As Democrats on Capitol Hill and the campaign trail present an array of ambitious and expensive policy proposals, from a Green New Deal to Medicare for All, the question they face most often is, “How will the government pay for it?”

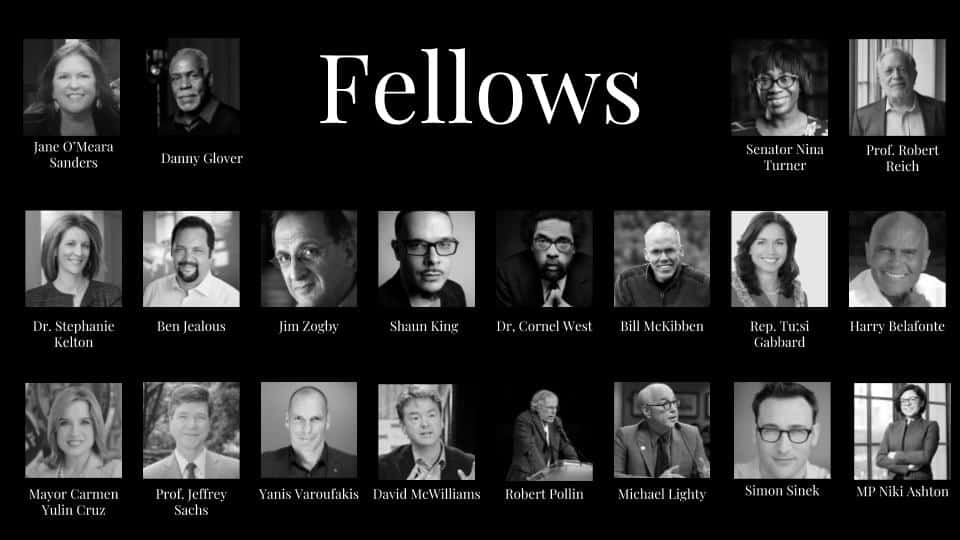

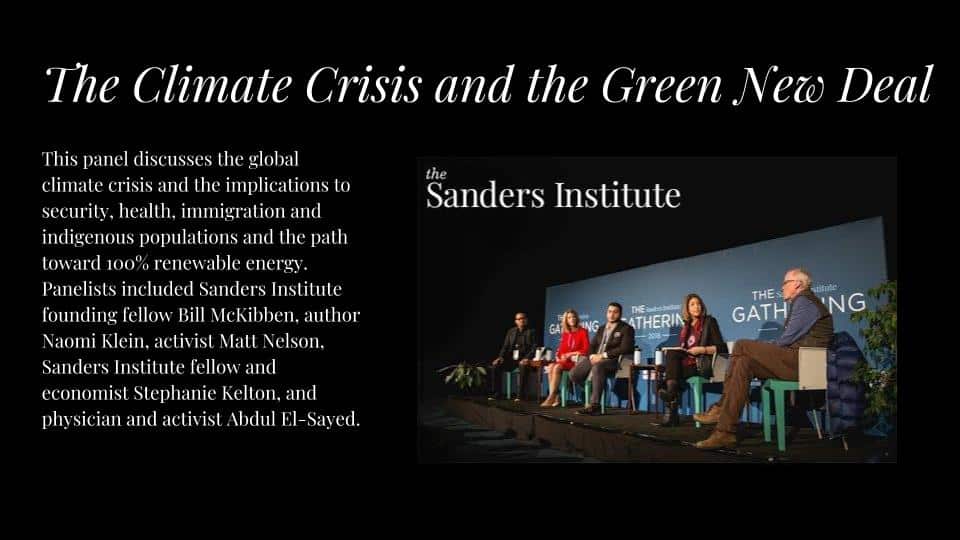

The answer, increasingly, comes from a professor at Stony Brook University on Long Island, Stephanie Kelton, who has become the public face of an unorthodox strain of economics called modern monetary theory. It is pitting mainstream economists and deficit hawks against left-wing progressives.

Ms. Kelton argues the government doesn’t need to worry so much about how much it borrows to pay for spending programs. Unlike a household or business, it can never run out of money. The government can always print money to pay for debts. The constraint, according to MMT, isn’t the deficit, but whether the borrowing and spending spurs inflation and disrupts economic activity.

With inflation and interest rates now very low, the government has plenty of room to borrow and spend more, MMT advocates say. The notion has gained traction among Democratic presidential hopefuls, helping to fuel ambitious policy proposals.

“If you were being responsible, you’d want to approve new spending not because you can demonstrate that it won’t add to the deficit, but because you can demonstrate that it won’t create dislocation, inflationary pressure—real problems in the economy,” Ms. Kelton said in an interview.

The theory, which Ms. Kelton helped establish in the late 1990s, has gotten approving nods from Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, the Democratic presidential contender whom she advised in 2016, and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D., N.Y.).

The rise of MMT comes as mainstream economists are reconsidering the danger of deficits. Former International Monetary Fund chief economist Olivier Blanchard, former Council of Economic Advisers chairman Jason Furman and Harvard University economics professor Kenneth Rogoff have all said recently the U.S. appears to have more room to borrow than they once thought.

Republicans, too, have backed away from past opposition to large deficits. With Republicans in control of the White House and Congress in 2017 and 2018, deficits marched toward $1 trillion, in part because of tax cuts and increased military spending.

The deficit totaled 4.5% of economic output last year, compared with an average of 2.9% over the previous 50 years. Debt-to-GDP has more than doubled, from 35% at the end of 2007 to 78% by the end of 2018, and is on track to hit 93% by 2029.

“MMT has been standing with its feet in the same spot for decades,” Ms. Kelton said. “The mainstream economists keep inching, inching, a little bit closer. It’s something we’ve been watching for a very long time.”

Ms. Kelton is everywhere these days—on cable television and public radio, penning opinion columns and keynoting financial industry conferences. She has a book on MMT being released in April 2020.

Still, many mainstream economists on the left and right say MMT takes the idea of deficit spending too far.

In a survey by the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business of 38 mainstream academic economists, 88% disagreed or strongly disagreed that countries that borrow in their own currency don’t need to worry about deficits.

The critics say MMT will lead to the very outcome Ms. Kelton and other proponents says it is designed to avoid: surging inflation and interest rates. They also say rising government spending will crowd out more productive private investment.

“How much more debt can you have on the U.S. balance sheet and not have global financial markets react? I don’t know the answer to that,” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, a right-leaning think tank, and former Congressional Budget Office director. “I see no reason to run the experiment, ‘When do we have a crisis?’ Let’s just not.”

Mainstream economists say the government must tax businesses and households to pay for spending. Whatever it doesn’t raise through taxes it borrows by issuing bonds.

MMT rejects this as backward. Spending isn’t constrained by the government’s ability to raise taxes or borrow, because the government can always create more money to fund itself. The real constraint on spending is the ability of the economy to absorb new spending without creating shortages and inflation.

In this worldview, fiscal and monetary policy are more tightly intertwined than in conventional economics. The central bank could accept IOUs from the Treasury to fund new spending—a step it can’t necessarily take under current law—and inflation can be tamed by fiscal policy makers by raising taxes, cutting spending or imposing new regulations. Critics say it is politically impractical and the central bank is best left to manage inflation independently, as it is called on to do in all advanced economies today.

Some of Ms. Kelton’s toughest criticism has come from the left. Some say more government spending is justified now because interest rates are low and would help facilitate it, but they see MMT as the wrong framework for justifying such action.

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, a Democrat, in a Foreign Affairs article panned MMT as a ”poor guide to policy in normal economic times.” When Paul Krugman, a Nobel Prize winner in economics and a liberal columnist for the New York Times, tweeted last month, “Still don’t see what we get out of it,” referring to MMT, Ms. Kelton shot back, “How about a superior analytic framework and better predictive record (20+ years running) than any other macro approach.”

She continues to advise the senator on a plan for a federal jobs guarantee, though she hasn’t formally joined any 2020 presidential campaign.

“I don’t feel like just because we’re staring down trillion-dollar deficits we’re out of room and Congress can’t be considering ambitious spending,” she said, predicting the debt-to-GDP ratio could easily reach 150% without causing problems for the economy.