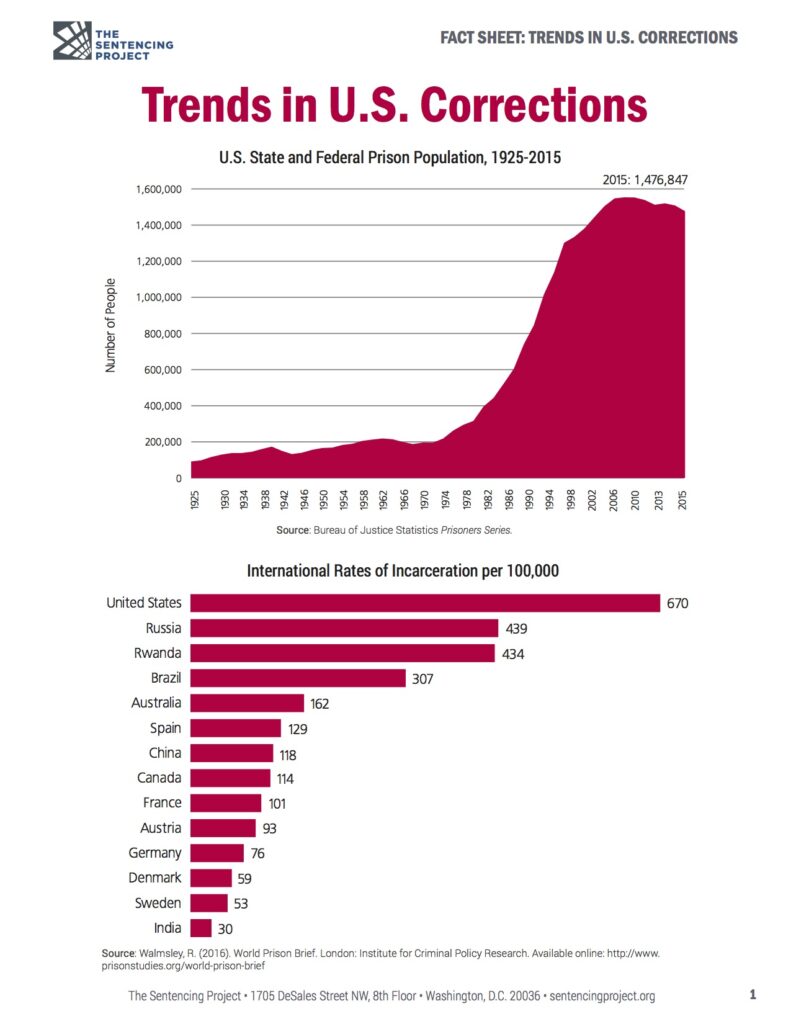

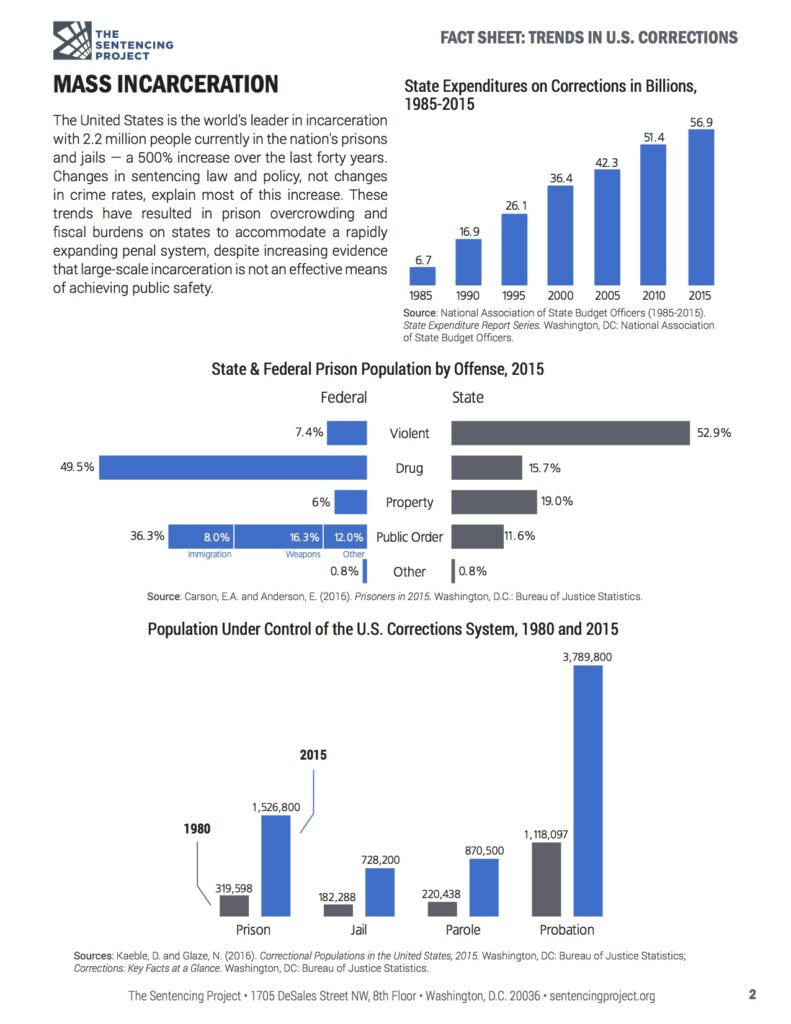

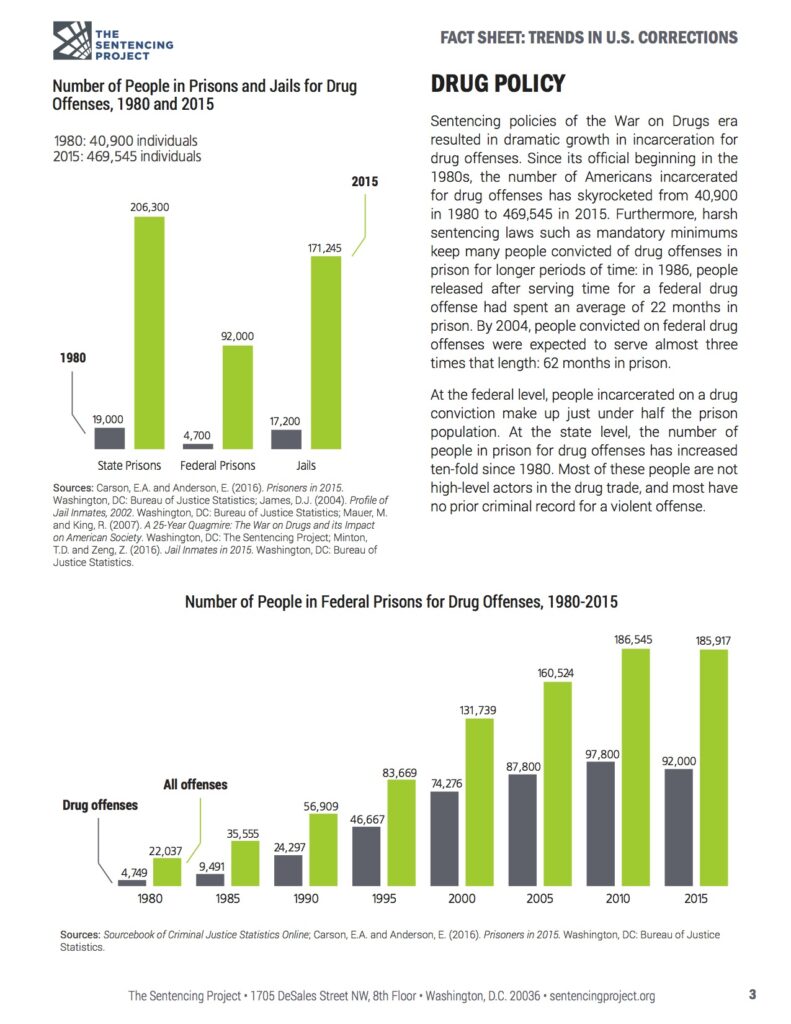

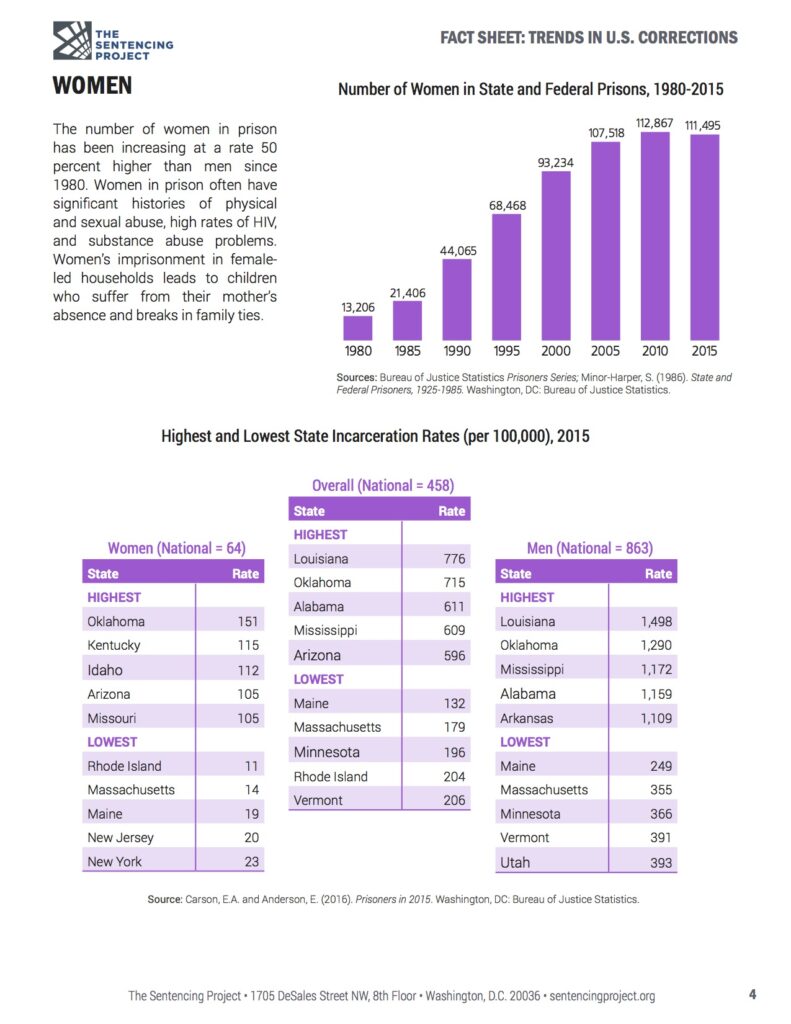

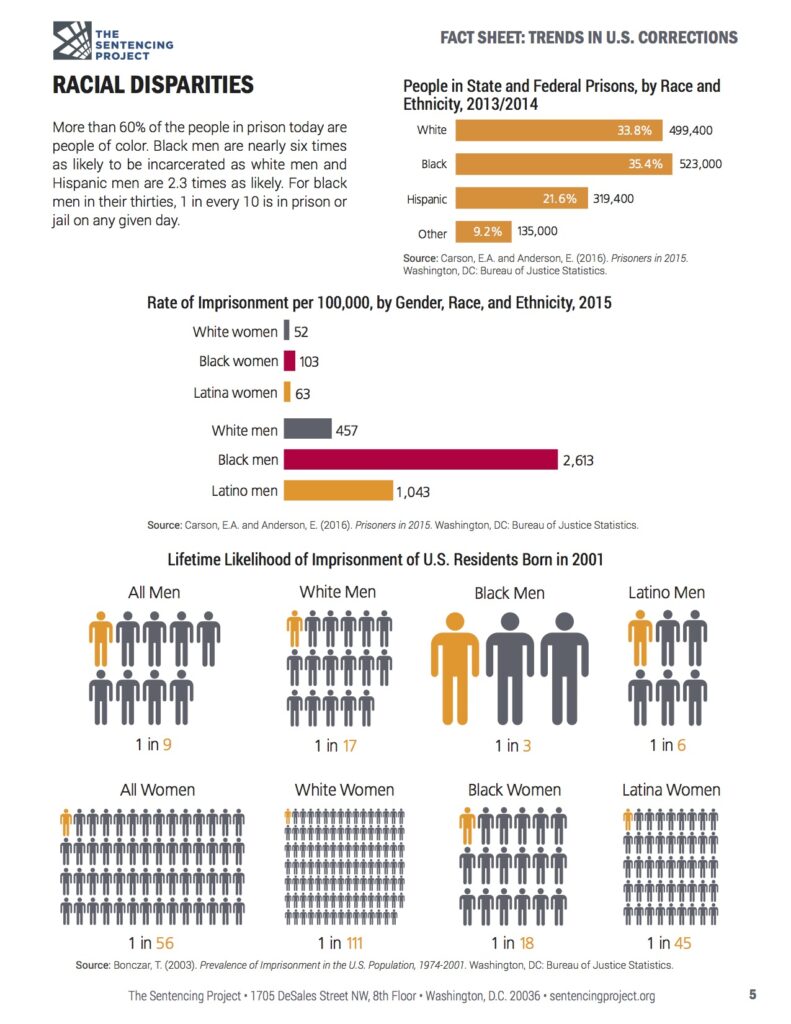

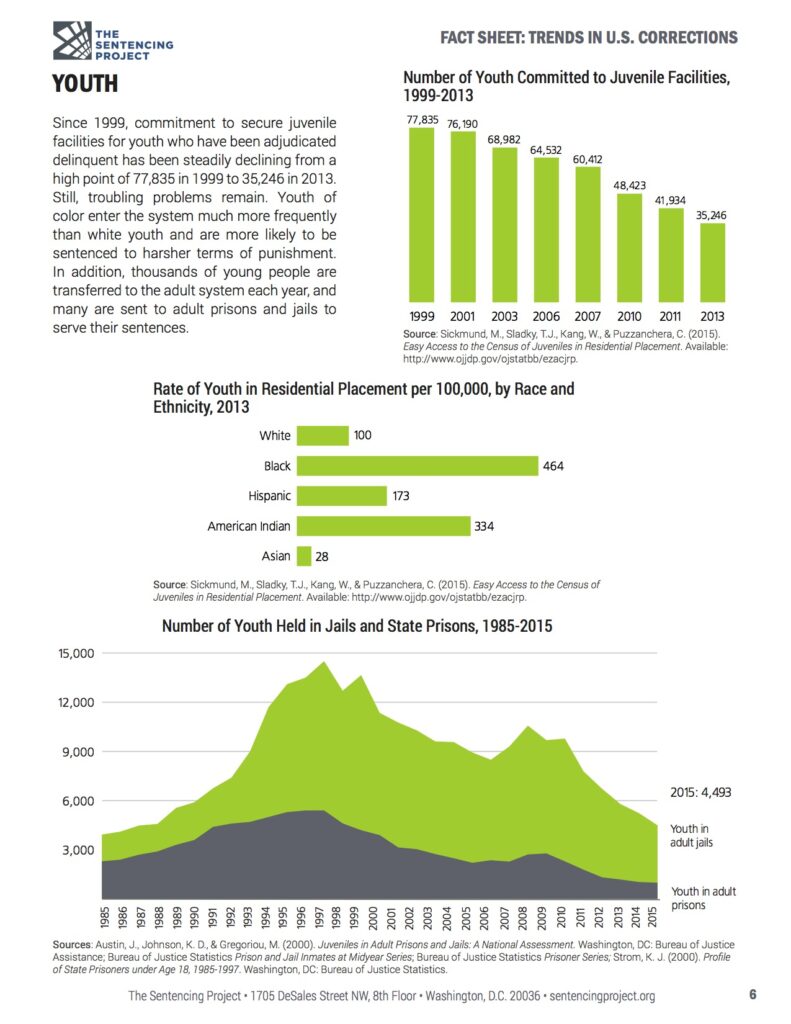

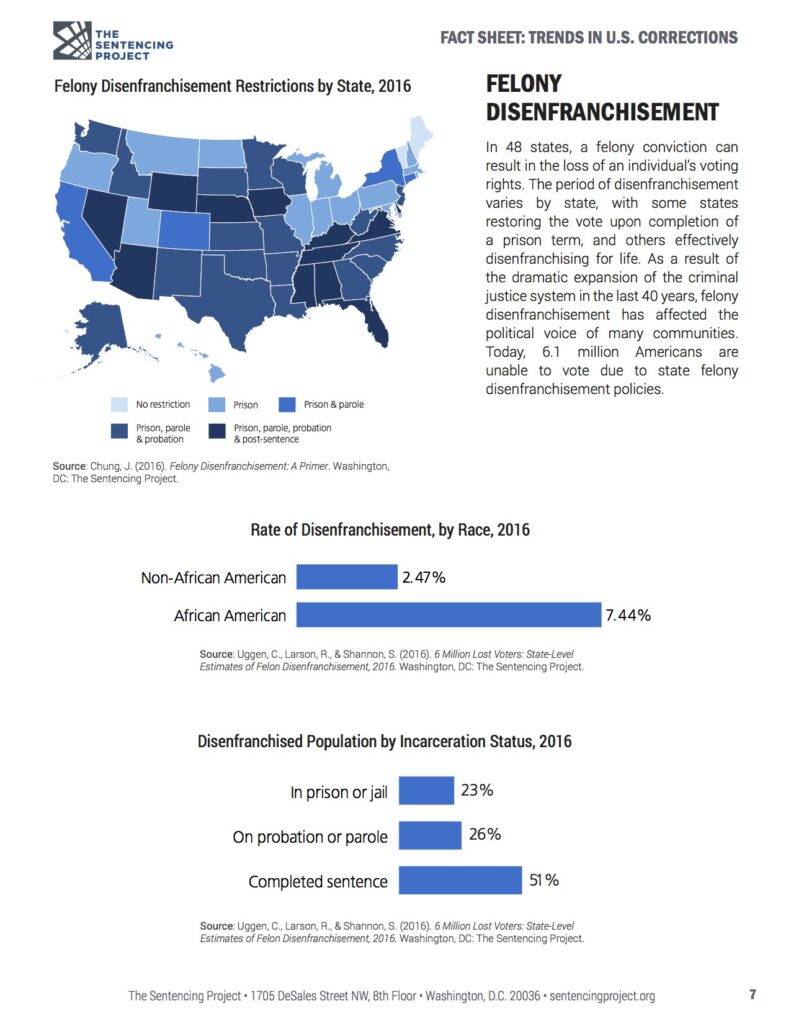

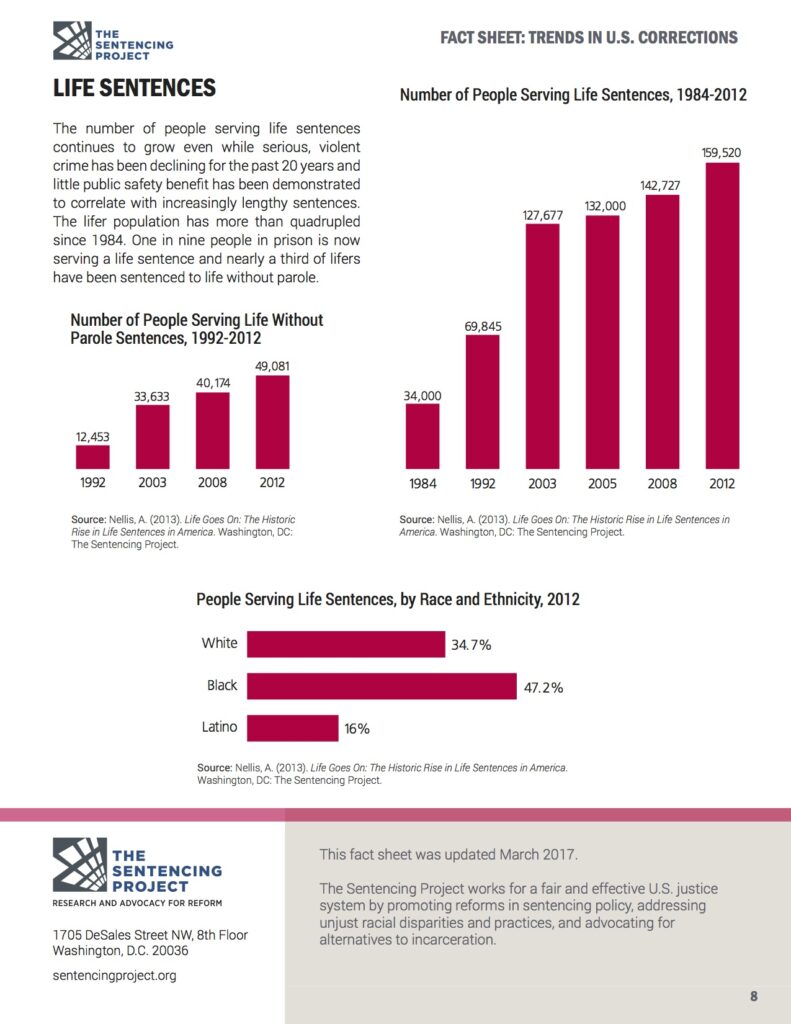

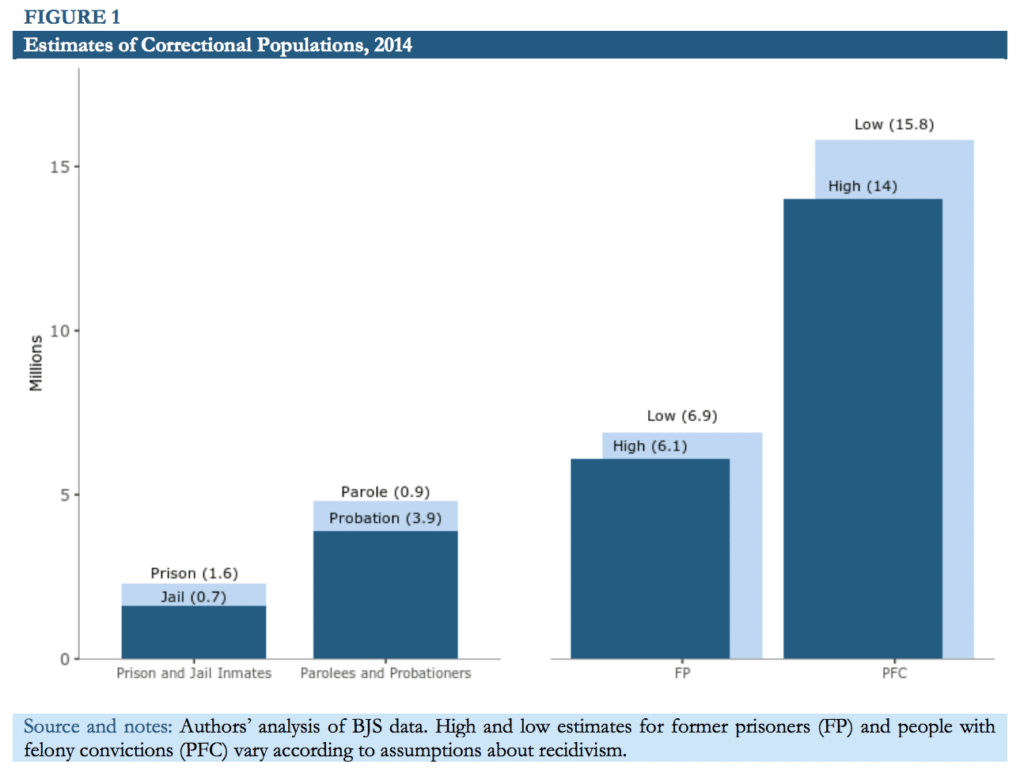

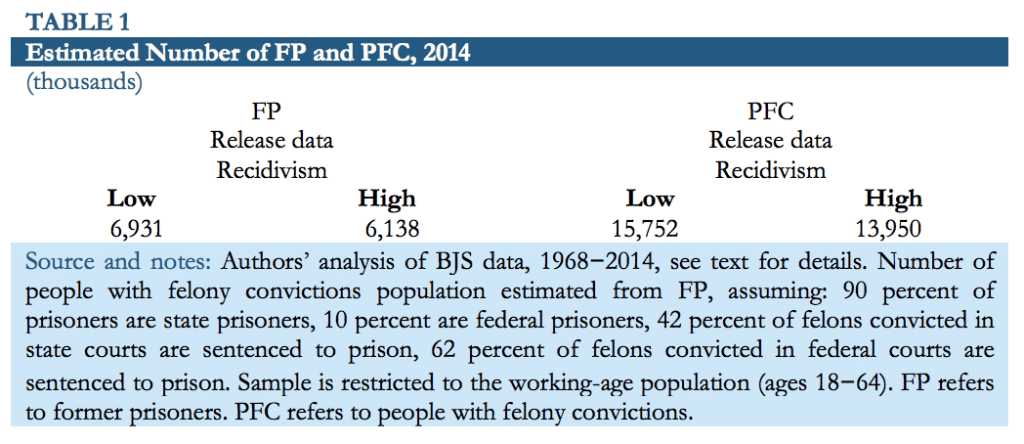

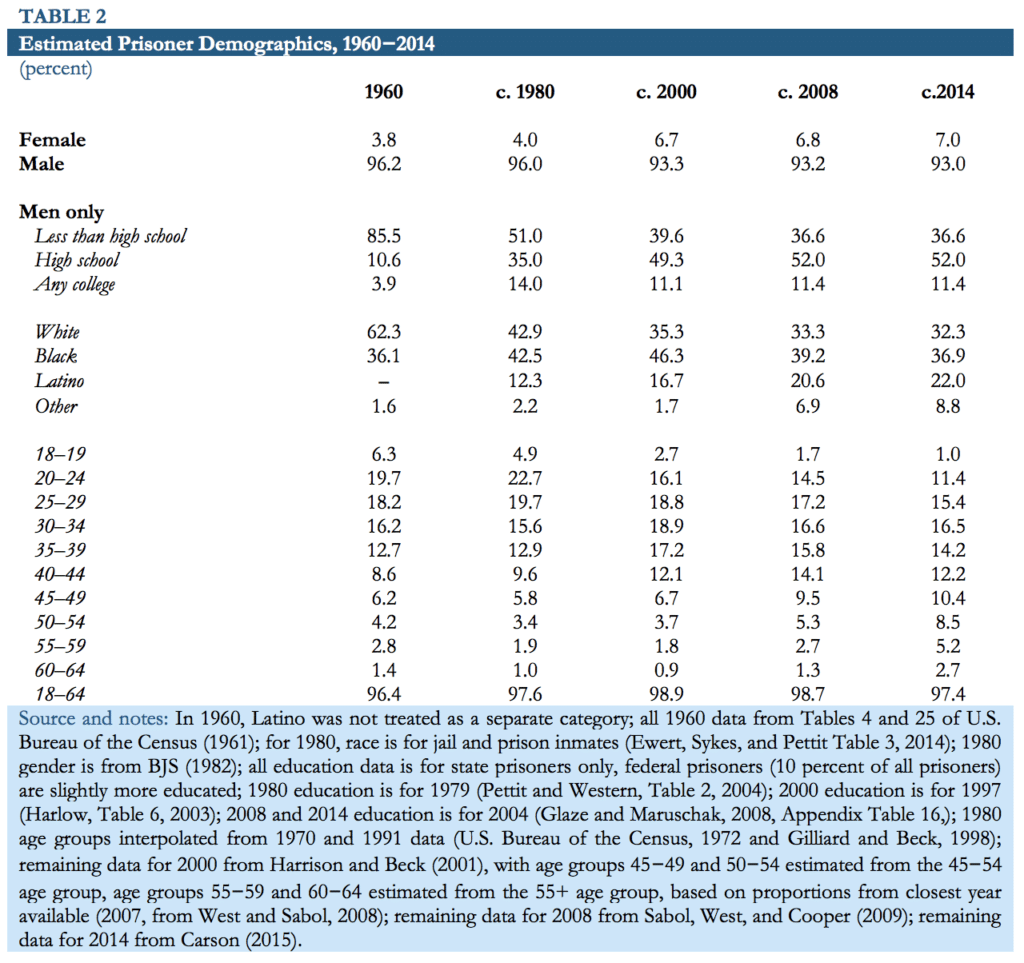

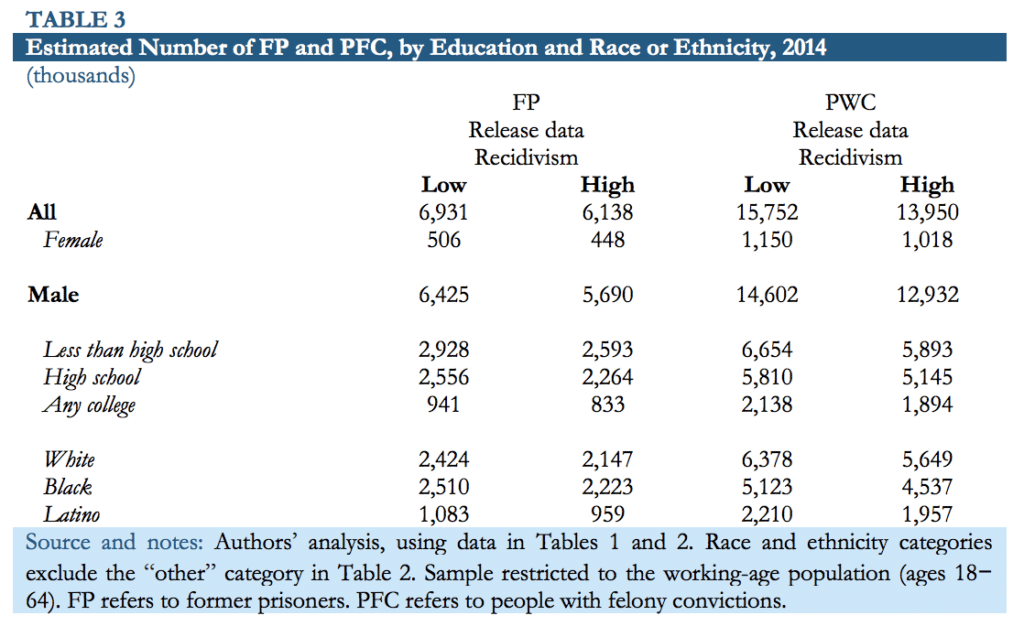

From The Sentencing Project, we present a fact sheet of Trends in U.S. Corrections, including prison populations, state and federal expenditures, the number of people in prisons and jail for various offenses, facts on women and race, as well as much more.