How Oligarchs Shrank America’s Middle Class

Despite an economy that’s far larger and more productive than it was 40 or 50 years ago, the typical American worker has gone nowhere.

When I was a boy, my father sold dresses and blouses to the wives of factory workers. As the wages of those workers rose through the 1950s, my father earned enough to expand his business to a second shop in another factory town not far away. We were by no means rich, but he earned enough to put us in the middle class.

For three decades after World War II, the average hourly compensation of American workers rose in lockstep with the nation’s productivity gains. In other words, as workers produced more value, they got more pay.

It was a virtuous cycle, from which our family and tens of millions of others benefited: The economy grew, and the middle class expanded. Its purchasing power rose, causing the economy to grow faster. This fueled new investments and innovations that further enriched and enlarged the middle class.

But then, beginning in the late 1970s, the virtuous cycle came to a halt.

While productivity gains continued much as before and the economy continued to grow, wages began to flatten. Starting in the early 1980s, the median household’s income stopped growing altogether, when adjusted for inflation.

Today, the median household is earning just a bit more than it did in 1979, 45 years ago (adjusted for inflation).

If you’re a non-supervisory worker who relies on an hourly wage — still the vast majority of workers — you’re earning no more than you earned in 1969. Job security also declined.

So, despite an economy that’s far larger and more productive than it was 40 or 50 years ago, the typical American worker has gone nowhere.

The standard explanation attributes this to neutral “market forces,” especially globalization and technological innovations that have made many working Americans less competitive.

While surely important, the standard explanation can’t account for much of what’s happened. It doesn’t explain why the transformation occurred so suddenly, over a relatively small number of years. Nor why other advanced economies facing similar forces didn’t succumb to them. Nor why so much of the nation’s income and wealth have gone to the top.

America’s middle class has shrunk because of its declining bargaining power — orchestrated and directed by America’s oligarchy. The economic gains that would otherwise have gone to the middle class went instead to the moneyed interests at the top. Let me explain.

1. The financialization of the economy

Before the 1980s (as I noted in our discussion about the decline of the common good), large corporations were in effect owned by all their stakeholders, who were assumed to have legitimate claims on them.

As early as 1914, the popular columnist and public philosopher Walter Lippmann called on America’s corporate executives to be stewards of America. “The men connected with [the large corporation] cannot escape the fact that they are expected to act increasingly like public officials …. Big businessmen who are at all intelligent recognize this. They are talking more and more about their ‘responsibilities,’ and their ‘stewardship.’”

This vision of corporate governance came to be widely accepted by the end of World War II. Frank Abrams, chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey, declared in a 1951 address that typified what other chief executives were saying at the time:

“The job of management is to maintain an equitable and working balance among the claims of the various directly affected interest groups … stockholders, employees, customers, and the public at large. Business managers are gaining professional status partly because they see in their work the basic responsibilities [to the public] that other professional men have long recognized as theirs.”

Pulp and paper executive J.D. Zellerbach told Time magazine that “[t]he majority of Americans support private enterprise, not as a God-given right but as the best practical means of conducting business in a free society … . They regard business management as a stewardship, and they expect it to operate the economy as a public trust for the benefit of all the people.”

But a radically different vision of corporate ownership emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It came from corporate “raiders” who mounted hostile takeovers with high-yield junk bonds.

The raiders used leveraged buyouts and undertook proxy fights against the “industrial statesmen” who, in their view, were depriving shareholders of the wealth that properly belonged to them.

The raiders assumed shareholders were the only legitimate owners of the corporation and that the only valid purpose of the corporation was to maximize shareholder returns.

This transformation did not happen by accident. It was a product of changes in laws governing corporations and of financial markets — changes that were promoted by the monied interests, America’s oligarchs.

In 1974, at the urging of pension funds, insurance companies, and Wall Street, Congress enacted the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. Before then, the giant portfolios of pension funds and insurance companies could be invested in only high-grade corporate and government bonds. Legally, it was their fiduciary obligation.

The 1974 Act changed that, allowing pension funds and insurance companies to invest in the stock market — thereby making a huge pool of capital available to Wall Street.

In 1982, another large pool of capital became available when Congress allowed savings and loan banks — the bedrocks of local home mortgage markets — to invest their deposits in a wide range of financial products, including junk bonds and other risky ventures promising high returns.

The convenient fact that the government insured savings and loan deposits against losses made these investments all the more tempting (and ultimately cost taxpayers some $124 billion when many of the banks went bust).

Meanwhile, the Reagan administration loosened other banking and financial regulations and simultaneously cut the enforcement staff at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

All this made it possible for corporate raiders to get the capital and the regulatory approvals they needed to mount unfriendly takeovers.

During the whole of the 1970s, there had been only 13 hostile takeovers of companies valued at $1 billion or more. During the 1980s, there were 150.

Even where raids did not occur, CEOs felt pressured to maximize shareholder returns for fear their firms might otherwise be targeted. Hence, they began to see their primary role as driving up share prices.

The easiest and most direct way for CEOs to accomplish this feat was to cut costs — especially payrolls, which constitute most firms’ largest single expense.

Accordingly, the corporate statesmen of the 1950s and 1960s were replaced by the corporate butchers of the 1980s and 1990s, whose nearly exclusive focus was to “cut out the fat” and “cut to the bone.”

When Jack Welch took the helm of GE in 1981, the company was valued by the stock market at less than $14 billion. When he retired in 2001, it was worth about $400 billion. Welch accomplished this largely by cutting payrolls.

Before his tenure, most GE employees had spent their entire careers with the company. But between 1981 and 1985, a quarter of them — 100,000 in all — lost their jobs, earning Welsh the moniker “neutron Jack.” Even when times were good, Welch encouraged his senior managers to replace 10 percent of their subordinates every year in order to keep GE competitive.

Other CEOs tried to outdo even Welch. As CEO of Scott Paper, “Chainsaw” Al Dunlap laid off 11,000 workers, including 71 percent of headquarters staff. Wall Street was impressed, and the company’s stock soared.

When Dunlap moved to Sunbeam in 1997, he promptly laid off half of Sunbeam’s 12,000 employees. (Unfortunately for Chainsaw Al, he was caught cooking Sunbeam’s books; the SEC sued him for fraud, and he settled for $500,000, agreeing never again to serve as an officer or director of any publicly held company.)

In consequence of this change in the purpose of the American corporation, share prices soared, as did the compensation packages of CEOs. The results have been touted as “efficient” because resources theoretically have been shifted to “higher and better uses.”

But the human costs of this transformation have been huge. Millions of workers have lost jobs and wages. Many communities have been abandoned.

Nor have the efficiency benefits been widely shared.

As corporations have steadily weakened their workers’ bargaining power, the link between productivity and workers’ income has been severed.

Almost all the gains from growth have gone to the top. As noted, the average worker today is no better off than his or her equivalent 40 years ago, adjusted for inflation. Most are less economically secure.

Not incidentally, few own any shares of stock.

The richest 1 percent of Americans now own 52 percent of all the shares of stock owned by Americans. The richest 10 percent, 93 percent. The nation’s economic gains, once distributed broadly to the working and middle class — have been siphoned to the top.

2. Globaloney

Wages have also been suppressed because workers who are worried about keeping their jobs have accepted lower pay, relative to the economy’s productivity gains, than they did 40 years ago.

Here again, political decisions steered by the nation’s oligarchy have played a significant role. Some of the prevailing job insecurity is the result of trade agreements that invited American companies to outsource jobs abroad.

The conventional view equating “free trade” with the “free market” — in contrast to government “protectionism” — is wrong.

Just as all nations’ markets reflect political decisions about how they should be organized, so-called “free trade” agreements entail complex negotiations about how different market systems are integrated.

Within these negotiations, the interests of large corporations and Wall Street, to fully protect the value of their intellectual property and financial assets, have repeatedly trumped the interests of average working Americans to protect the value of their labor.

When the Federal Reserve raises interest rates and Congress opts for austerity to reduce federal budget deficits — two policies favored by the oligarchy — the resulting unemployment also undermines the bargaining power of average workers.

3. The Fed and inflation

When the Federal Reserve raises interest rates and Congress opts for austerity to reduce federal budget deficits — two policies favored by the oligarchy — the resulting unemployment also undermines the bargaining power of average workers.

Higher unemployment keeps wages low. This means higher corporate profits, leading to higher returns for shareholders.

The high inflation after the pandemic was driven in part by supply shortages and a major government stimulus. But it was also driven by monopolistic corporations using the excuse of inflation to raise their prices.

The Fed, however, believed that a root cause of inflation was wage growth, and it set out to slow the economy and loosen the labor market by raising interest rates. Here, too, the strategy was consistent with the views of the moneyed interests and was pushed by them.

4. The risk-shift to workers

Public policies that emerged during the New Deal and World War II placed most of the risks of economic change on large corporations rather than workers — through Social Security, worker’s compensation, 40-hour workweeks with time-and-a-half for overtime, and employer-provided health benefits (wartime price controls encouraged such tax-free benefits as substitutes for wage increases).

By the 1950s and 1960s, a majority of the employees of large companies remained with the companies for life. Their paychecks rose steadily with seniority, productivity, the cost of living, and corporate profits. When they retired, they received generous corporate pensions.

But after the junk-bond and takeover mania of the 1980s, that relationship broke down.

Even full-time workers who have put in decades with a company can now find themselves without a job overnight — with no severance pay, no help finding another job, no health insurance, and little or no pension.

Nearly one out of every five working Americans is now in a part-time job. Many are temporary workers, freelancers, independent contractors, or consultants, whose incomes and work schedules vary from week to week or even day to day. Two-thirds of American workers are living paycheck to paycheck.

The risk of getting old without a pension is rising.

In 1980, more than 80 percent of large and medium-sized firms gave their workers “defined-benefit” pensions that guaranteed them a fixed amount of money every month after they retired.

Now, fewer than 10 percent of companies provide their workers defined-benefit pensions. Instead, they offer “defined contribution” plans whose risks have been shifted to the workers. When the stock market tanks, as it did in 2008 and then again in 2020, their 401(k) plans tank along with it.

A quarter of all workers with so-called “matching” defined-benefit plans get no match because they don’t earn enough to contribute to them.

Meanwhile, the risk of a sudden loss of income continues to rise. Even before the crash of 2008, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics at the University of Michigan found that over any given two-year stretch, about half of all families experienced some decline in income.

Those downturns have become progressively larger. In the 1970s, the typical drop was about 25 percent. By late 1990s, it was 40 percent. By the mid-2000s, family incomes rose and fell twice as much as they did in the mid-1970s, on average.

Workers who are economically insecure are not in a position to demand higher wages. They are driven more by fear than by opportunity.

This is another central reality of American capitalism as organized by those with the political power to make it so.

5. The demise of labor unions

Fifty years ago, when General Motors was the largest employer in America, the typical GM worker earned $35 an hour in today’s dollars.

Today, America’s largest employer is Walmart, and the typical entry-level Walmart worker earns about $11 an hour.

This doesn’t mean the typical GM employee a half-century ago was “worth” four times what the typical Walmart employee today is worth. The GM worker was not better educated or motivated than today’s Walmart worker.

The real difference is that GM workers a half-century ago had a strong union behind them that summoned the collective bargaining power of all autoworkers to get a substantial share of company revenues for its members.

Because more than a third of workers across America then belonged to a labor union, the bargains those unions struck with employers raised the wages and benefits of non-unionized workers as well. Non-union firms knew they would be unionized if they did not come close to matching the union contracts.

Today’s Walmart workers do not have a union to negotiate a better deal. They are on their own. Because only 6 percent of today’s private-sector workers are unionized, most employers across America have no incentive to match union contracts. This puts unionized firms at a competitive disadvantage.

The result has been a race to the bottom.

Some argue that the decline of American unions is simply the result of “market forces.” But other nations have been subject to many of the same “market forces” and continue to have strong unions. In Sweden, 90 percent of workers in the private sector are unionized. These unions continue to provide their middle classes sufficient bargaining power to command a significant share of economic growth — a much larger share than that received by the middle class in the United States.

Why the difference? Look to politics and the allocation of power.

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 guaranteed American workers the right to organize into unions and imposed on employers the legal responsibility to bargain with them.

As unions gained economic power in the late 1930s and 1940s, they gained greater. political power and wielded it to further enlarge the bargaining clout of American workers. After the legendary Treaty of Detroit in 1950, when Big Business and Big Labor agreed to share productivity gains in exchange for labor peace, the rate of unionization increased dramatically, as did wages and benefits.

Which is why, by the mid-1950s, almost a third of all American employees in the private sector of the economy belonged to a union, and why the median wage increased in tandem with productivity growth.

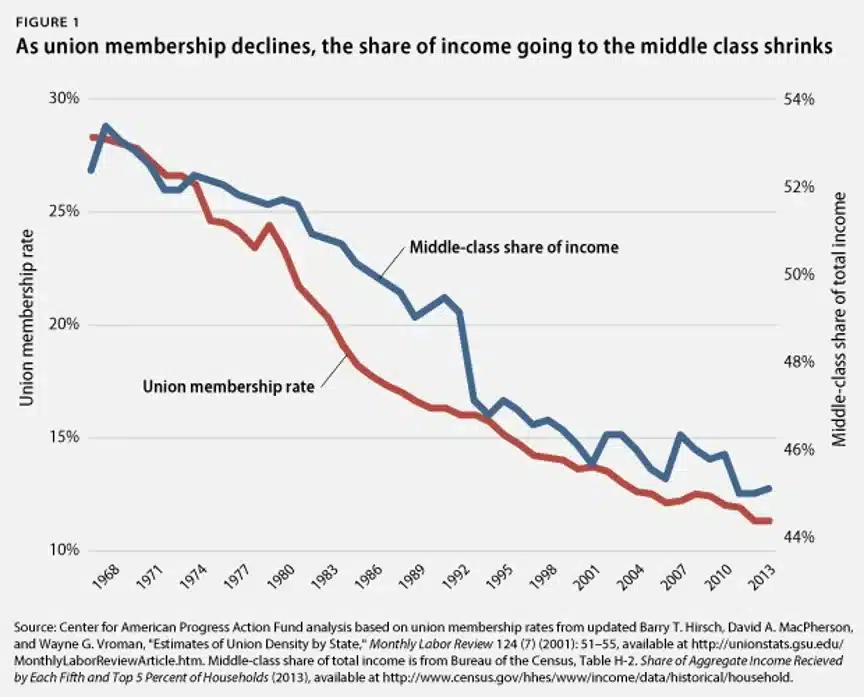

But starting in the late 1970s, the process went into reverse. Union membership began to decline, as did the economic and political power of unions, along with the bargaining clout of most workers.

The reasons for the decline involved the changes I’ve already noted — globalization, labor-replacing technologies, and a shift in the purpose of the corporation to maximizing shareholder returns.

But the decline of labor unions was also the consequence of political and legal decisions demanded by the monied interests.

When the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 allowed states to enact “right-to-work” laws, workers who did not pay dues got a free ride off of those who did, thereby undermining the incentive for anyone to join a union in the first place.

Until the 1980s, such laws had minimal effect because they were enacted in southern and western states. Most industries remained in the north.

But as corporations came under increasing pressure to show high returns and cut labor costs, many CEOs found “right-to-work” states more alluring. Even the old heartland industrial states of Indiana and Michigan have enacted “right-to-work” laws.

CEOs whose corporations had high percentages of unionized workers moved, or threatened to move, to “right-to-work” states.

Additionally, Reagan’s notorious firing of the nation’s air traffic controllers for going on strike (which he had a right to do because they had no right to strike) signaled to the nation’s large employers that America had embarked on a different era of labor relations.

Workers who inhabited the local service economy — retail, restaurants, custodial, hotels, elder and child care, hospitals, transportation — faced a different challenge. Their jobs were in less danger of disappearing, because they couldn’t be outsourced abroad and most would not be automated. In fact, the number of local service jobs in America has continued to grow.

But because so many workers expelled from the older industrialized economy had no choice but to seek local service jobs, service-sector employers easily found people willing to work for low wages, few benefits, and little chance of advancement.

Walmart and major fast-food chains, such as Starbucks, have been aggressively anti-union. They’ve blocked union votes, fired workers who tried to organize, refused to enter into contract negotiations, and intimidated others into rejecting the union — all in violation of the National Labor Relations Act.

A succession of Democratic presidents have promised legislation streamlining the process for forming unions and increasing penalties on employers who violate the law, but nothing has come of these promises. (President Biden has been the first to strengthen the National Labor Relations Board and encourage it to enforce the law.)

The result of all this has been a steady decline in the percentage of private-sector workers who are unionized. Despite the jolt of labor activism in 2023, that percentage continues to drop.

The decline parallels the declining share of total income going to the middle class.

Take a look:

6. Summary

The underlying problem is that average working Americans have steadily lost the bargaining power to receive as large a portion of the economy’s gains as they received in the first three decades after World War II. As a result, instead of the middle class growing, it has shrunk.

To attribute this to the impersonal workings of the “free market” is to ignore how the market has been reorganized since the 1980s. America’s oligarchs — the moneyed interests — have spearheaded this reorganization in order to receive a steadily larger share of the nation’s economic gains. As those gains have risen, so has the oligarchy’s power to accumulate even more.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Next week we’ll look at whether — and how — countervailing power can be restored so that more of America’s poor and working class can ascend into the middle class once again.