The “National Debt” Is No One’s Fault

On March 27, 2018, a group of economists from the conservative Hoover Institution published an op-ed declaring that A Debt Crisis is on the Horizon. They wrote:

For years, economists have warned of major increases in future public debt burdens. That future is on our doorstep…Unless Congress acts to reduce federal budget deficits, the outstanding public debt will reach $20 trillion a scant five years from now, up from its current level of $15 trillion…When treasury debt holders start to doubt our government’s ability to repay, or to attract future lenders, they will demand higher interest rates to compensate for the risk…Such high interest payments would crowd out financing of needed expenditures to restore our depleted national defense budget, our domestic infrastructure and other critical government activities…

About a week later, five former chairs of the White House Council of Economic Advisors—including Janet Yellen and Jason Furman—countered with an op-ed of their own. They titled it A Debt Crisis is Coming. But Don’t Blame Entitlements. Here’s their opening paragraph. Notice how it affirms rather than counters the core of the conservative argument.

A group of distinguished economists from the Hoover Institution, a public-policy think tank at Stanford University, identifies a serious problem. The federal budget deficit is on track to exceed $1 trillion next year and get worse over time. Eventually, ever-rising debt and deficits will cause interest rates to rise, and the portion of tax revenue needed to service the growing debt will take an increasing toll on the ability of government to provide for its citizens and to respond to recessions and emergencies. None of that is in dispute.

As a reader of The Lens, you know that when the debate is broadened to include voices like mine, all of that is in dispute. But among establishment figures on both sides of the political aisle, there is shared agreement that something must be done to address America’s looming debt problem.

Thus, the debate—such as it is—revolves around who’s policies got us into this (supposed) mess, what we should do about it, and how much time we have to address the so-called problem.

That debate will intensify tomorrow, when President Biden meets with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) to discuss raising the debt limit. McCarthy has made it clear that republicans are seeking (unspecified) spending cuts in exchange for their help in lifting the debt ceiling. Meanwhile, the White House says it’s in no mood to negotiate. The president wants a clean vote to raise the debt limit, and he has threatened to “veto everything” if Congress sends him a deal that includes spending cuts that would jeopardize the economic recovery.

It’s anyone’s guess as to how this ends. But one thing is clear: no one in either party seems to want to have an honest conversation with the American people. Already, lawmakers from both sides of the political aisle are talking and tweeting about how our (supposed) debt dilemma is mostly the fault of the other party.

You could argue that it’s endemic to our politics. I know from my time working for the democrats on the US Senate Budget Committee that messaging is everything and that politicians rarely stray from their talking points. There is also comfort in the familiar.

Pointless Finger-Pointing

It’s not that there isn’t a cohort of lawmakers who have been exposed to alternative ways of thinking about these issues. It’s that most of them haven’t figured out how to talk to the American people without starting from the shared premise that our nation is facing a serious debt problem. And once you concede that there’s a debt crisis, you have little choice but to identify the culprit.

Unfortunately, you find the same finger-pointing among economists.

For example, the conservative economists at the Hoover Institution pointed the finger at programs like Social Security and Medicare, singling them out as the main drivers of our (supposed) debt crisis:

As is well-known, our deficit and debt problems stem from sharply rising entitlement spending…To address the debt problem, Congress must reform and restrain the growth of entitlement programs and adopt further pro-growth tax and regulatory policies…If Congress acts now, it can avoid a fiscal collapse…It is time for action.

Not so fast, said the former CEA chairs who served under democratic administrations:

It is dishonest to single out entitlements for blame…[They] are not the primary cause of the recent jump in the deficit…The federal budget was in surplus from 1998 through 2001, but large tax cuts and unfunded wars have been huge contributors to our current deficit problem. The primary reason the deficit in coming years will now be higher than had been expected is the reduction in tax revenue from last year’s tax cuts, not an increase in spending.

In other words, our guy (President Clinton) presided over a balanced budget, and then your guy (President G.W. Bush) came in and piled on a bunch of debt with his tax cuts and “unfunded” wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Yes, we’re in trouble, but it’s your fault, not ours.

It’s so counterproductive.

The pandemic gave us a brief reprieve from this pointless finger pointing, as democrats and republicans—working together—used fiscal deficits to shore up the balance sheets of families, businesses, and state & local governments. When reporters raised concerns about how much money the government was preparing to spend, President Trump dismissed any cause for alarm, explaining, “It’s $6.2 trillion and we can handle that easily because…it’s our money. It’s our currency.”

I hate to tell you, but he was right.

Well, there’s that. “It’s our money. It’s our currency.” We can do whatever it takes. pic.twitter.com/FPPIJsxXMa

— Stephanie Kelton (@StephanieKelton) March 27, 2020

In the early phase of the pandemic, almost no one pointed a finger at the mounting fiscal deficit or the rise in the (so-called) national debt. Headlines like this one, proclaiming that we are all MMTers now, became commonplace. It started to feel like we might actually have an honest conversation about the limits to government spending.1

But now we are backsliding.

The debt ceiling fight has brought renewed attention to the anticipated path of future spending relative to income. The annual deficit already exceeds $1 trillion, and it is expected to rise sharply (for a variety of reasons, including the Federal Reserve’s hiking of interest rates) in the coming years.

Instead of opening up an honest dialogue about what this all means (and doesn’t mean) for the lives of everyday people, it’s back to finger-pointing.

We can go down this path for another half-century, trading barbs like, “Republicans only care about deficits when a Democrat is in the White House.” Or we can stop it and finally have an honest conversation.

How refreshing would it be to turn on the TV and find a member of Congress flipping the script? Pressed to share their ideas about how do deal with America’s “ballooning debt problem,” imagine hearing them riff from these talking points:

There is no debt crisis. Not today and not on the horizon.

The national debt poses no risk to our nation’s finances.

The so-called “debt” is just the dollars we spent but didn’t tax back.

It’s part of the broader US money supply.

It will not leave future generations with a lower standard of living or a crushing burden of debt and taxes.

It is nothing like running up your personal credit card.

We do not eventually need to “pay it off.”

That’s not a comprehensive list—feel free to add your own in the comments—and lawmakers would obviously need to be well equipped to defend each statement. It would take hard work, but it can be done!

How do I know? Because the (now former) Chairman of the House Budget Committee, John Yarmuth, has done it.

In Closing

There’s another reason why the finger-pointing is so frustrating. While democrats and republicans blame one another for “blowing up the deficit” with tax cuts, unfunded wars, spending on social programs, etc., the truth is that so much of what happens really just depends on the state of our economy.2

As MMT economist Eric Tymoigne shows in this recent article, deficits shrink in a booming economy (mostly because a progressive tax code substantially boosts tax revenue). Over time, if the deficit gets too small to support the private credit structure, it chokes off the boom. Unless something happens to recharge aggregate demand, the slowdown can evolve into recession. When that happens, the automatic stabilizersswing the other way, moving the deficit higher.

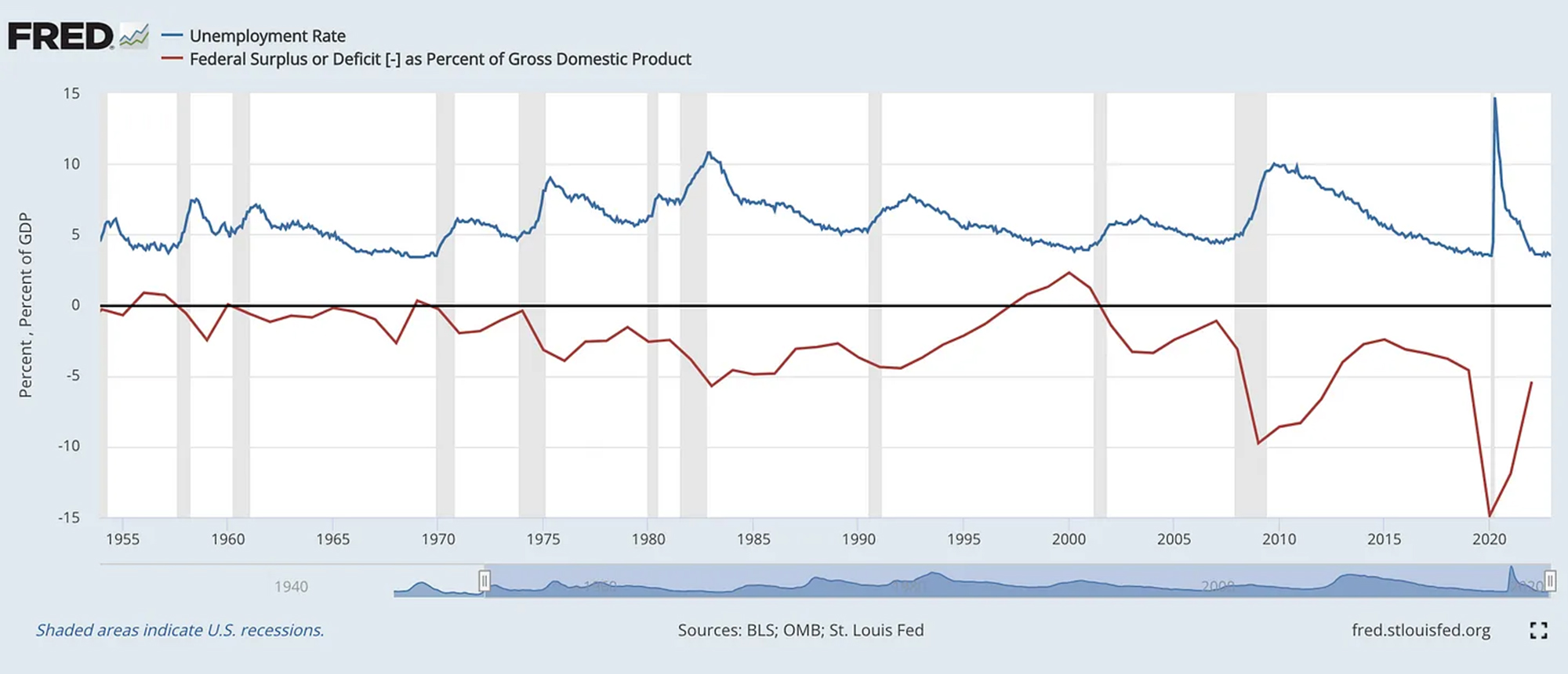

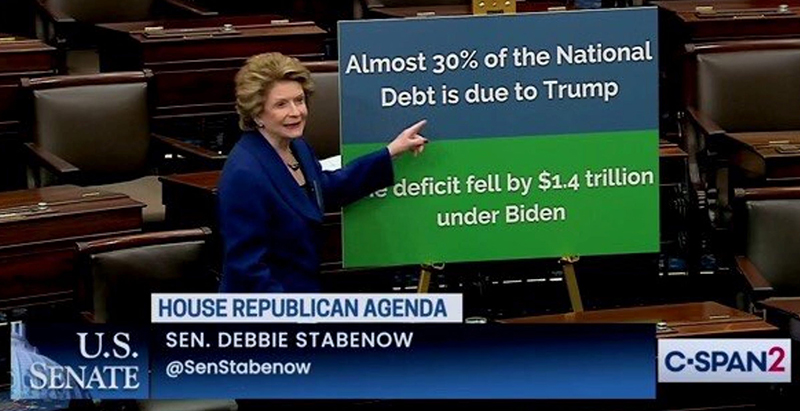

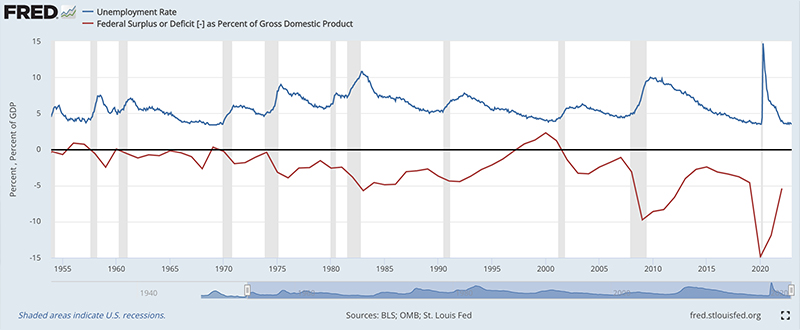

You can see this clearly in the data. When the unemployment rate is rising (blue line), the government budget tends to move more deeply into deficit (red line). Over the last year, the opposite happened. As President Biden likes to remind us, the fiscal deficit shrank from $2.6T to $1.4T last year. That was, in part, due to the ongoing economic recovery.

But what happens if the recovery falters, as most economists anticipate, sometime this year?

I would suggest that Democrats should be particularly cautious with the finger-pointing right now. Setting aside the fact that their rhetoric reinforces dangerous myths about the government’s finances, they should think about whether all of this bragging about shrinking the deficit is going to serve them well if/when the US economy tips into recession ahead of the next election. If that happens, then there’s a good chance the deficit will be increasing as we head into 2024.

So let’s stop the finger-pointing and improve the conversation. Here’s another talking point to get us started.

1- At its core, MMT is about replacing an artificial/imaginary/phony budget constraint with a real resource/inflation constraint.

2- In MMT parlance, it is driven by the net savings desires of the non-government sector.