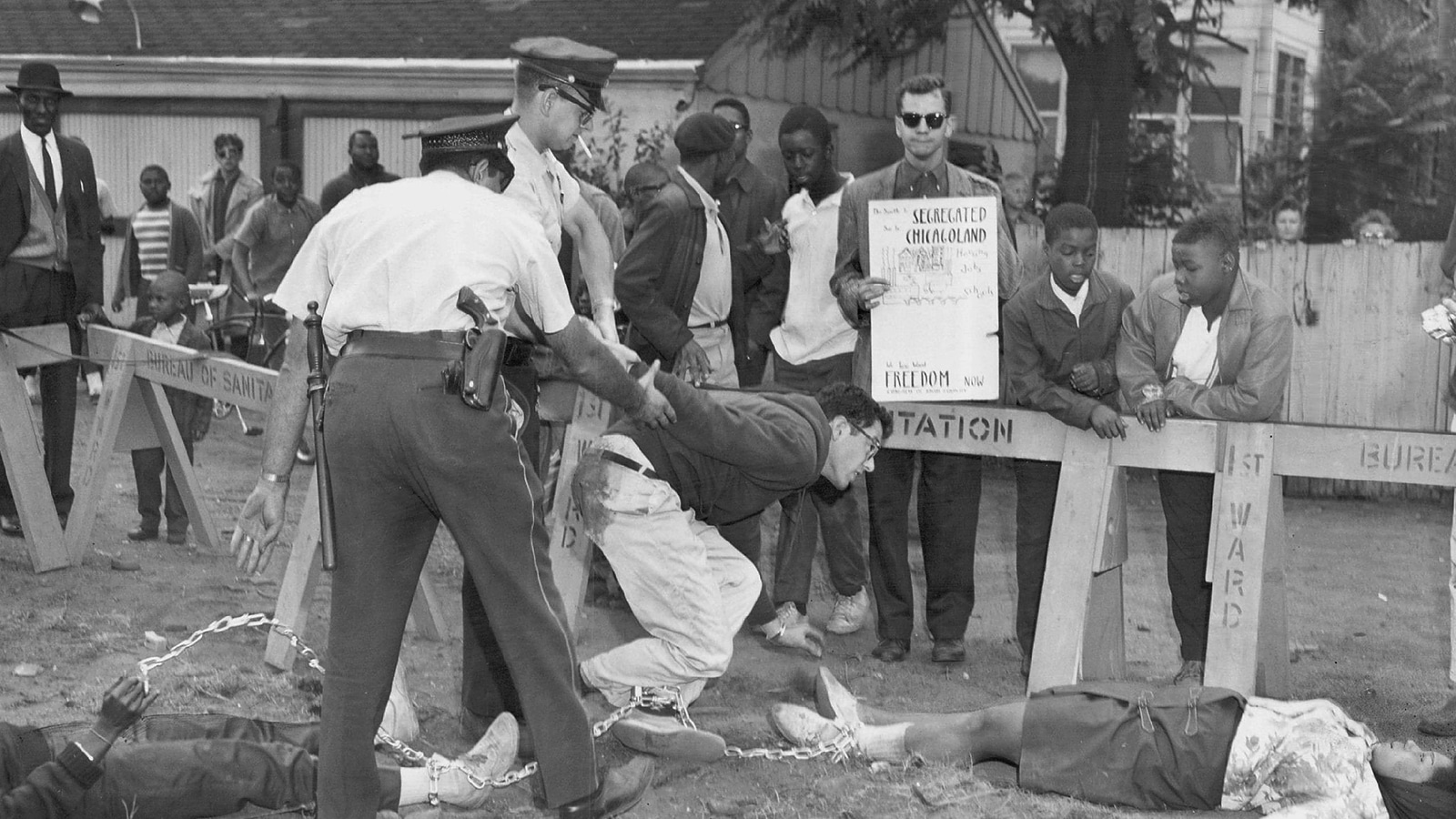

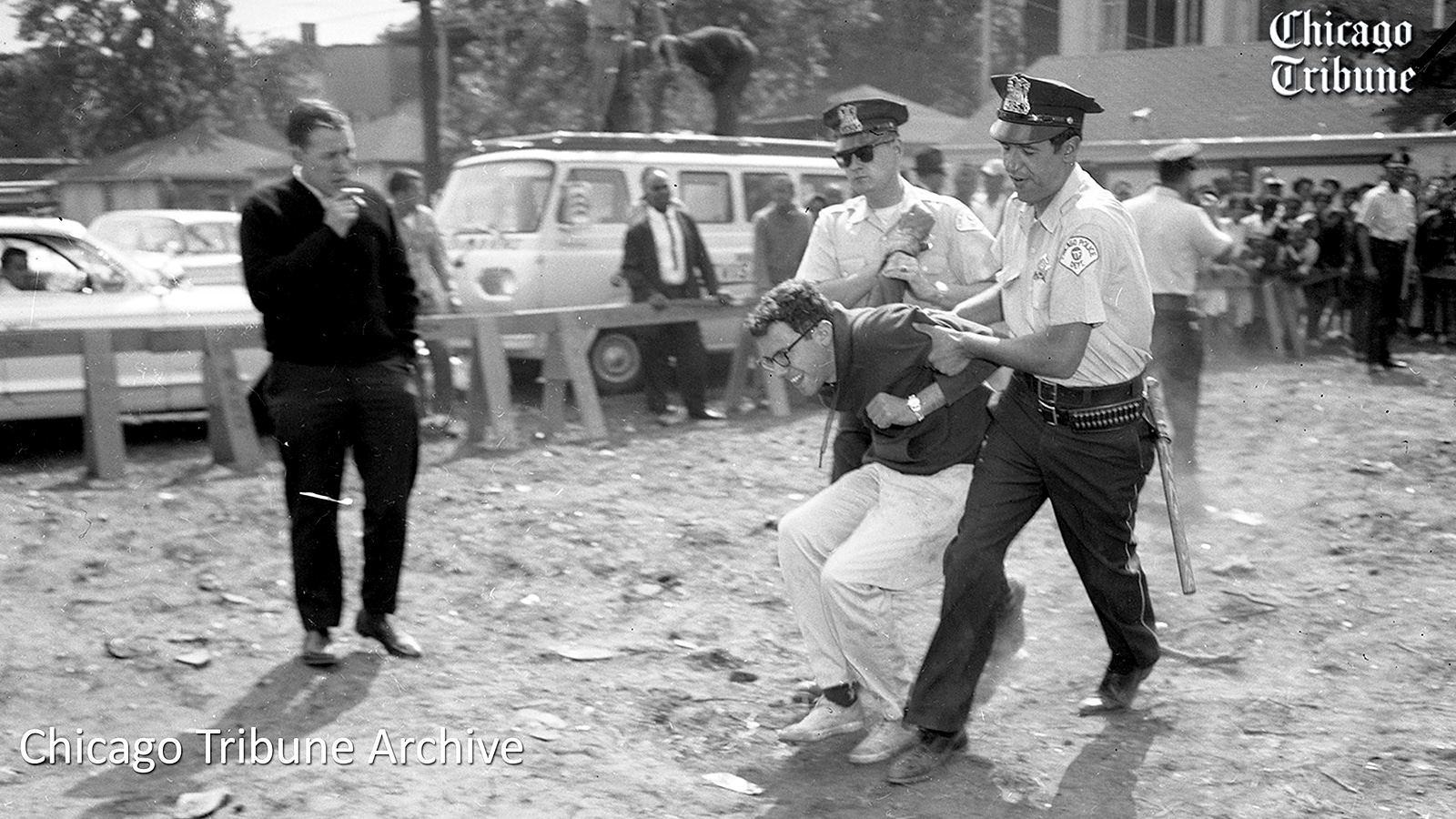

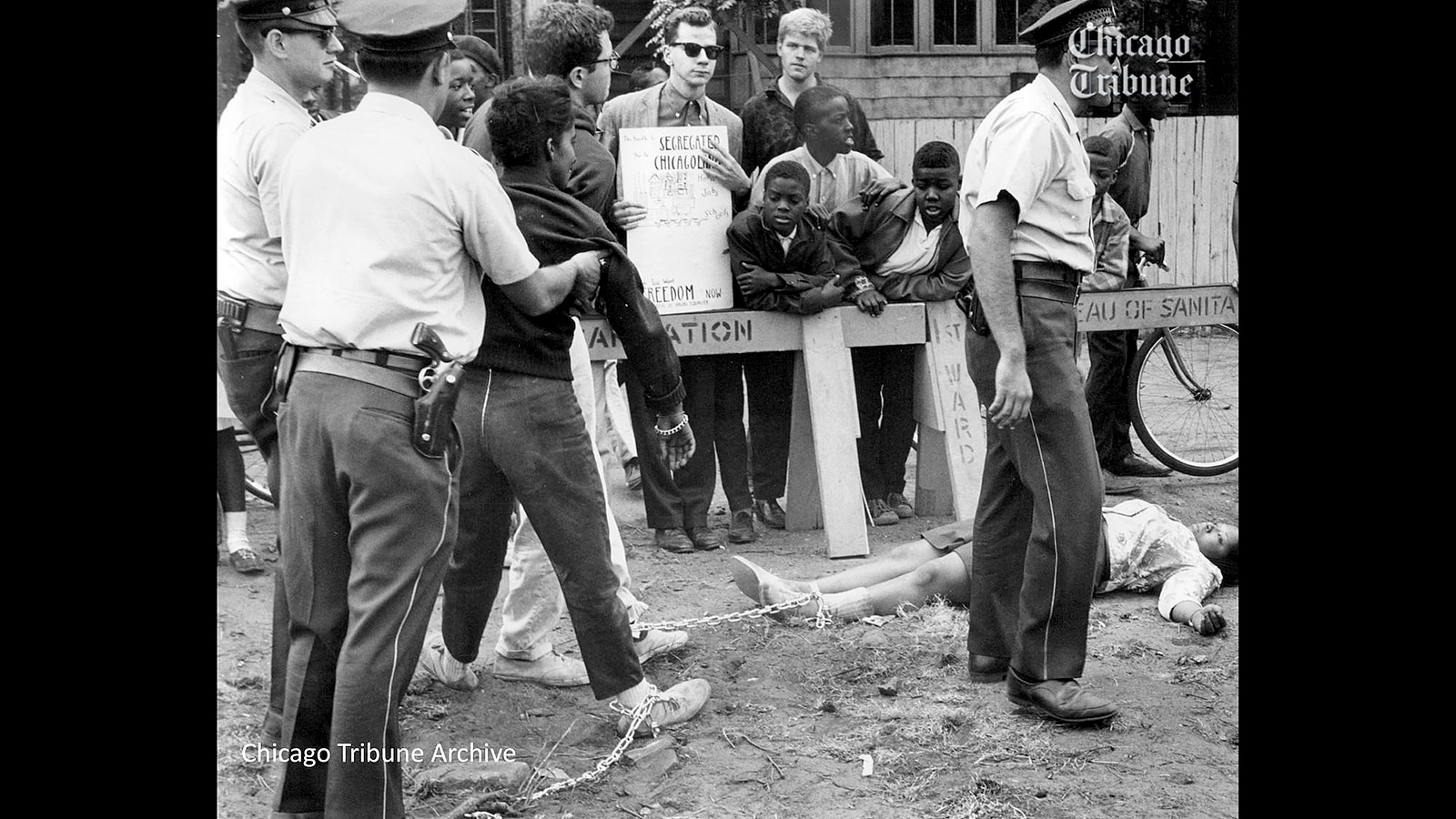

On August 12, 1963, Bernie was charged with resisting arrest for his role in Chicago protests against the use of “Willis Wagons.” He was found guilty and paid a fine of $25.

The “Willis Wagons” were named for Chicago Public Schools superintendent Benjamin Willis. He was despised in the Black community for deploying the wagons (trailers) to school parking lots and playgrounds on Chicago’s South and West sides as overflow space for Black students. The Black community called attention to the fact that the trailers were in place to keep Black students out of white schools – some of which were underpopulated. The racial segregation and inequality boycott saw over 200,000 students, primarily Black, stay home from school.

The ’63 protest in which he participated was part of a decade of civil-rights activism designed to force Chicago to address school segregation in the city. The demonstrations escalated in 1963 and included a massive “Freedom Day” school boycott organized by the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO), a civil-rights coalition including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Urban League, Black and White parents, and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the organization with which Sanders was affiliated.[1]

(Bernie’s) arrest is a window into the civil rights movement in the North and highlights a little-known turning point in the history of civil rights and education equality. The fights over segregation in Chicago are not as well known as the battles in Little Rock or Selma. In the mid-1960s, Chicago became the most important test case for implementing civil-rights legislation prohibiting school segregation.[1]

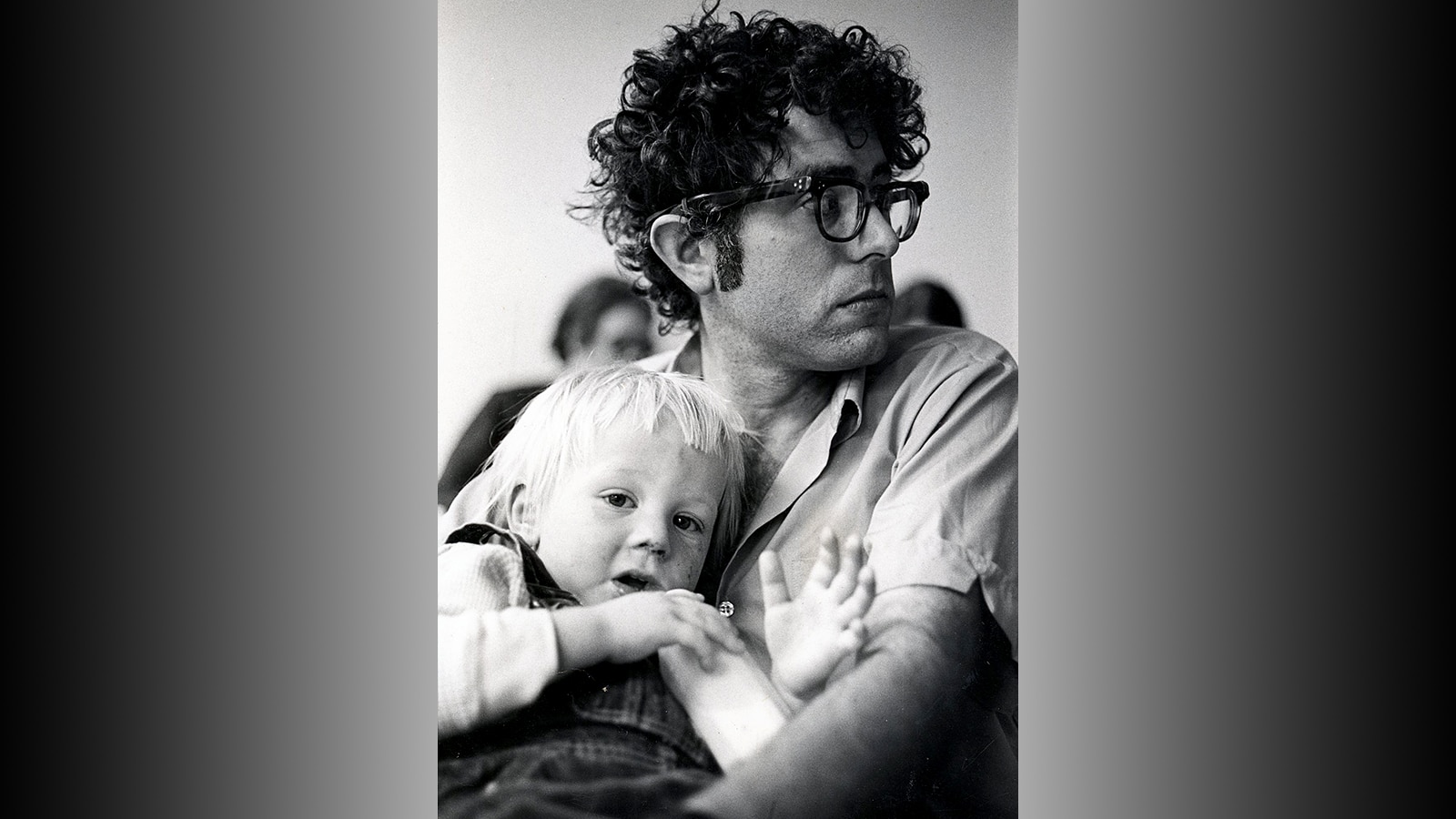

Gordon Quinn, founder of Kartemquin Films, the studio best known for “Hoop Dreams” (1994), (filmed) the protests while a student at the University of Chicago. He turned the resulting footage into the 2017 documentary “’63 Boycott.” The film connects the forgotten story of one of the largest Northern civil rights demonstrations to contemporary issues around race, education, and youth activism.[2]

When asked about Bernie’s role in civil rights during the 2016 presidential campaign, Quinn noted, “One hundred and sixty-nine people had been arrested in the summer of ’63, and four people were charged, and one of them was Bernard Sanders…For a lot of people, Bernie is a tough sell. Not for us. He’s saying all the things we believe in.”[1] Expressing appreciation that voters were debating the civil-rights records of 2016 candidates, Quinn said that “more people now recognize that civil-rights activists were organized, creative, and persistent in the North as well as the South. More importantly, the history of civil rights and school segregation in Chicago, of which Sanders’s 1963 arrest is a part, makes it clear how far America must still travel to achieve equality.”[1]

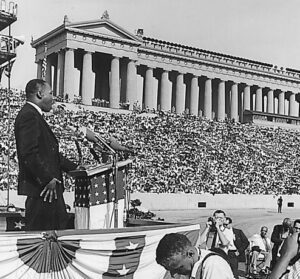

When Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Chicago a few years after the ’63 protests, he responded to a young radio caller who questioned whether her participation in the demonstrations and subsequent arrest had even made a difference because she could not see it.

When Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Chicago a few years after the ’63 protests, he responded to a young radio caller who questioned whether her participation in the demonstrations and subsequent arrest had even made a difference because she could not see it.

Dr. King replied:

“The movement itself created an atmosphere which finally led to the removal of Mr. Willis. So that in itself was an accomplishment. Often you are accomplishing much more than you can see at the moment because you are in the heart of the situation. But those of us who were not here last summer and who happen to be here now see that a great deal was accomplished. And many of the things we are able to do now…(are) because the atmosphere was created last summer for the building of a vibrant movement to end discrimination, injustice, slums… in the city of Chicago.”[3]

Back to Timeline

Back to Timeline