In 1997, Rep. Bernie Sanders introduced “Child Labor Deterrence Act” and “The Bonded Child Labor Elimination Act,” two measures to combat child labor laws, including an amendment to combat the exploitation of child labor while promoting better economic policy; and a ban on the importation of any product made using child or indentured labor.

“Exploited children toil in factories, mines, fields, at looms, and even in brothels, sacrificing their youth, health, and innocence for little or no wages. They are hand stitching the Nike and Adidas soccer balls our kids practice with daily. The same soccer balls used at the Atlanta Olympics last year. They sew the blouses, slacks, and shirts millions of us have purchased and worn. They are making Mattel Barbie dolls that little girls all across America play with,” said Sanders.[1]

He continued, “The irony here is that many of these same products that are now being produced by exploited children in Latin America, China, India, Pakistan, and other countries, used to be manufactured by American workers here in the United States, who earned a living wage. However, Corporate America found that their profits could soar by running to desperate third-world countries and exploiting children. So, American workers lose their jobs, and kids around the world are paid 20 or 50 cents an hour to produce products for American multinational corporations.”[1]

“These measures will prohibit importing products into the American marketplace made by children under 14 who are employed in manufacturing or mining and prohibit importing any products made by children in bondage. We think this is the right thing to do, and it’s a good economic policy. This is a moral issue about whether or not we as a nation should be allowing the importation of products made by children — some living in virtual slavery. It’s also an economic issue. What type of trade policy lets American workers be thrown out on the street and allows companies to go abroad and manufacture products made by children making 20 or 30 cents an hour? It doesn’t make any sense to me,” Sanders concluded.[1]

A week after introducing the measures, Sanders was invited to the White House for the announcement of the anti-sweatshop initiative. The anti-sweatshop agreement, “The Apparel Industry Partnership,” was reached by a presidential task force created in August 1996 by former Labor Secretary Robert Reich. The task force was a coalition of major apparel manufacturers, labor, and human rights groups.[2]

Under the agreement, a code of conduct on wages and working conditions would be negotiated for American companies’ apparel factories worldwide. A newly created industry association would oversee monitors who inspect garment factories and give a seal of approval to companies that comply with the code of conduct. Companies that comply with the code would then be able to put a label on their clothing informing customers that it was not made in a sweatshop.[2]

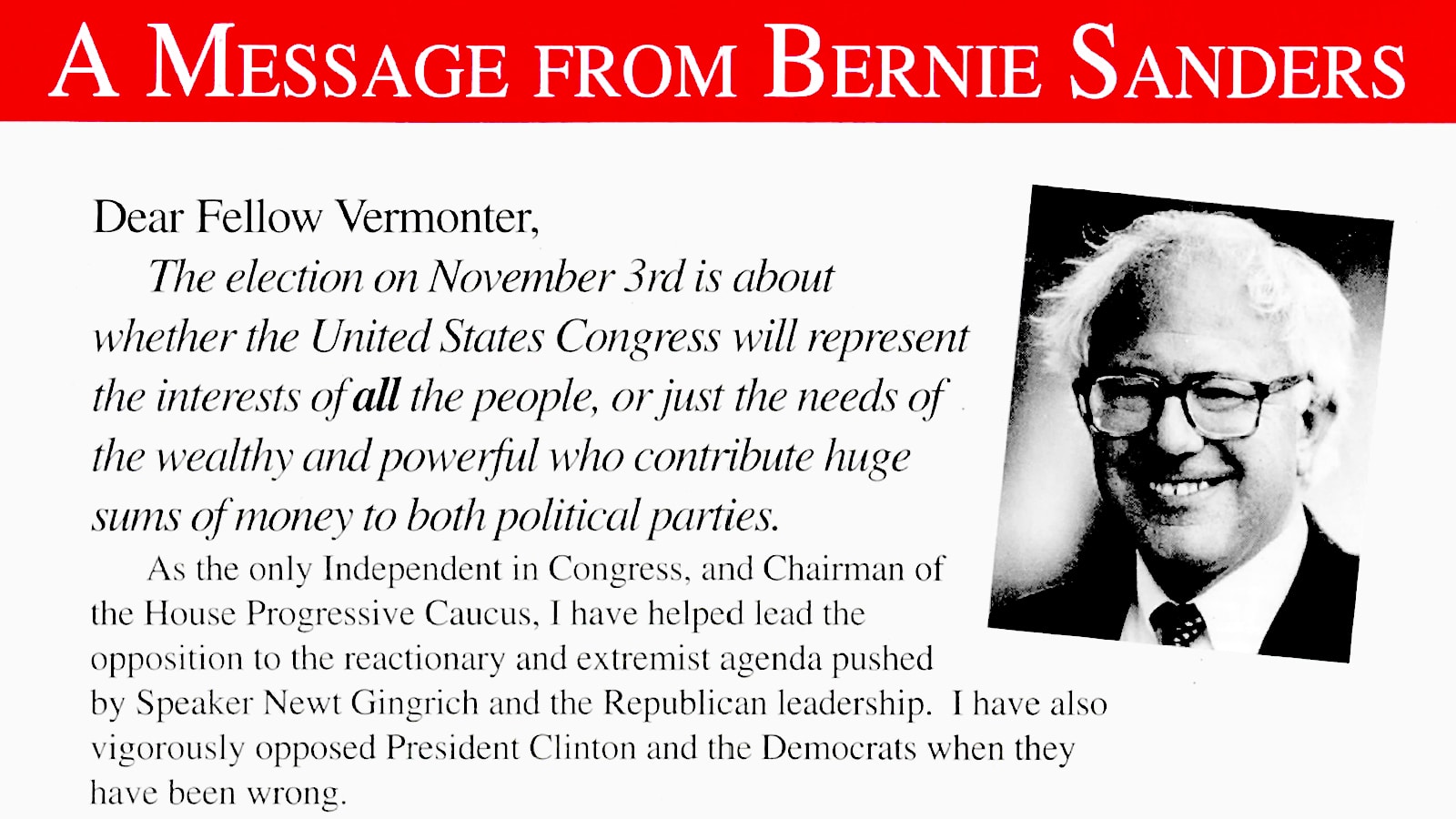

However, Sanders said he was disturbed by the task force’s position in the wage agreement. The group had only recommended that factories pay the legal minimum wage in the country where they are located.[2]

Sanders said, “This is an issue that I have been working on for a number of years, and I am delighted that it is now getting attention from the White House. This agreement is a good first step, but we have a long way to go. Congress should pass legislation banning the import of any products made by child labor. It is unacceptable that Third World children are now doing work at 20 cents an hour that American workers used to perform at a living wage. We must continue to demand that corporate America reinvest in this country and not hire desperate Third World children at starvation wages. We need to make fundamental changes in our trade policy.”[2]

In September 1997, Sanders’ amendment passed the House, effectively prohibiting the importation of any product made by forced or indentured child labor. The amendment, part of the Treasury and Postal Services Appropriations bill, was signed by President Bill Clinton in October 1997 as part of the $24.7 billion U.S. Treasury spending bill.[3]

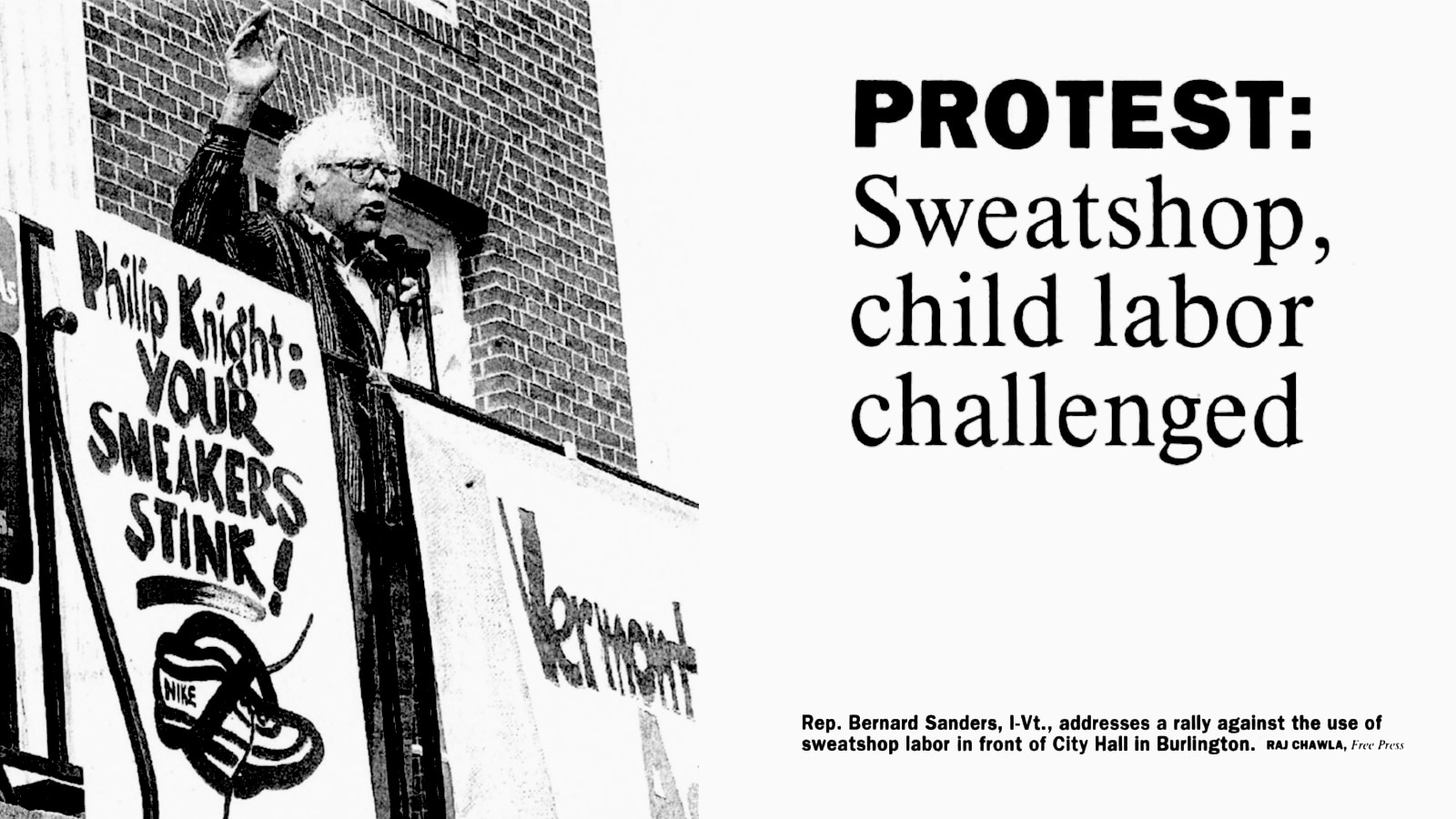

The bill coincided with a series of Vermont rallies led by The Vermont Coalition Against Sweatshop Labor – a new statewide organization of political, religious, labor, and student activists. The group urged Vermonters to boycott products made by grossly underpaid workers and children.[3]

“We’re dealing with a moral issue,” said Sanders. “We in the United States of America, should not be aiding and abetting in the virtual slavery of Third World women and children.”[3]

Back to Timeline

Back to Timeline