For the sake of keeping things manageable, let’s confine the discussion to a single continent and a single week: North America over the last seven days.

In Houston they got down to the hard and unromantic work of recovery from what economists announced was probably the most expensive storm in US history, and which weather analysts confirmed was certainly the greatest rainfall event ever measured in the country – across much of its spread it was a once-in-25,000-years storm, meaning 12 times past the birth of Christ; in isolated spots it was a once-in-500,000-years storm, which means back when we lived in trees. Meanwhile, San Francisco not only beat its all-time high temperature record, it crushed it by 3F, which should be pretty much statistically impossible in a place with 150 years (that’s 55,000 days) of record-keeping.

That same hot weather broke records up and down the west coast, except in those places where a pall of smoke from immense forest fires kept the sun shaded – after a forest fire somehow managed to jump the mighty Columbia river from Oregon into Washington, residents of the Pacific Northwest reported that the ash was falling so thickly from the skies that it reminded them of the day Mount St Helens erupted in 1980.

That same heat, just a little farther inland, was causing a “flash drought” across the country’s wheat belt of North Dakota and Montana – the evaporation from record temperatures had shrivelled grain on the stalk to the point where some farmers weren’t bothering to harvest at all. In the Atlantic, of course, Irma was barrelling across the islands of the Caribbean (“It’s like someone with a lawnmower from the sky has gone over the island,” said one astounded resident of St Maarten). The storm, the first category five to hit Cuba in a hundred years, is currently battering the west coast of Florida after setting a record for the lowest barometric pressure ever measured in the Keys, and could easily break the 10-day-old record for economic catastrophe set by Harvey; it’s definitely changed the psychology of life in Florida for decades to come.

Oh, and while Irma spun, Hurricane Jose followed in its wake as a major hurricane, while in the Gulf of Mexico, Katia spun up into a frightening storm of her own, before crashing into the Mexican mainland almost directly across the peninsula from the spot where the strongest earthquake in 100 years had taken dozens of lives.

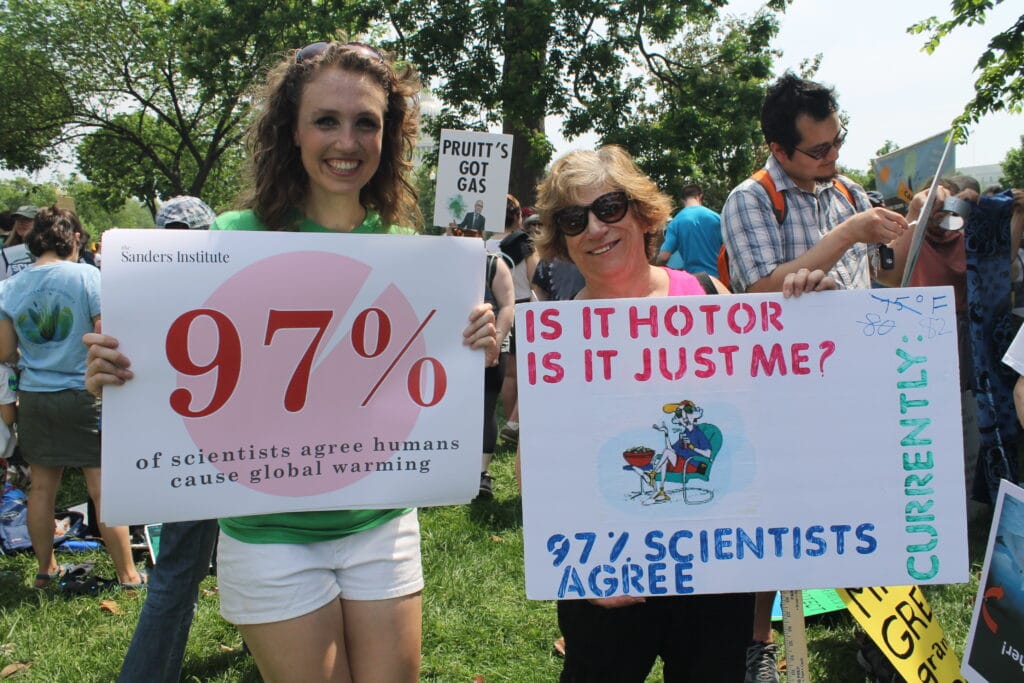

Leaving aside the earthquake, every one of these events jibes with what scientists and environmentalists have spent 30 fruitless years telling us to expect from global warming. (There’s actually fairly convincing evidence that climate change is triggering more seismic activity, but there’s no need to egg the pudding.)

That one long screed of news from one continent in one week (which could be written about many other continents and many other weeks – just check out the recent flooding in south Asia for instance) is a precise, pixelated portrait of a heating world. Because we have burned so much oil and gas and coal, we have put huge clouds of CO2 and methane in the air; because the structure of those molecules traps heat the planet has warmed; because the planet has warmed we can get heavier rainfalls, stronger winds, drier forests and fields. It’s not mysterious, not in any way. It’s not a run of bad luck. It’s not Donald Trump (though he’s obviously not helping). It’s not hellfire sent to punish us. It’s physics.

Maybe it was too much to expect that scientists’ warnings would really move people. (I mean, I wrote The End of Nature, the first book about all this 28 years ago this week, when I was 28 – and when my theory was still: “People will read my book, and then they will change.”) Maybe it’s like all the health warnings that you should eat fewer chips and drink less soda, which, to judge by belt-size, not many of us pay much mind. Until, maybe, you go to the doctor and he says: “Whoa, you’re in trouble.” Not “keep eating junk and some day you’ll be in trouble”, but: “You’re in trouble right now, today. As in, it looks to me like you’ve already had a small stroke or two.” Hurricanes Harvey and Irma are the equivalent of one of those transient ischaemic attacks – yeah, your face is drooping oddly on the left, but you can continue. Maybe. If you start taking your pills, eating right, exercising, getting your act together.

That’s the stage we’re at now – not the warning on the side of the pack, but the hacking cough that brings up blood. But what happens if you keep smoking? You get worse, till past a certain point you’re not continuing. We’ve increased the temperature of the Earth a little more than 1C so far, which has been enough extra heat to account for the horrors we’re currently witnessing. And with the momentum built into the system, we’re going to go somewhere near 2C, no matter what we do. That will be considerably worse than where we are now, but maybe it will be expensively endurable.

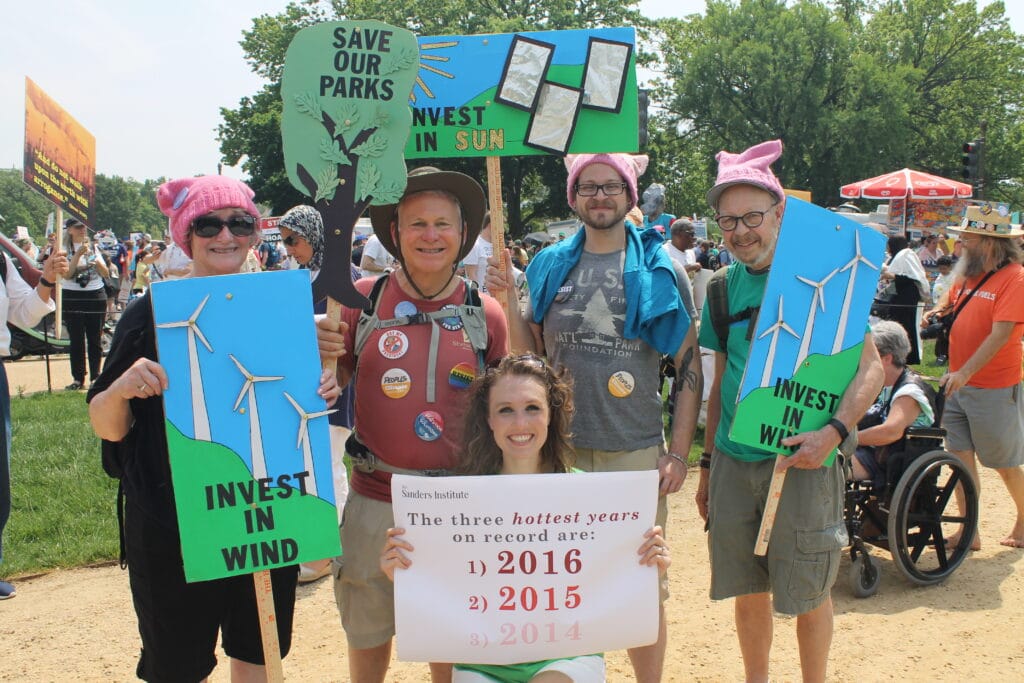

The problem is, our current business-as-usual trajectory takes us to a world that’s about 3.5C warmer. That is to say, even if we kept the promises we made at Paris (which Trump has already, of course, repudiated) we’re going to build a planet so hot that we can’t have civilisations. We have to seize the moment we’re in right now – the moment when we’re scared and vulnerable – and use it to dramatically reorient ourselves. The last three years have each broken the record for the hottest year ever measured – they’re a red flashing sign that says: “Snap out of it.” Not bend the trajectory somewhat, as the Paris accords envisioned, but simultaneously jam on the fossil fuel brakes and stand on the solar accelerator (and also find some metaphors that don’t rely on internal combustion).

We could do it. It’s not technologically impossible – study after study has shown we can get to 100% renewables at a manageable cost, more manageable all the time, since the price of solar panels and windmills keeps plummeting. Elon Musk is showing you can churn out electric cars with ever-lower sticker shock. In remote corners of Africa and Asia, peasants have begun leapfrogging past fossil fuel and going straight to the sun. The Danes just sold their last oil company and used the cash to build more windmills. There are just enough examples to make despair seem like the cowardly dodge it is. But everyone everywhere would have to move with similar speed, because this is in fact a race against time. Global warming is the first crisis that comes with a limit – solve it soon or don’t solve it. Winning slowly is just a different way of losing.

Winning fast enough to matter would mean, above all, standing up to the fossil fuel industry, so far the most powerful force on Earth. It would mean postponing other human enterprises and diverting other spending. That is, it would mean going on a war-like footing: not shooting at enemies, but focusing in the way that peoples and nations usually only focus when someone’s shooting at them. And something is. What do you think it means when your forests are on fire, your streets are underwater, and your buildings are collapsing?