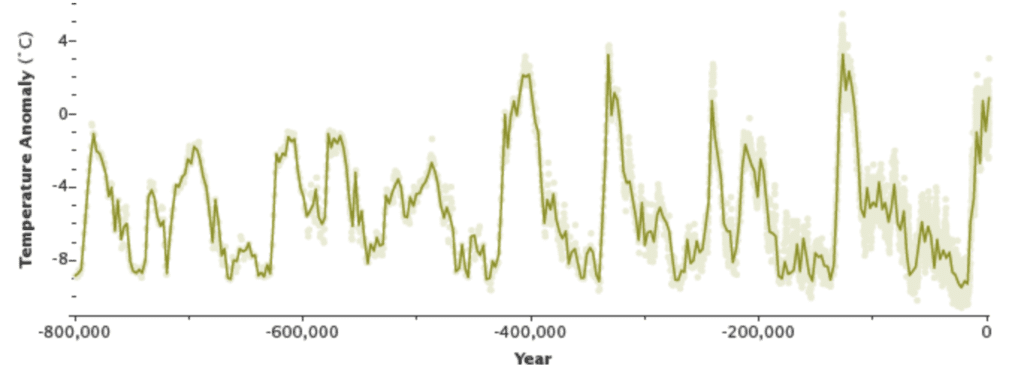

Earth has experienced climate change in the past without help from humanity. We know about past climates because of evidence left in tree rings, layers of ice in glaciers, ocean sediments, coral reefs, and layers of sedimentary rocks. For example, bubbles of air in glacial ice trap tiny samples of Earth’s atmosphere, giving scientists a history of greenhouse gases that stretches back more than 800,000 years. The chemical make-up of the ice provides clues to the average global temperature.

Earth has cycled between ice ages (low points, large negative anomalies) and warm interglacials (peaks). (NASA graph by Robert Simmon, based on data from Jouzel et al., 2007.)

Using this ancient evidence, scientists have built a record of Earth’s past climates, or “paleoclimates.” The paleoclimate record combined with global models shows past ice ages as well as periods even warmer than today. But the paleoclimate record also reveals that the current climatic warming is occurring much more rapidly than past warming events.

As the Earth moved out of ice ages over the past million years, the global temperature rose a total of 4 to 7 degrees Celsius over about 5,000 years. In the past century alone, the temperature has climbed 0.7 degrees Celsius, roughly ten times faster than the average rate of ice-age-recovery warming.

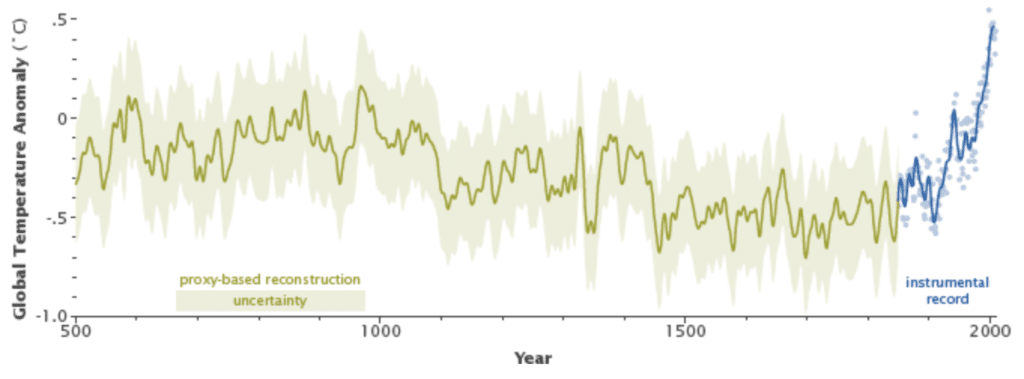

Temperature histories from paleoclimate data (green line) compared to the history based on modern instruments (blue line) suggest that global temperature is warmer now than it has been in the past 1,000 years, and possibly longer. (Graph adapted from Mann et al., 2008.)

Models predict that Earth will warm between 2 and 6 degrees Celsius in the next century. When global warming has happened at various times in the past two million years, it has taken the planet about 5,000 years to warm 5 degrees. The predicted rate of warming for the next century is at least 20 times faster. This rate of change is extremely unusual.