In 1988, Burlington, Vermont, was deemed “one of the most livable (American) cities for the arts.” That distinction came as Bernie Sanders’ began his fourth term as Mayor, as a direct result of his commitment to supporting music and the performing arts throughout his tenure.

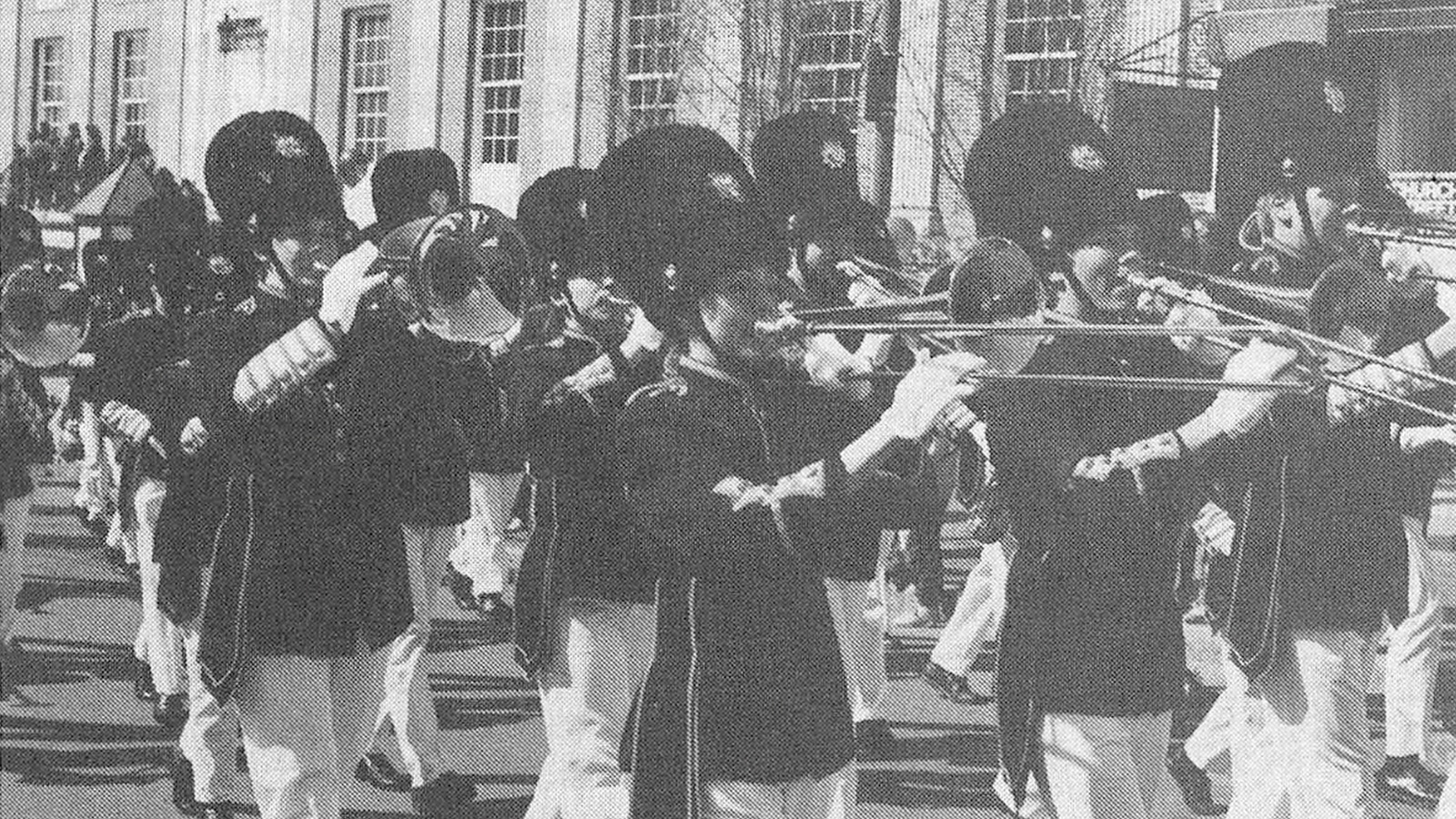

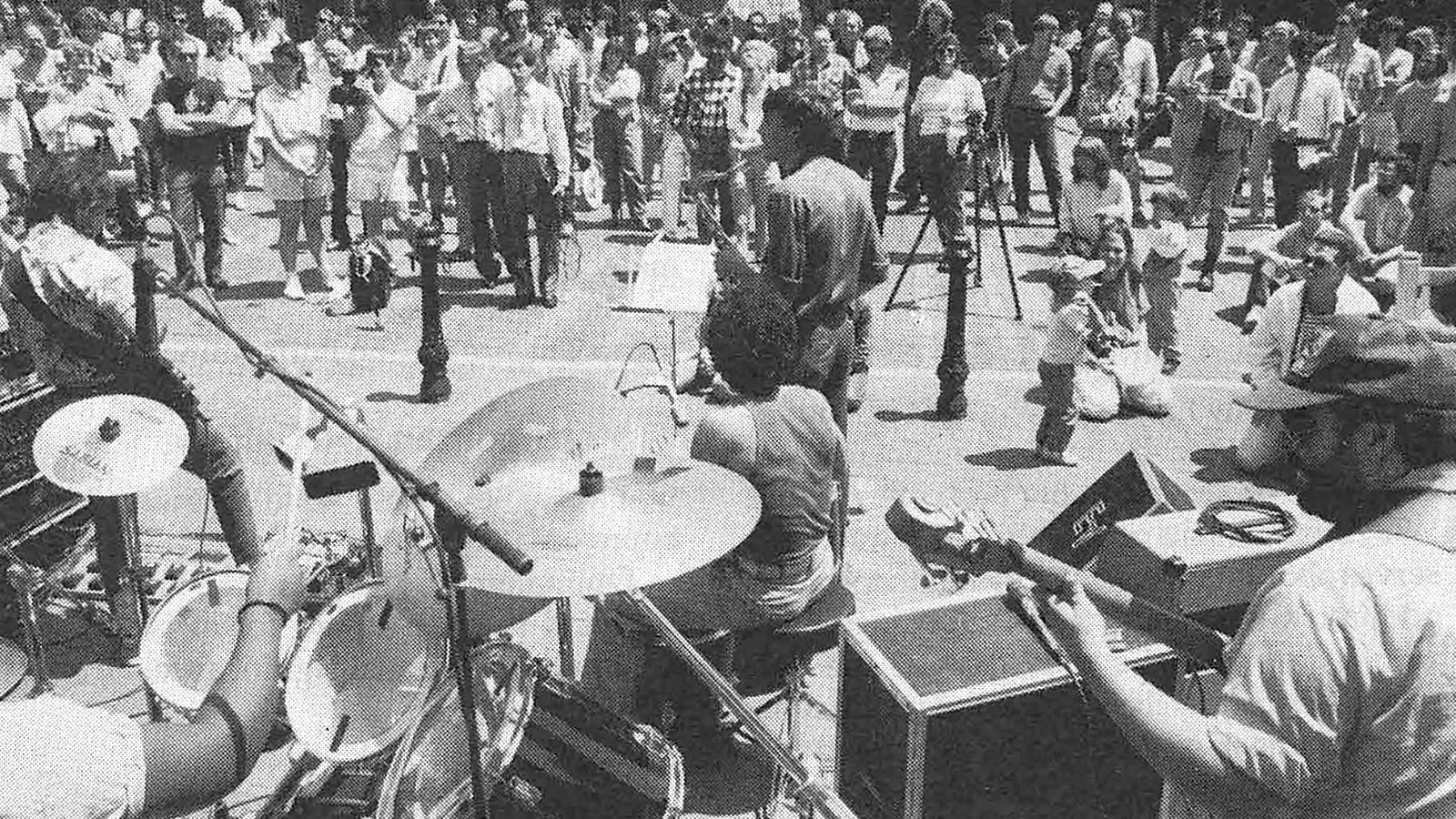

Music filled the streets of Burlington for the first time in years when Bernie was elected , enriching citizens’ lives and bolstering the music community, tourism, and hospitality.

“Pre-Bernie Burlington was home to antiquated, Footloose-style sound ordinances restricting the use of amplified music in city parks or public buildings, and in order to book a show at the city’s one auditorium, a promoter would have to appear before the city council to play a sample of the artists’ music and get approval.”[1]

“It was just mind-bogglingly stuck in the Fifties,” recalls Todd Lockwood, then owner of the local recording studio, White Crow Audio.”[1]

“But Mayor Sanders changed all that. “When he got into City Hall and cleaned house, suddenly we had music everywhere,” Lockwood says. Today, Burlington is home to one of the premier jazz festivals in North America and free concerts in the park every Thursday, and Lockwood credits Sanders for both.”[1]

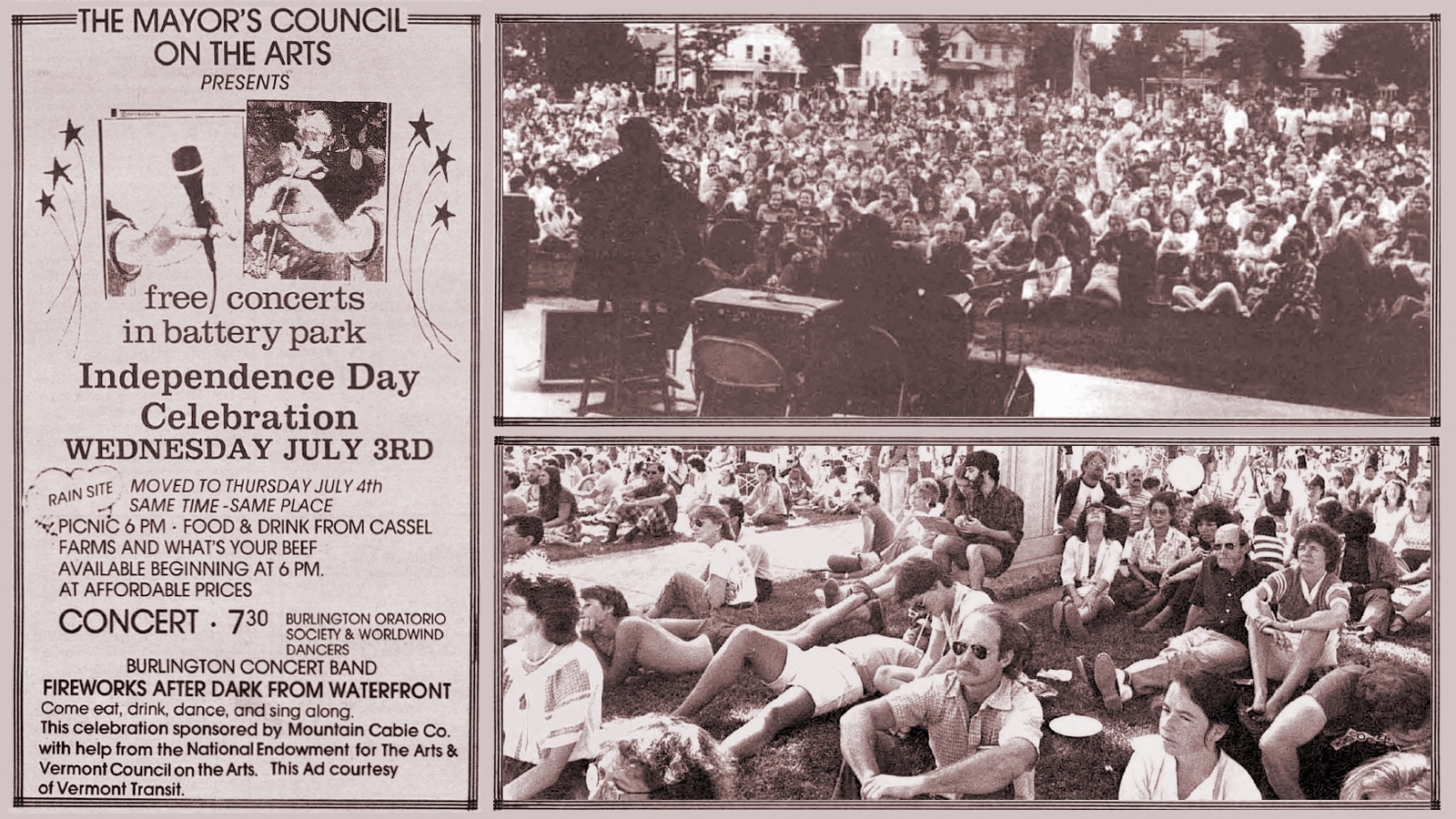

(Bernie) brought free outdoor concerts to Burlington’s Battery Park, and today, the Discover Jazz Festival continues to bring live music to Burlington each summer.[2] And in addition to outdoor festivals, the Mayor’s office also advocated for indoor venues to showcase local artists and touring acts year-round.

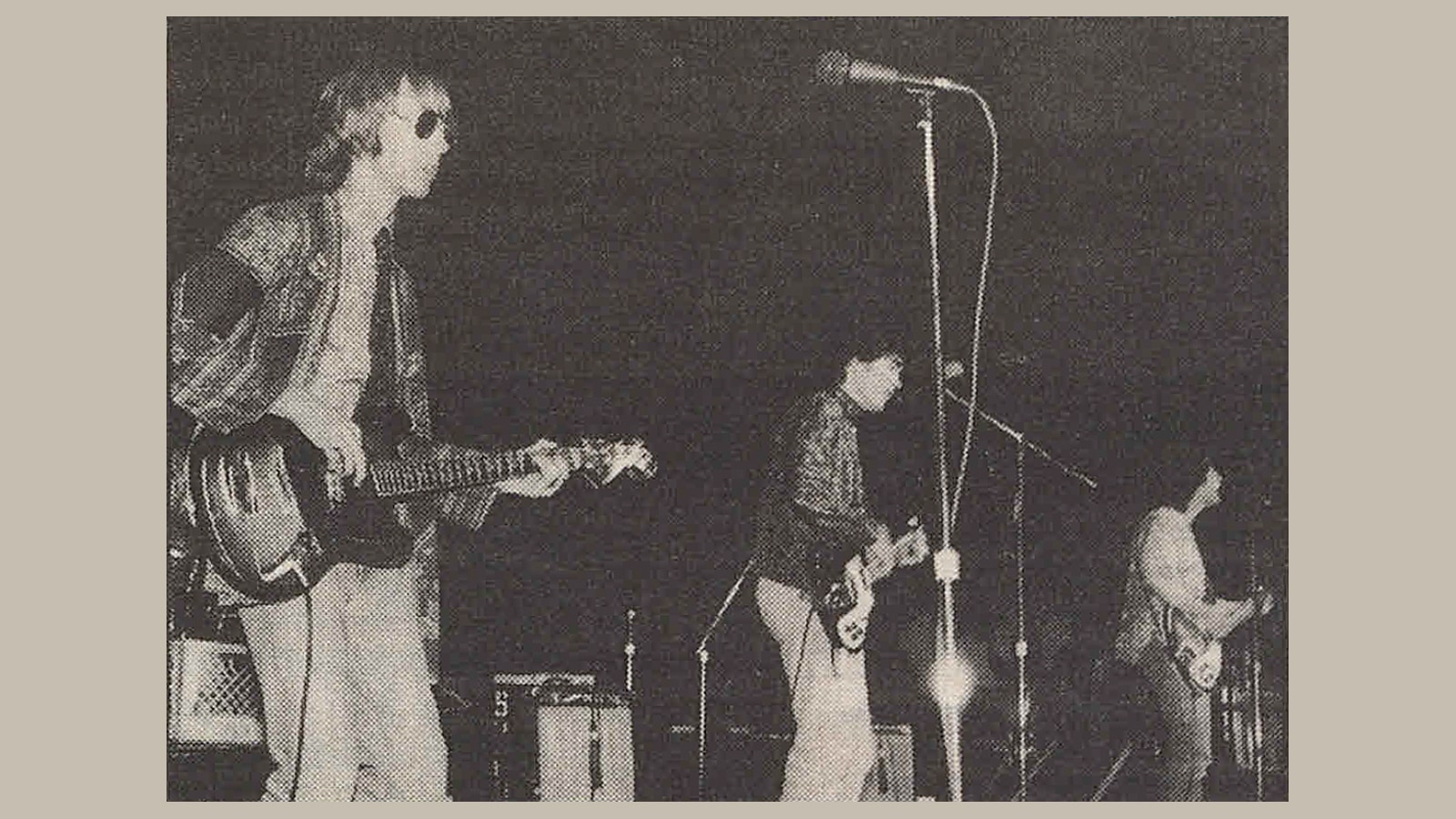

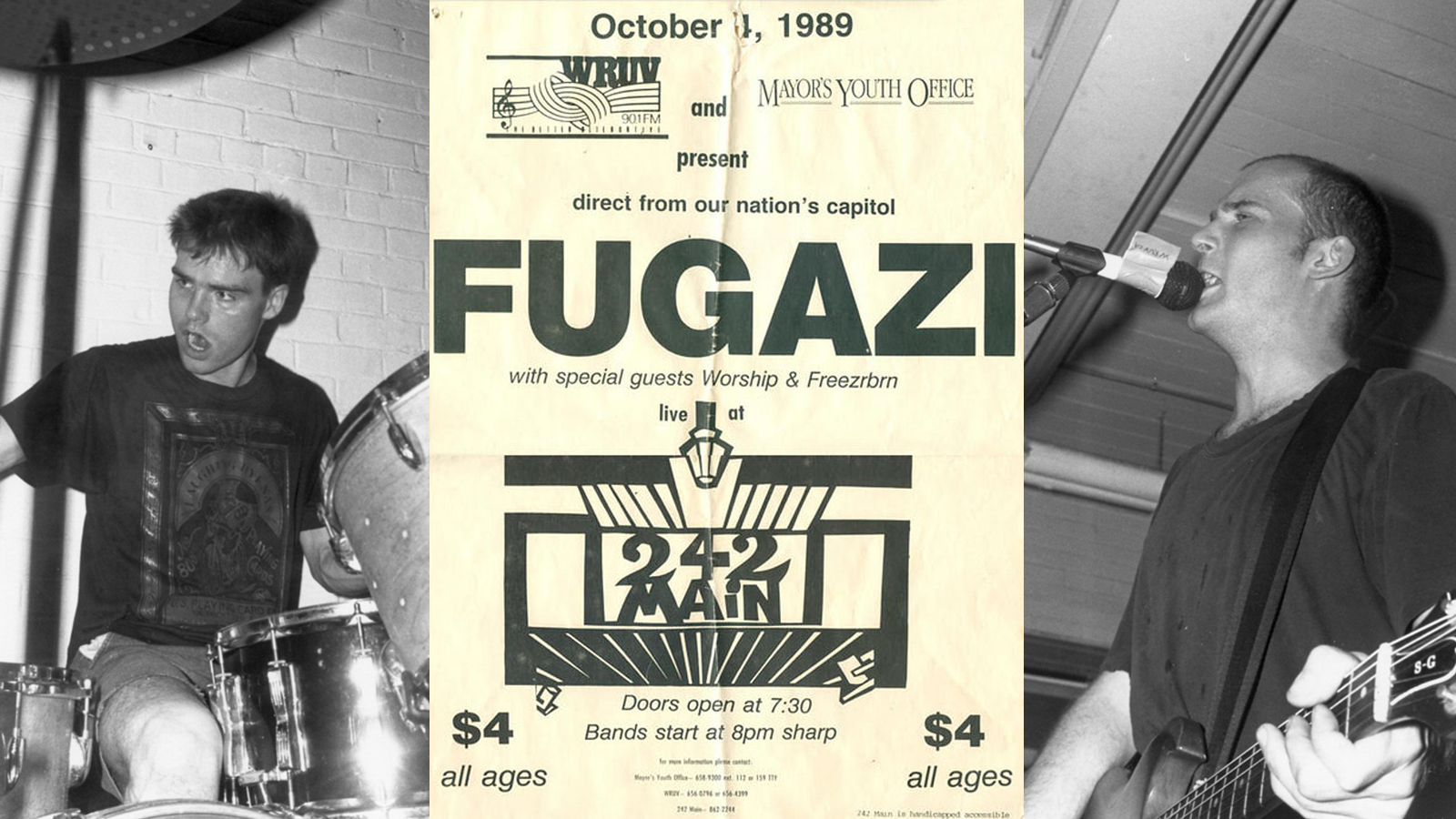

One of those venues, 242 Main Street, would go down in the annals of punk rock history as a legendary all-ages venue in the Northeastern U.S. punk scene.

“The impact 242 Main has had on Burlington music is incalculable,” said Dan Bolles, a music editor for Vermont alt-weekly Seven Days, who wrote a retrospective of the venue back in January. “You would be hard-pressed to find any rock musician who grew up in the area that hasn’t logged time on that stage at some point… It’s where most of us played our first shows and learned how to be in bands. Most of us eventually age out of 242 Main. But it’s a cornerstone in the musical upbringing of local youth to this day.”[3]

As Jane O’Meara Sanders tells it to VICE:

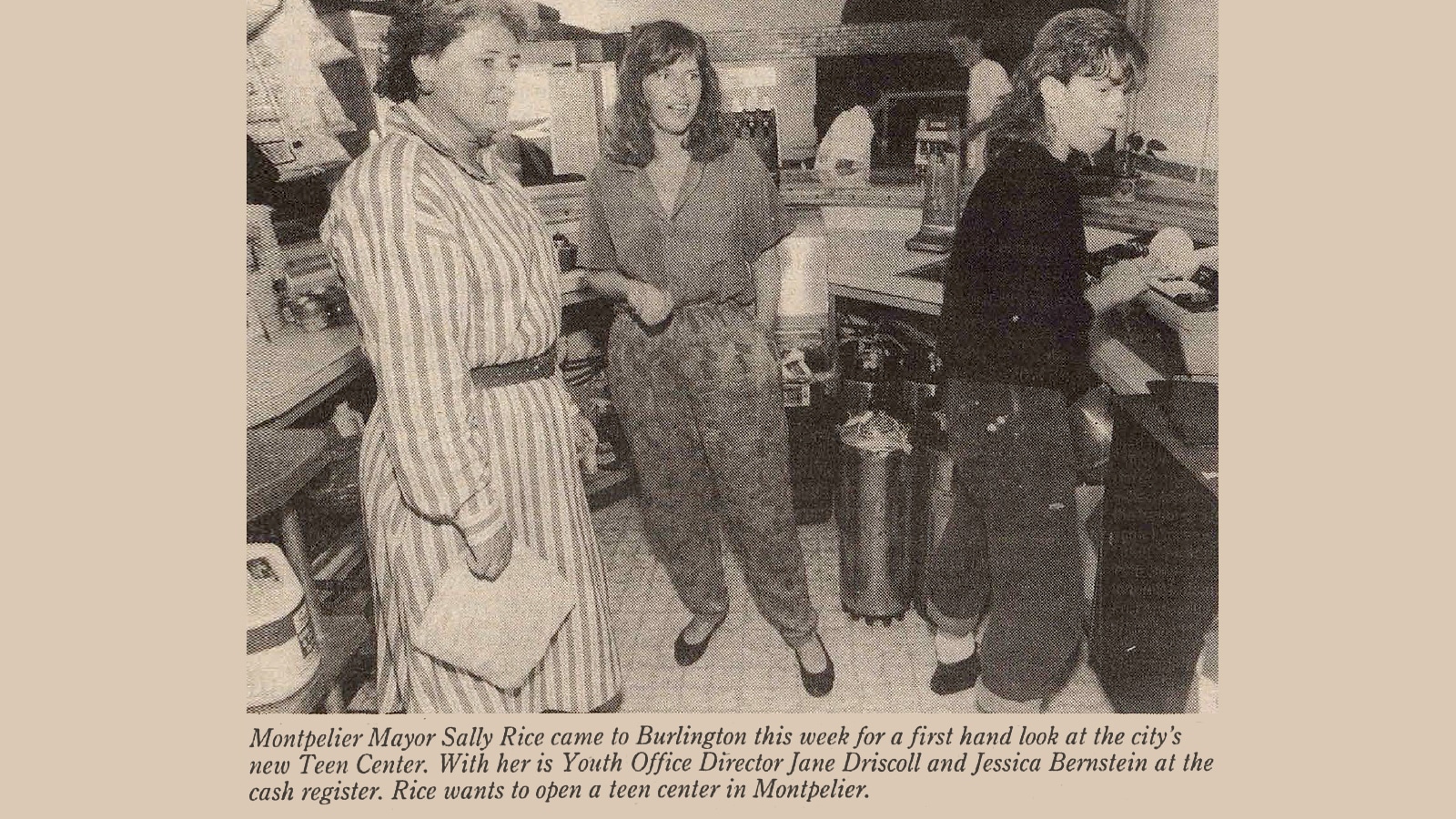

One of the main goals of the new youth office was to build a youth center in Burlington—and local teenagers made it clear that they wanted it to be an all-ages place where they could see and perform music. The problem was that a local ordinance passed during the previous administration prohibited live music performances on public property.

“We did a battle of the bands the first year – we got approval to do it that one time, and it was fantastic,” O’Meara Sanders said. “We had hundreds and hundreds of kids coming out for six bands, and it’s still going on to this day.”

After the first show’s success, the Mayor’s Youth Office started using a local auditorium for kids to play and watch music but found that it wasn’t an ideal spot. The solution was 242 Main, the vacated office of the Burlington Water Division.

During Bernie’s first presidential campaign, he made every effort to incorporate music and the arts into all aspects of his campaign, from videos by award-winning directors to rallies – dubbed political rock shows – with both national and local talent, and unprecedented campaign merchandise from noted visual artists. The result was an outpouring of originality that broke the mold in modern campaigning, which we will explore later in the timeline.

Bernie wanted America to have the same access to art that he fought for in Burlington. In 2016, Jacobin Magazine explained that vision:

“Now imagine if every county in the United States had an arts council as robust as Burlington’s: giving generous grants to individual artists and small arts companies; hosting free performances of music and theater; funding murals, sculptures, and more to exist in public spaces; providing free classes in art, theater, music, dance, and literature. Funds would be distributed locally to address the specific needs of each community. The result would be not only the enrichment of individuals but perhaps even a sea change in how the arts are perceived in the United States — not as remote and rarefied, inaccessible to all but the wealthiest and most educated, a “nice to have” rather than a “need to have,” but, as Bernie said, what life is about.”[2]

Back to Timeline

Back to Timeline