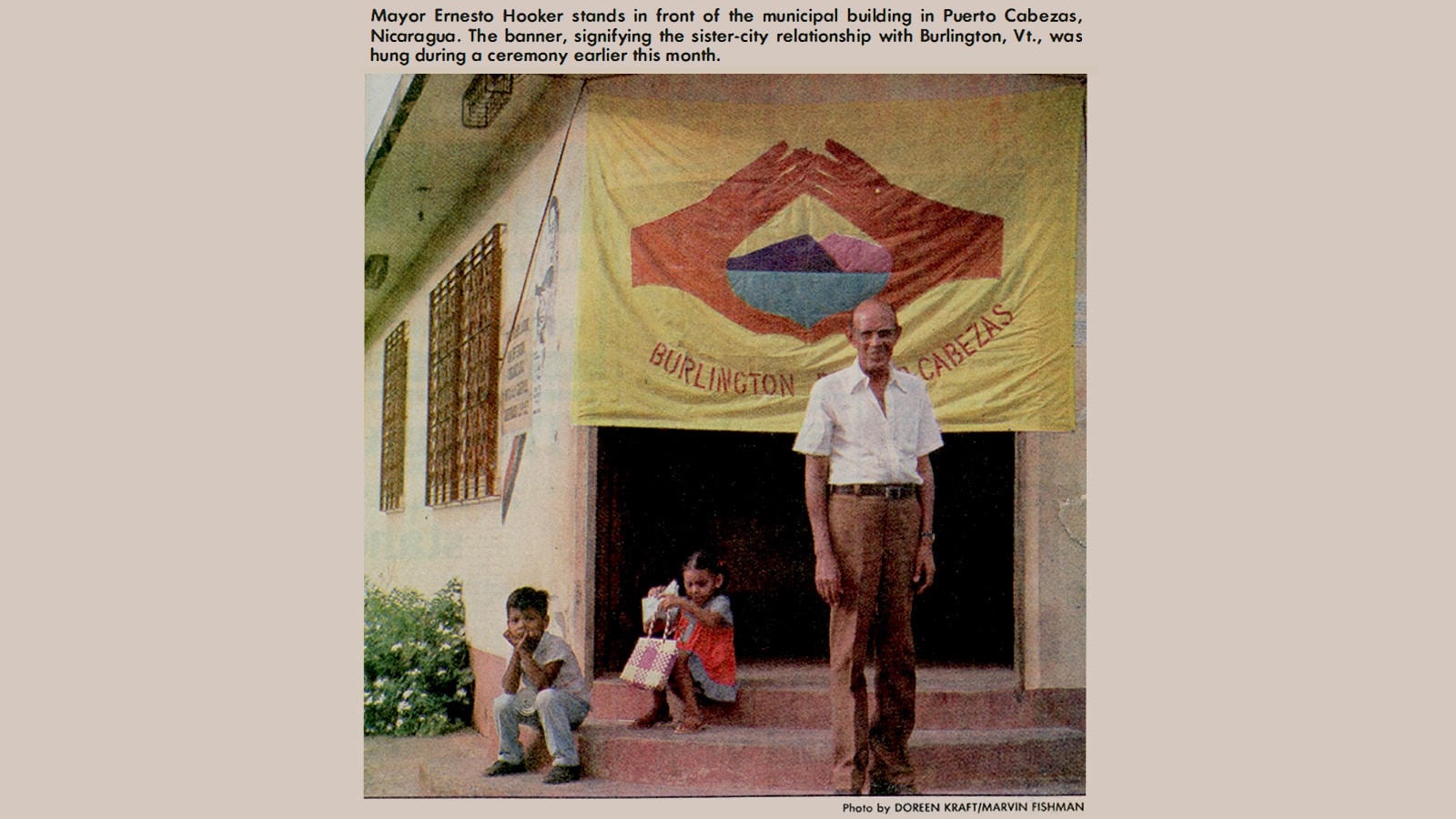

In 1984, Mayor Bernie Sanders established a sister city relationship between Burlington, Vermont, and Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, a city of 60,000 inhabitants on the North Atlantic coast. Bernie opposed the Reagan administration’s policies concerning Latin America and their support of the Contras and “considered it his small city’s responsibility to craft a foreign policy in opposition to the Reagan administration’s.”[1]

“People tried to portray (Bernie) as neglecting his mayoral responsibilities as he was doing these other international things,” acknowledged Terry Bouricius, a longtime Sanders confidante, and an alderman at the time, who dismissed the criticism. To the young socialist mayor, all politics was global.[1]

“[H]ow many cities of 40,000 have a foreign policy? Well we did,” he wrote in his memoir, “Outsider in the House.” “I saw no magic line separating local, state, national and international issues.”[2]

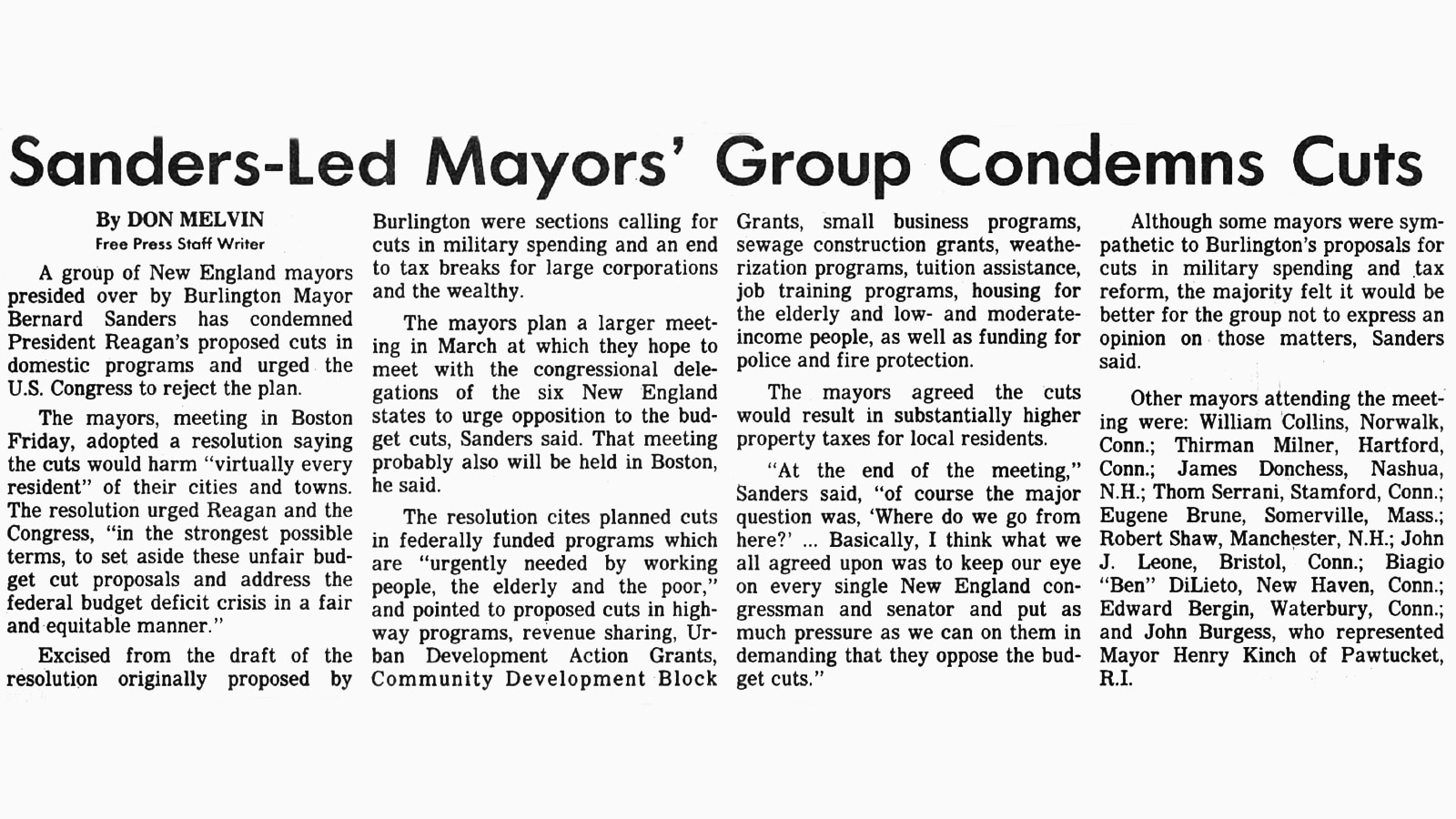

Bernie called an emergency meeting of the Burlington Aldermen after the House of Representatives voted to send $100 million in U.S. military aid to Nicaragua’s contra rebels. It was a major victory for Ronald Reagan’s hardline anti-communist foreign policy. The alderman’s meeting produced a vague plan for a donation to the Nicaraguan people, compensation for what Sanders called their suffering at the hands of the U.S.-backed contra rebels. (The tale is described in W.J. Conroy’s Challenging the Boundaries of Reform: Socialism in Burlington.) The result was, Sanders later conceded, “more symbolic than anything.”[1]

Bernie visited Nicaragua after establishing the sister city relationship.

In this CCTV town hall interview Bernie discussed his observations from the trip and longstanding thoughts on U.S. foreign policy in Central and Latin America. He also notes that he – a mayor in a town of 38,000 people – was the highest ranking American to visit Nicaragua during the celebration of their Revolution.

“Ever since I was a kid…I was always interested in the problems of Latin America and had done some reading about it as a young person and in college. One of the things that concerned me was the way that the United States government had always treated Latin America. And our history has always been that we have the right to unilaterally get involved and overthrow governments that we don’t like. I think at a certain point, one reaches the conclusion that if one believes in democracy – and that’s presumably what our nation is supposed to be about – how can you overthrow any government you don’t like? And if you study political science or economics, you understand that time and time again, these interventions have been to the benefit of large corporations. (So) should foreign policy be made for the benefit of large corporations that want to exploit the people of Latin and Central America?”[3]

He said of his seven-day visit to Nicaragua: “What I had the opportunity of doing down there is talking to real live people. I was very fortunate to talk to many of the government leaders – their President Ortega, (Father) Ernesto Cardinal (priest, poet, and revolutionary), and Thomas Jorge. But I also, quite intentionally, went out on the streets. We were going to the poorest neighborhoods of Managua and elsewhere…The response that I got among poor people and working people – and what one has to understand is that Nicaragua, while not the poorest country by any means in Central or Latin America, is a poor country. And you say, basically ‘how are things now, since the Revolution in 1979 as opposed to it before.’ And almost without exception – there were exceptions – no one should think that the Sandinista government has the support of 100% of the people. They most certainly do not. Among poor and working people, there was a very strong feeling that the Revolution that they had made was their Revolution. That they had fought against a very horrible Somoza dictatorship…most people felt that the situation was better now than it had been before. There were…serious concerns about the economic conditions in Nicaragua. And some of those people are blaming the government. But I think what should be understood is that problems exist all around Central and Latin America. I think many Americans are not aware of the horrendous conditions existing all around the third world.”[3]

He said of his seven-day visit to Nicaragua: “What I had the opportunity of doing down there is talking to real live people. I was very fortunate to talk to many of the government leaders – their President Ortega, (Father) Ernesto Cardinal (priest, poet, and revolutionary), and Thomas Jorge. But I also, quite intentionally, went out on the streets. We were going to the poorest neighborhoods of Managua and elsewhere…The response that I got among poor people and working people – and what one has to understand is that Nicaragua, while not the poorest country by any means in Central or Latin America, is a poor country. And you say, basically ‘how are things now, since the Revolution in 1979 as opposed to it before.’ And almost without exception – there were exceptions – no one should think that the Sandinista government has the support of 100% of the people. They most certainly do not. Among poor and working people, there was a very strong feeling that the Revolution that they had made was their Revolution. That they had fought against a very horrible Somoza dictatorship…most people felt that the situation was better now than it had been before. There were…serious concerns about the economic conditions in Nicaragua. And some of those people are blaming the government. But I think what should be understood is that problems exist all around Central and Latin America. I think many Americans are not aware of the horrendous conditions existing all around the third world.”[3]

When asked whether the Nicaraguan citizens were relatively sophisticated in their political views, he replied: “When you talk politics in Nicaragua, it is not like talking politics in the United States. In Nicaragua, what you’re talking about is life and death. It is a question about whether their children are going to have any kind of dignity or not.”

The successful sister city relationship has been an important part of Burlington’s modern history and was a great gift to the citizens of both cities, particularly the cultural exchanges.

“Over the years, Burlington has shipped to its sister city sizable quantities of material and humanitarian aid, including 500 tons of supplies on a “Peace Ship” in 1986, as well as agricultural supplies, educational materials, computers, video equipment, wheelchairs, and fire-fighting tools. Our first cultural exchange project was a book of photographs, Sister Cities: Side by Side, published in 1988. In 1990, Burlingtonians helped establish Puerto Cabezas’s Vivero Comunal, a community tree nursery. Official, educational, and cultural exchanges between the two cities have involved mayors, firefighters, drug-abuse counselors, photographers, visual artists, folk singers, college students, and entire Little League baseball teams. We are currently working to support Puerto Cabezas in developing a community action plan for sustainable development.”[4]

Back to Timeline

Back to Timeline