The Need For Public Housing

Origins of Public Housing in the United States

Amidst widespread poverty and unemployment of the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt embarked on a mission to integrate publicly built affordable housing into his economic recovery plan, the New Deal. One of the most impactful elements of the New Deal was the Public Works Administration, an unprecedented mobilization of public resources to provide jobs and critical infrastructure to the American people and pull the nation out of a crippling depression. One of the longest lasting legacies of the PWA still stands today— public housing.

Throughout the course of the New Deal, the PWA provided over $6 billion, roughly $126.6 billion today, in funding for infrastructure projects including public housing, allowing public housing developments to expand across the country. The federal government aided municipal and state governments to form housing authorities tasked with building, administering, and maintaining the nation’s public housing stock, with nearly one million units still in existence today. A third of our nation’s public housing stock is in just ten of the country’s major cities including New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Miami. Though wildly successful at building affordable units for over a million Americans, the legacy of public housing lives under the long shadow of America’s racial segregation with many developments housing separated and segregated communities.

In 1937, legislation was enacted placing price caps on government expenditures per unit, leading to the decline in quality of public housing as well as middle class residents in public housing.

A Promise Betrayed

Following World War II, Roosevelt’s successor, President Harry Truman changed course, re-orienting the government’s housing policy from mass subsidization of public housing to the controversial urban renewal program, a public-private partnership in which the government cleared blighted neighborhoods to pave the way for private developers to build homes and start businesses. Throughout the course of urban renewal, only one home was built for every four that were razed, marking an era of mass displacement and privatization. Moreover, the growing stigmatization of public housing as concentrated pockets of poverty led to a backlash, with states such as California enacting legislation to block further public housing development.

In 1965, the Housing and Urban Development Act was passed, creating the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which administers the country’s public housing and funding for affordable housing. The HUD Act introduced the first rental subsidy program funded by the federal government, marking a major policy shift with the government shifting the responsibility of affordable housing production and maintenance on private developers and landlords.

The rental subsidy program was enshrined as the central policy to boost housing affordability with the creation of the Section 8 housing choice vouchers in 1974, with Section 8 recipients paying 30% of their income toward rent and HUD vouchers paying for the difference between the market rate and tenants’ income-capped rent. Yet the market-based solution has allowed patterns of segregation as landlords discriminatorily refuse Section 8 vouchers to prevent lower-income residents, particularly people of color, to move into historically exclusionary neighborhoods.

Three years later, the Housing Act of 1968 banned high rise public housing development and accelerated white flight by reallocating funding to subsidize the purchase of single family homes outside the urban core, placing a larger share of maintenance on cities and states rather than the federal government. In doing so, America’s public housing system entered a constant cycle of disinvestment— rents collected from tenants were insufficient to properly fund the maintenance of our public housing buildings and most of our public housing stock fell into disrepair.

In 1973, Nixon ordered a moratorium on federal [1][2]aid for housing and community development. The subsequent three administrations, Reagan, Bush and Clinton, slashed HUD’s public housing funding by over 50%.

Successful Public Housing Models

Meanwhile, there are successful public housing models in cities and countries around the world, most notably Vienna, Austria and Singapore.

The city of Vienna is home to 220,000 units of publicly owned housing, roughly 25% of the city’s overall market. In addition, the city has permitted private developers to build 200,000 units on publicly owned land, negotiating terms to ensure price controls and affordability requirements.1 Close to 60% of its residents live in public housing and units are capped at 20-25% of a resident’s income. For over a century, Vienna has led and expanded its public housing portfolio with strong public support. In contrast to the United States where there is rigid means testing for subsidized housing, Viennese public housing units permit residents to stay in their units even if their income grows above the unit’s intended threshold allowing families to establish roots in a mixed income community with a stable and affordable home.

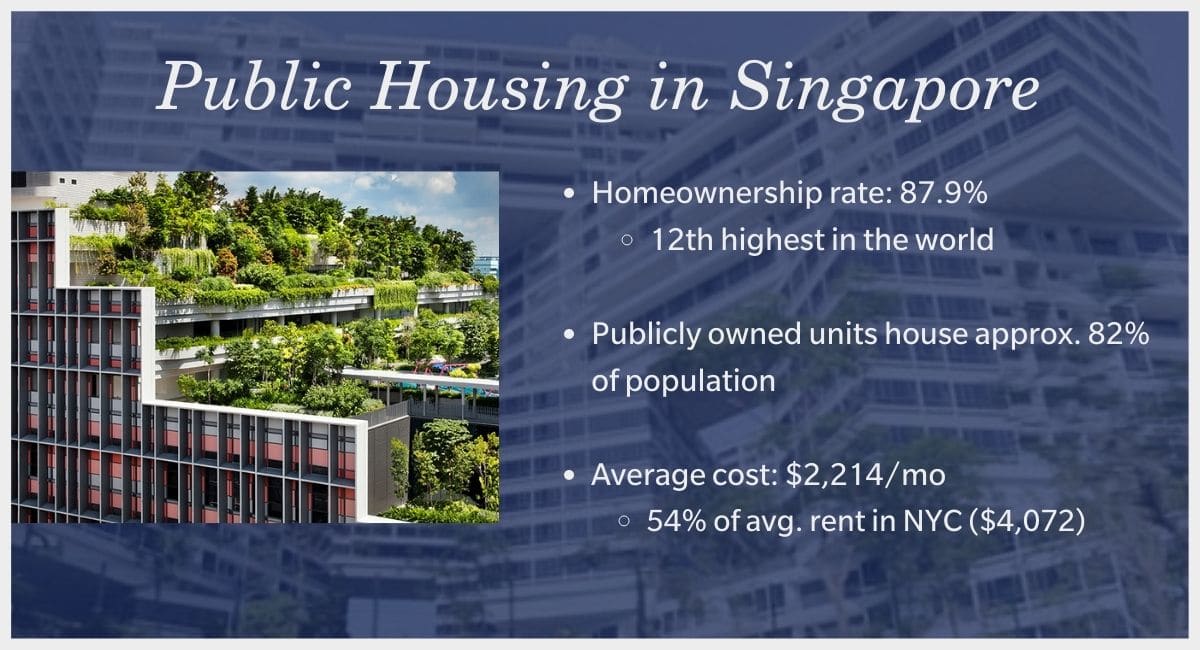

Singapore is another well cited example of public housing. Though different from the American and Austrian models, Singapore houses 82% of its population in public housing built by the Housing Development Board (HDB). In addition, approximately 90% of HDB residents own their apartments, allowing virtually all Singaporean residents an accessible and affordable path to homeownership.

Where Do We Go Now?

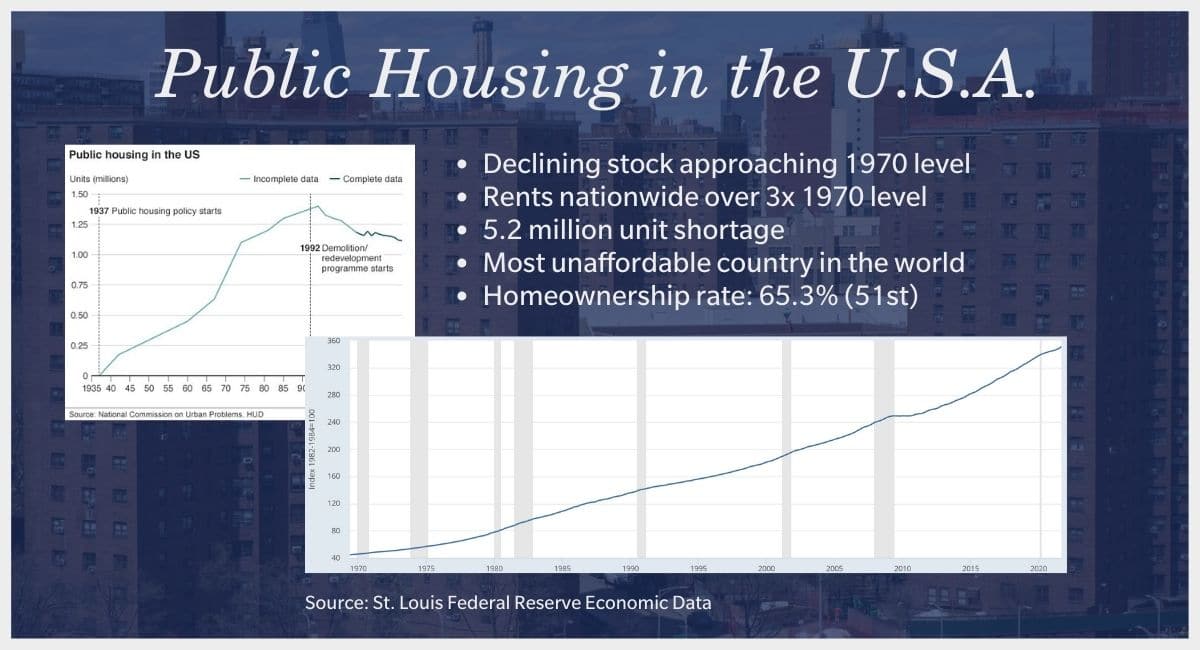

America is facing a devastating affordable housing crisis, with record rates of homelessness. The importance of maintaining existing and constructing new public housing units is re-entering the public policy discourse again.

There are over two million Americans living in public housing– 70% are people of color, 16% are seniors and 36% are disabled people. There are millions more who qualify for public housing units but are unable to secure a home due to shortage of units and lack of resources and support to navigate the system. Housing experts agree that a deep investment in maintenance and construction of public housing units will not only make a significant impact on addressing our national homelessness crisis but spur economic growth by providing financial stability and security to millions of American households.

First, we must adequately fund local and state housing authorities to adequately maintain and retrofit our existing public housing stock. Cities are at risk of continuing to lose precious units of our affordable housing to disrepair, mismanagement and neglect. In 2019, Senator Bernie Sanders and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez introduced the Green New Deal for Public Housing bill, which would provide a historic $180 billion to both repair and sustainably retrofit our 950,000 public housing units nationwide over the next ten years. This bill would create up to 240,000 union jobs per year while reducing our annual carbon emissions by roughly 5.6 million metric tons, the equivalent of taking over 1.2 million cars off the road.

Second, we must invest in public housing neighborhoods to improve conditions surrounding public housing and improve services on-site to improve safety, wellness and resiliency of residents.

Third, we can fund the replacement of public housing units lost in the past, under the Faircloth Act limit, growing the existing supply of affordable homes in our nation.

As the shortage of affordable housing units continues to worsen every year, reaching a deficit of 5.2 million units this year, it’s clear that market-based solutions alone have not built the housing needed by millions of Americans. Reinvesting in public housing is a part of the solution and should be a part of our strategy in housing every American.

To learn more about public housing in America and abroad, visit these resources:

https://berniesanders.com/issues/housing-all/

https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/21/bernie-aoc-public-housing-plan-484013

https://www.politico.com/news/2021/11/10/schumer-billions-new-york-public-housing-520519

American Public Housing:

Goetz, Edward. “Gentrification in Black and White: The Racial Impact of Public Housing Demolition in American Cities.” Urban Studies 48, no. 8 (2011): 1581–1604. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43081801.

Ruechel, Frank. “New Deal Public Housing, Urban Poverty, and Jim Crow: Techwood and University Homes in Atlanta.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 81, no. 4 (1997): 915–37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40550189.

Bloom, Nicholas Dagen. “Public Housing That Worked: New York in the Twentieth Century.” (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008).

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/06/section-8-is-failing/396650/

https://time.com/5826392/coronavirus-housing-history/

Vienna Public Housing:

“Housing as a basic human right:” The Vienna Model of Social Housing

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr_edge_featd_article_011314.html

Singaporean Public Housing:

https://www.economist.com/asia/2017/07/06/why-80-of-singaporeans-live-in-government-built-flats

Eng, Teo Siew, and Lily Kong. “Public Housing in Singapore: Interpreting ‘Quality’ in the 1990s.” Urban Studies 34, no. 3 (1997): 441–52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43083375.

Yuen, Belinda. “Reinventing Highrise Housing in Singapore.” Cityscape 11, no. 1 (2009): 3–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20868687