As the GOP tax plan, officially known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, awaits reconciliation with the House, the threat of a mounting deficit is once again in the news.

According to the bipartisan Joint Committee on Taxation and the Congressional Budget Office, the tax plan will add roughly $1 trillion to the deficit over the next ten years—almost enough money to abolish student loan debt ($1.4 trillion). Democrats, who in the past two decades have grown increasingly cautious about federal spending, were quick to note the hypocrisy of the even more hawkish Republican party. What happened to protecting our children from the crushing burden of the national debt?

But while there are many things to fear in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—a windfall for the rich at the expense of the poor, permission to drill in a wildlife refuge—the growing deficit should not be one of them. On the contrary, obsessing over the deficit could further imperil those whom the tax bill leaves worst off. In this interview, Stephanie Kelton, a professor of economics at Stony Brook University and former economic advisor to Bernie Sanders, explains why.

You recently shared a video in which you explain what the federal budget deficit is and what it’s not. I was hoping you could elaborate on that: How does the deficit differ from what people think it is?

It would be easier to answer if we could figure out what people think it is, so let’s start there. I think the most accurate way to portray it is that people think deficits are bad because they think they’re evidence that the government is overspending. In fact, when I served on the US Senate Budget Committee as the chief economist for the Democrats, I sat through many, many hearings called by the majority where the chairman, Senator Mike Enzi, would repeat variations on that phrase: “a deficit is evidence of overspending.”

I’d sit in the backbenches behind Senator Sanders and just kind of shake my head. Because as all economists know, a deficit isn’t evidence of overspending, inflation is evidence of overspending. A deficit is just evidence that the government put more money into the economy than it took out.

In the video, I try to explain it with very simple numbers. Say the government puts $100 into the economy and takes $90 out. The government’s books will show a deficit of $10. If the government spends more than it takes out in a given period of time, say a fiscal year, it’s recorded as a government deficit. OK. But what about the rest of the books in the economy? If all we do is focus on the government’s ledger, we’re looking at the picture with one eye shut. What people should understand is that when the government runs a deficit, it’s adding dollars to the economy. Somebody gets those dollars. If the government adds $100 and only takes back $90, somebody in the economy ends up with $10 they wouldn’t have had otherwise.

The real question to ask is: Why did the government run the deficit? What was it trying to achieve? Was it the product of spending to repair crumbling infrastructure, or to better fund schools, or to give greater aid to the sick and the poor? Or if the deficit increased because the government cut taxes, why did they do that? To lift the incomes of households that haven’t seen real wage gains for many decades? Once you know, you can at least have a conversation: “Well, that’s where the money went.” But to just look at the deficit and say that it’s good or bad without any further information is crazy.

Of course, that’s what we all do. We judge the government’s behavior as if smaller deficits are by definition good, bigger deficits are by definition bad, and a balanced budget is by definition the goal. All of that, in my view, is just getting it wrong.

One point of confusion is where the money for the federal budget comes from. Most people assume the US government runs on taxpayer dollars, because that’s how it works on the state level: local schools are paid for by taxpayers, et cetera. But you’ve written before that unlike individuals or local governments, the federal government doesn’t need to “get” money from anywhere before it can spend it. Can you say more about the difference?

It is absolutely true that states, municipalities, and local governments depend on tax revenue in order to fund themselves. It is absolutely untrue that the federal government of the United States depends on tax revenue to fund itself. The United States government is the issuer of our currency—the US dollar. It has to spend dollars before the rest of us can get any. Households, local governments, private businesses, state governments—they are all users of the dollar. They have to get dollars in order to spend them. That’s the big difference.

Not only do people tend to think of the government like a household—believing it can’t go on spending more than it takes in, taking on more and more debt and never paying off all its debt—they also assume they can draw parallels between the federal budget and a state budget. For example, many people who should and probably do know better have used Kansas to argue that massive tax cuts will leave the federal government without the revenue it needs to operate, just as they did in the state of Kansas. Governor Brownback massively cut taxes on the advice of Arthur Laffer, Reagan’s former economic adviser, who was hired as a consultant to the Republicans and was paid a hefty sum of $75,000. The experiment did not work the way Brownback and other Republicans told voters it would. It didn’t attract companies and businesses and jobs, it didn’t create so much growth that revenues exploded. Instead it bled the coffers—because the state does need revenue from taxes to fund itself. You can’t do Reaganomics at the state level. When revenues crashed in Kansas, they ended up cutting funding for schools and other programs. It was a disaster.

You wrote in the Times that the reason to oppose the GOP tax bill is not the projected deficit but the fact that it’s a tax break for the rich. I can understand being fixated on cutting taxes as a way to lift your income, if you’re a regular person and haven’t seen any real wage growth in decades, but why would any non-rich person support this bill when it’s not even a tax break for them?

It’s kind of interesting. Anecdotally, some people have written me and said they’re talking to low-income people who are OK, actually, with the fact that most of the benefits go to those at the very top. People are saying, “Well, they are the people who hire people like me.” So the Republicans have been effective, I think, in selling this trickle-down idea that the wealthy and businesses are the real job-creators in the economy. I don’t know if that’s representative of millions of Americans or whether I’m just seeing an exception to the rule, but I am hearing, second-hand, poor people saying basically they don’t mind.

And yet there’s no good reason to believe that the people getting these tax cuts will spend in a way that creates jobs. You mentioned something in your video called “the marginal propensity to consume.” Can you explain that?

The marginal propensity to consume is the likelihood that if you get an extra margin, that extra dollar, you will spend it or spend part of it into the economy. A very poor person has an MPC of 99 percent or more: give them an extra dollar, or an extra $100, and they will spend virtually all of it, just because they’re surviving on so little. But if you give a tax break to someone like Oprah Winfrey or Bill Gates, and they get an additional dollar or $100 or $1,000, their MPC is something like 0.01 percent. They’re only going to spend a penny out of any additional $100 they get, because they already have enough to buy whatever it is they want to buy.

And when I say spend, I mean buying newly produced goods and services in the economy so that it adds to the GDP. Say you’re Jay Leno—you’re a car guy, you have lots and lots of money, and you get a windfall from these Republican tax cuts. If you go out and buy a classic Corvette convertible or whatever manufactured in the 1950s, that’s not adding to the GDP, because that car was already added to GDP the year it was first purchased. If you buy somebody else’s mansion, that doesn’t add to GDP. If you buy stocks and bonds and investments, or you buy a Picasso, that doesn’t boost GDP.

As a result of this bill, the ultra-rich—I’m talking about the one-tenth of 1 percent—will see on average about a quarter of a million dollars in additional income per year. People like Bill Gates and Oprah will get a lot more, but the average household in the one-tenth of 1 percent will see about a quarter of a million dollars. How much of that quarter million will they turn around and spend into the economy, creating demand that leads to higher sales that tell business they can produce more and hire people?

Remember a few weeks ago when John Bussey from the Wall Street Journal asked that room full of CEOs how many of them intended to create new jobs with money they’d save from the tax cuts, and only a handful raised their hands? Gary Cohn, Trump’s economic adviser, was embarrassed. He said, “Why aren’t the other hands up?” Well, the answer is that businesses don’t hire when profits go up, they hire when sales go up. That’s what drives hiring and investment. Businesses do not want to hire; the last thing they want to do is put another employee on payroll, train them, and provide them with health care. You have to make them hire. You have to swamp them with customers and create such strong demand for their product that they have no choice but to add staff.

This is where I would put the focus. The Republicans are doing the old trickle-down thing, “We’ll give the money to the people at the very top and somehow it will incentivize them to go out and start businesses in the US, or bring businesses domiciled abroad back home.” No, it won’t. The real job creators are the American consumers. It’s a shame that more consumers don’t know that: You’re the real job creator. If people have rising income, secure jobs, better pay, higher wages, they’re spending more in the economy—that’s the demand that tells these businesses it’s OK to produce more and hire more.

So in sum: it’s OK to run a deficit for good reasons; the federal government is not funded by taxpayer dollars, unlike local governments; and consumers, not rich people, create jobs. These are simple enough ideas. So why are we stuck in this austerity, trickle-down framework? Is part of the issue that Democrats also buy into it?

Exactly. Look what happened over the course of the past eight years or so. The Democrats had an opportunity to come in and really restructure things. Rahm Emanuel famously said, “you never want a serious crisis to go to waste” . . . Well, they did waste a good crisis. The economy was crashing and nearly a million people a month were losing their jobs. You lose your job you lose your income, you lose your income and guess what? You don’t pay income tax, because you can’t pay income tax on income you don’t have. Tax revenue is falling off a cliff, and spending to support the unemployed is automatically increasing. We call them the “automatic stabilizers”: unemployment compensation, food stamps, Medicaid. And so the deficit explodes.

The Obama Administration sees this happening and they panic. They say, “We have to fix it!” They turn the away from fixing the fundamental problems in the economy—away from homeowners, from joblessness—and turn their attention to the deficit. Obama famously formed the bipartisan deficit reduction commission, and thank God we didn’t do what the commission was proposing, which included entitlement reform and all kinds of stuff . . .

It seems to me that the Democrats, especially the progressive wing of the Democrats, like to repeat this talking point about how the rich aren’t paying their fair share: “The problem in this country is that the rich aren’t paying their fair share.” I don’t like that. I don’t like it because basically, it says that income is flowing up to the rich and our job is to take some of it away from them. I prefer to say: the problem is not that the wealthy don’t pay their fair share, the problem is that they’re taking more than their fair share—that’s why they’re so damn rich. That’s why real wages have stagnated for the median household for decades, because people at the top are taking more than their fair share. You don’t want to let that continue and then take back taxes and redistribute to the bottom. You want pre-distribution, not redistribution. Focus on the problem at its origin.

Americans really do believe that we should not be “punishing success.” They don’t like the idea that someone who’s worked hard and has been successful would be punished. So while a lot can be accomplished through the tax codes, there are other ways to change the distribution of wealth before anyone gets all of it.

So are politicians who fixate on the debt or the deficit lying to us about it, or do they not understand economics? I mean, Barack Obama is a smart guy. Did he not understand what was happening?

So much of it is politics. If you read some of the reports about the conversations that took place between Obama and his advisors about the stimulus—between Christina Romer [former Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers], Tim Geithner [former Treasury Secretary], and Larry Summers [former Director of the National Economic Council]—you see it. It’s clear that the economy is melting down and that it’s going to take more than simply the Fed to prevent the economy from spiraling into a depression. They start batting around these numbers, thinking, “How much do you think it’s going to take?” They had a low-end number and a high-end number. The low-end number was about $750 billion, the high end was $1.8 trillion. Christina Romer—the only female in the room—was pushing for the $1.8 trillion, and she was right. She even went down to $1.3 trillion under pressure.

This became public when Obama said, “We’re looking for something in the range of . . .” and gave these numbers. At the time, in January 2009, I was part of a panel with [former Clinton labor secretary] Bob Reich, [economist] Jamie Galbraith, and others, and we all came out and said it has to be $1.3 or trillion, at least, to keep this recession from becoming the kind that takes forever to claw our way out of.

But they didn’t listen to Romer. Larry Summers had a lot to do with it, reportedly. What I read many, many times was that he was concerned about “sticker shock.” A trillion was too big a number. People could not accept that. And he said, “We can’t do this, we can’t go to voters with a trillion.” So they settled on $787 billion. And Obama said, “our attitude is that with the legislative process, we’ll start with the low end and see what happens”—which was exactly the wrong strategy. That’s not how you negotiate. You never start with the low number.

Back to sticker shock: Why doesn’t someone like Obama just get up onstage and say, “By the way, this is how the economy works, all the economists will tell you”?

I’m pretty sure nobody’s told him. I don’t know that he understands. I don’t think Larry Summers, you know, sat him down and walked him through monetary operations. For example: two days ago, Larry Summers went on television and said, “If these tax cuts pass, the US is going to be living on a shoestring for decades to come because of the increases to the deficit that will result. We are not going to be able to defend ourselves militarily—we won’t have the ability to go to war if we need to protect ourselves.”

Now, I don’t think for a second that Larry Summers believes that. Not for a second. He’s too smart. That’s a political argument. But it’s a dangerous one. If you’re on record saying, “If the Republicans pass this bill”—which they are about to do, by the way; this bill is passing—“if the Republicans pass this bill the US will be broke,” aren’t you setting up the Republicans to then say, “Uh oh, we cut taxes and now we’re broke, we better cut social security, Medicare, Pell Grant, all the social services”? You just told them you’re out of money. And you told North Korea that we won’t be able to defend ourselves. It’s obviously intended to shake people up and scare some senators into opposing the bill, to get voters worried so that they turn the pressure up. But it’s a crazy statement to have made.

So yes, I think no one around Obama either understood or was going to explain this to him.

What do we do now? What is the next move for people who are getting screwed by this bill?

What do you do? You better sweep the House, you better take back the Senate, and take back the White House in 2020, and hold your resistance at a very high level. I mean, people have to be prepared to stand up and fight back. There’s three more years before there’s any chance of changing course. If you win the House in 2018, you can at least stop a lot of stuff from happening. That has to happen. That’s the quickest way to stop the pain for the poor and the middle class—because we can expect more of this for three more years if we don’t.

So, that’s number one. To the extent that people are able, in an environment like this, to organize, to protect themselves in the workplace, to form unions—those are safeguards. Communities are doing more. States like New York, California, and Tennessee are moving to make public colleges and universities tuition-free. Fight for $15 has made the greatest inroads in blue states. In places where it’s still possible to make gains in policy—environmental, economic, racial, and social justice policy—those fights will continue. But at the national level it’s going to be very difficult if 2018 comes to pass and the Republicans still have the Senate, the House, and of course the White House.

Many people on the left argue that the Democrats need a more inspiring platform to run on, one that includes big spending policies to fix the economy and repair the social safety net. The Center for American Progress recently floated the idea of a job guarantee, which is a longstanding proposal on the left. What other good ideas should the Democrats be stealing?

Here’s the great thing: they don’t have to steal them, they just have to remember them. The most beloved President of all time, the guy who won four times—FDR—left us with a blueprint for an agenda that the Democrats have ready-made for them, and that is the Second Bill of Rights. This should be considered the unfinished business of the Democratic Party.

People are so damn frustrated. They go year after year, working harder and harder, and never get ahead. There’s so much anxiety. Work has become more precarious, people don’t know their hours ahead of time, bosses schedule changes at the last minute. A third or so of the working population is engaged in some kind of freelance employment. These are not the kinds of jobs that people had forty years ago, when they had a job for life and got regular pay increases and had a pension. People don’t have safety and security.

So what is the Second Bill of Rights? It’s a safety and security contract. It’s a social contract. And it says, as a citizen of the country, you have a right to employment at a decent wage. You have a right to health care. You have a right to a secure retirement. You have a right to an education. There’s also a right to housing on that list.

If you stood as a party for those basic rights, those fundamental rights, you could win. Everything else is up to you. You could still have a capitalist economy, where people still have to compete and work hard if they want more than the basics, so there are still plenty of incentives to be innovative and invest and all that—but the basics are guaranteed. It removes that insecurity, that anxiety that you won’t be able to send your kids to college or aren’t going to have money to survive on for retirement. If you look at surveys, when you ask peope “At what age do you expect to retire?” A share of the population says, “I’m never going to be able to retire, I’m going to work until I die, because I can’t afford it. I don’t have anything set aside. I don’t have a 401k or a pension or whatever. I can’t live on social security, so I’m never going to retire.” I don’t think the Democrats need to steal ideas. I think they need to remember what this party once stood for and champion a bold agenda.

What about journalists and talking heads, what can they do? How are they contributing to misconceptions about federal spending?

Journalists have been very bad. They have just repeated the same talking points that the Republicans got from Peter Peterson. “Fix the Debt” is an absolutely toxic campaign, and it came out of the Peterson Foundation.

What’s the Peterson Foundation?

The Peterson Foundation is Peter Peterson’s nonprofit umbrella organization. He’s a billionaire whose dream in life seems to be the evisceration of what remains of the New Deal or the Great Society. If it had to do with LBJ or FDR, Peterson wants no trace of it. So, Medicare, which came from LBJ—gone. Social security, from FDR—gone. He wants to gut entitlements.

Underneath the Peterson Foundation is “Fix the Debt,” his $60 million campaign to convince people that the deficit is a national crisis as a way to justify austerity and privatization. Joe Scarborough and half the people who sit at the table every morning on MSNBC with Scarborough, either are or have been affiliated with Fix the Debt. Senators from the state of Virginia, Tim Kaine and Mark Warner, both Democrats—Fix the Debt gave them awards. So anyone who comes under the spell of this Pete Peterson “Fix the Debt” stuff gets their talking points from him. It’s Republicans and Democrats. Angus King, Independent. Paul Ryan is dogmatic: “How can we do this to our children and grandchildren?” And then you have Democrats repeating exactly the same arguments.

So Peterson is a very bad guy. Bernie always talks about Pete Peterson. And I mean, he is my nemesis. I wake up every single day, and the motivation for crawling out of bed is to do battle with this faction. Because it’s powerful! And it’s incredibly destructive. It’s mind-warping and it’s brain-washing. Fix the Debt goes out and gets these people to be talking heads—they recruit them, pay them, train them, send them out—and then suddenly you have an army of pundits and people writing in the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times pushing this hysteria. So that’s all anybody’s ever heard: that deficits are bad, the debt is bad, and the US faces a long-term debt crisis. Even a guy like Paul Krugman, the most he can do is muster, “Well, it’s only a long-run problem, not a short-run problem,” which is the same as saying “we have a deficit crisis, it’s just not here yet.”

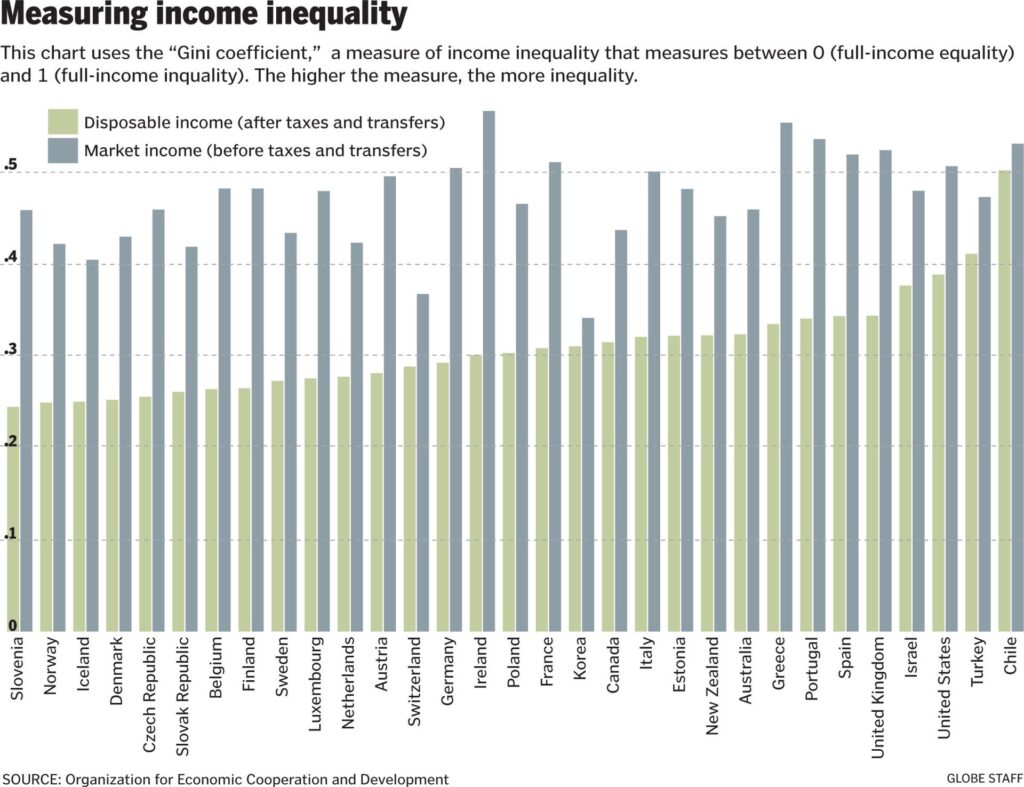

Very few people are trying to explain anything to any American other than that. They argue about when it’s coming—“How fast is the sky falling?”—but not enough are saying that the national debt is not a national crisis. The fact that 21 percent of all children in the United States live in poverty—that’s a crisis. The fact that our infrastructure is graded at a D+, that’s a crisis. The fact that income inequality is at 1920s levels is a crisis. The fact that wages haven’t increased in real terms, that’s a crisis. Those are real crises. The national debt is not a crisis.