliminated. Based on this data, the vast majority of workers would not be impacted. Roughly 1 in 18 people, or 5.4 percent of workers, earn more than the current cap and would be affected if it were eliminated (Figure 1). If workers who earn over $250,000 in wages paid the tax, the top 1.6 percent of workers would be affected. If the cap applied to people who earn over $400,000 in wages, only the top 0.7 percent would be affected.

The effects of eliminating or raising the Social Security payroll tax cap vary widely when looking at race, gender, age, and state of residence. For instance, about 1 in 53 black and Latino workers would pay more if the cap were completely scrapped. A little more than 1 in 35 women would pay additional taxes if the cap were eliminated.