Though Barack Obama presided over a recovery from the 2008 economic recession, the economic benefits disproportionately went to the wealthiest top 10 percent of Americans.

Though Democrats point to the job creation and low unemployment rate Obama passed onto Trump as an indication that Obama’s economic policies, the status quo, needed no revisions, that “America is already great,” in reality the benefits of this economy and the experiences under it weren’t felt by large demographics of Americans in the working, middle and low income classes. These persistent economic anxieties, coupled with an anti-political climate incited by the establishment corrupting American politics through massive corporate lobbying and campaign donations, enabled the rise of Donald Trump.

All early signs of Trump’s Administration have made it clear, through filling his cabinet with billionaires and Wall Street bankers, that he has no intention to representing or improving the lives of working, middle class, or low income Americans. Promises to “drain the swamp” have been broken with filling of the swamp with even more wealthy and establishment elites. Even without enacting any policy or legislation to help those in economic need, the continued economic recovery may help Trump feign the appearance of helping these demographics, but as Bernie Sanders Former Chief Economic Advisor Stephanie Kelton, a Professor of Economics at University of Missouri-Kansas City, notes in a recent paper, there may be no more room for economic recovery given the economy has reached its true employment potential, or as Kelton puts it, ” output is near its full employment ceiling not because the economy rose to its potential but because we lowered the definition of what we believe our nation’s productive capacity to be. It’s a bit like giving up on the idea that your child is capable of achieving straight As, relaxing the goal to a 2.0 GPA, and then celebrating when he presents you with across-the-board Cs.”

Kelton compared the current output gap with the 2007 estimate of potential GDP, which indicates based on previous definitions of America’s productive capacity that the current GDP gap would be close to 14 percent and not closer to zero. She cites several economist who have noted that the U.S. labor market is still far from full employment, though its unclear if Trumponomics will squeeze out more growth from the economy because, “less than three months into the Trump presidency, there is no formal budget and no precise blueprint that describes the full range of policies and programs that the administration intends to pursue.” Despite this, an economic agenda is beginning to take shape, one that is likely to center around massive spending cuts to compensate for increases in defense spending.

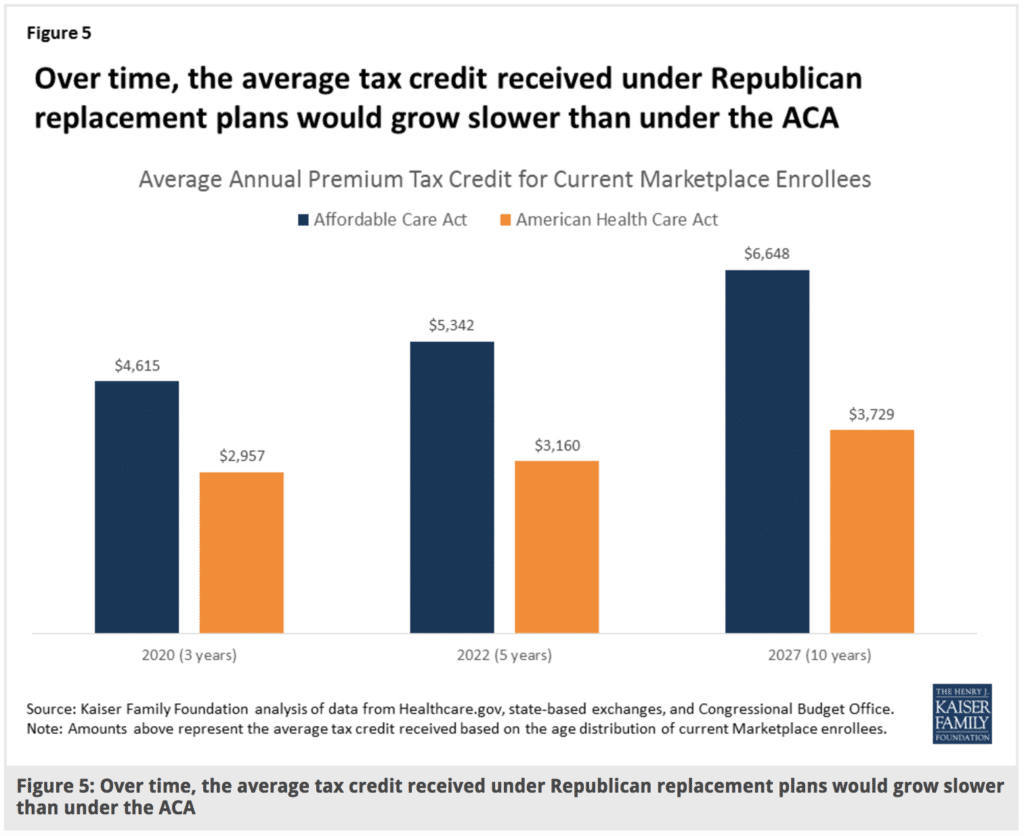

Like Reagan, massive spending cuts and an economic agenda predicated on increasing the wealth and income of the top 1 percent resulted in economic growth, and helped Reagan get re-elected in a landslide. Trump’s Administration is shaping to be similar in its pro-business model that will provide gains to wealthy who have aligned with the Trump Administration and filled his cabinet. Already Trump has promised massive tax cuts for the rich, and the Obamacare repeal effort will provide even more tax cuts to the wealthy. Kelton added, “taken together, Trumponomics includes a hefty serving of Reagan-inspired trickledown economics along with a side of protectionism, a dash of military Keynesianism and a social agenda that is anti-worker and anti-immigrant.”

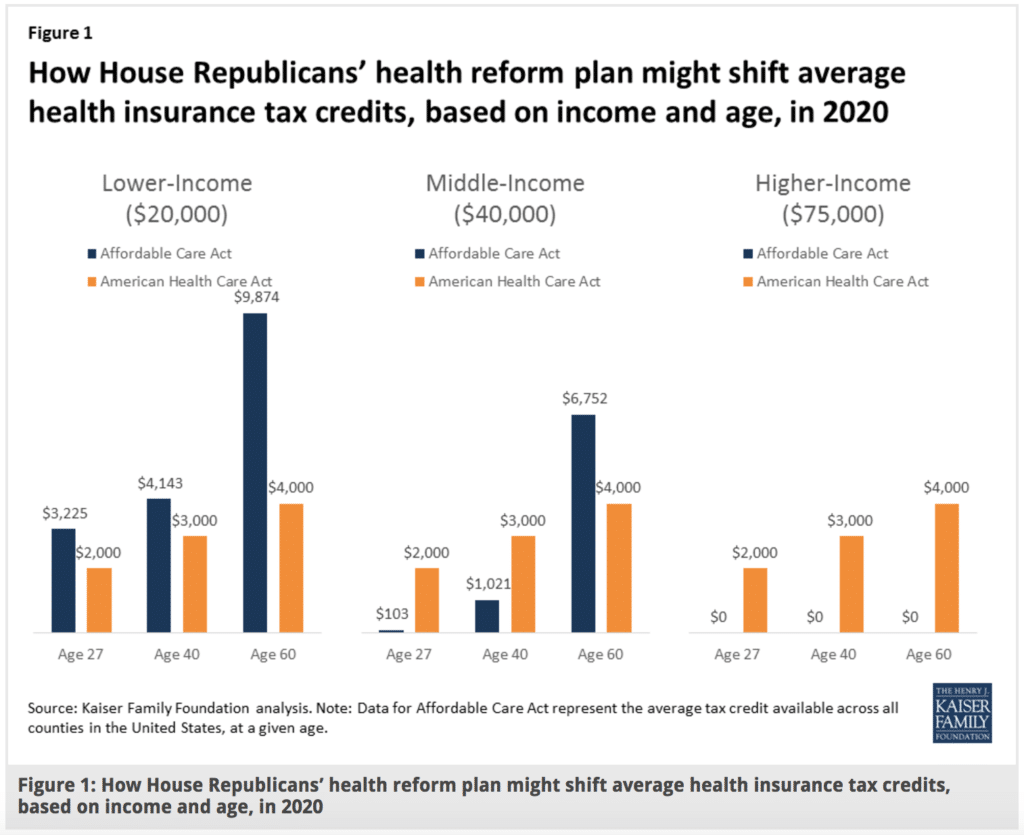

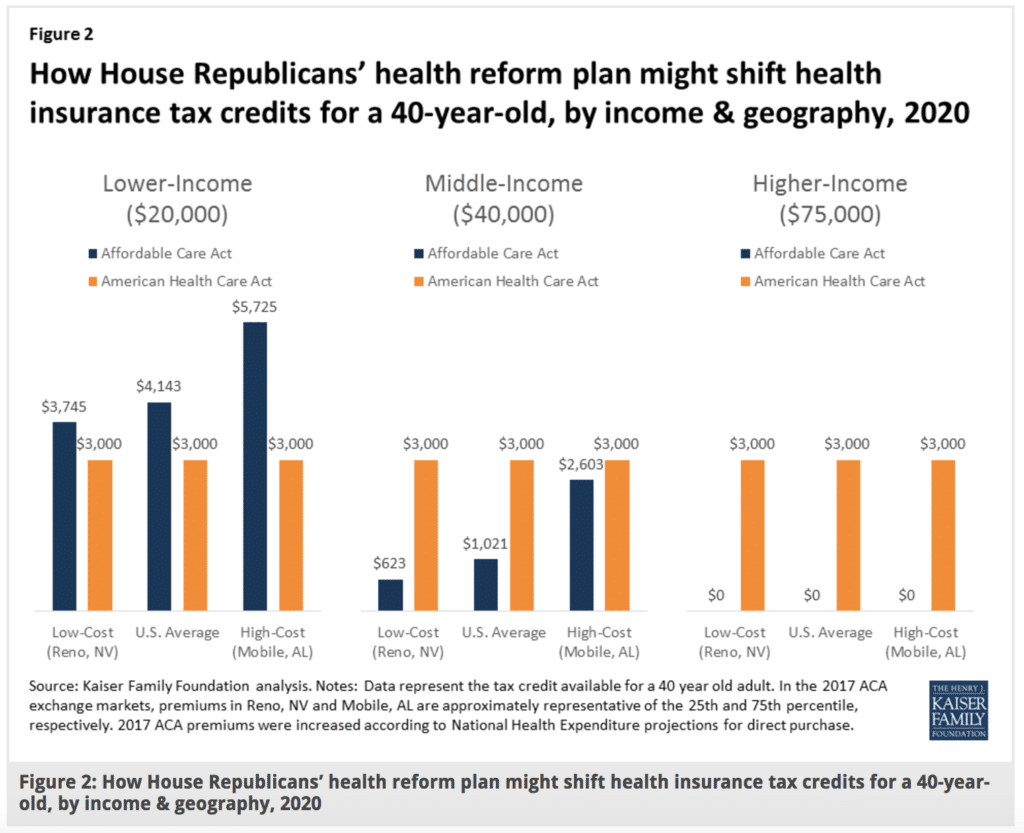

Trump’s promises to “Make America Great Again” come up far short in every simulation conducted by Goldman Sachs and Moody’s, Though an economic doomsday scenario may not result immediately from Trumponomics, with some initial growth possible, Trump’s economic policies will be a disaster for the sick, working, middle class, and low income Americans.