The United States is the wealthiest nation in the history of the world and we have been a leader in so many ways across different generations. However, when it comes to climate science and renewable energy we are falling behind other countries who have taken the leadership and initiative to move towards 100% renewable energy.

Achieving 100% renewable energy is possible and plausible for the United States of America.

Many other developed nations have almost completely incorporated renewable energy into their economies and have been able to power their entire countries for substantial amounts of time solely on these methods. Others are moving in that direction and achieving small steps – a day, a month, an industry, solely relying on renewable energy.

Here are some renewable energy leaders leaders around the world:

Costa Rica

Costa Rica has been a world leader in renewable energy for years. In 2015, Costa Rica ran on 100% renewable energy for 285 days, and on 100% renewable energy for 250 days in 2016. According to The Costa Rica News, in 2017, “Costa Rica achieved the admirable 300-day in a row mark in which its electric system operated with exclusively renewable sources, mainly [hydroelectric], besides the production of renewable energy covered 99.62% of the electricity needs of the country. A mark that also exceeds the records of 2015 and 2016.” Costa Rica does this through relying heavily on hydroelectric power, wind energy, geothermal energy, and small amounts of solar energy and biomass. This commitment to renewable energy has, according to the Costa Rica News “turned Costa Rica into the largest producer of clean energy from all of Central America and the Caribbean.”

Iceland

Almost 100% of all energy consumed on Iceland is renewable energy. The UN describes that in addition, “9 out of every 10 houses are heated directly with geothermal energy.” Iceland meets it energy needs largely through hydroelectric and geothermal sources. The UN acknowledges that the only exception to Iceland’s pervasive use of renewable energy is its reliance on fossil fuels for transport. The UN describes that Iceland’s move from fossil fuels to renewable energy was not inspired by climate change, instead, “The drive behind this transition was simple—Iceland could not sustain oil price fluctuations occurring due to a number of crises affecting world energy markets. …[and] for its isolated location on the edge of the Arctic Circle.” To rectify this issue, Iceland hired local businesses and entrepreneurs to shift energy reliance from foreign providers to internal sources. The Icelandic government also creates policies to encourage this shift: “To further incentivize geothermal energy utilization, the Government of Iceland established a geothermal drilling mitigation fund in the late 1960s. The fund loaned money for geothermal research and test drilling, while providing cost recovery for failed projects. The established legal framework also made it attractive for households to connect to the new geothermal district-heating network rather than to continue using fossil fuels.” The UN describes that these projects also diversified the economy, created jobs, and established a nationwide power grid.

Norway

“In Norway, 98 percent of the electricity production come from renewable energy sources,” according to the Norwegian government. The vast majority of Norway’s renewable energy comes from hydropower, an industry that has been growing in Norway since the 1800s. However, wind and thermal energy also contribute. Unlike many other countries, the Norwegian government explains that 90 % Norwegian energy production is owned by the state, counties, and municipalities “to secure a role for the Norwegian state in the ongoing electrification of the country, and ensure that the hydropower resources would benefit the nation as a whole.”

Portugal

In March of 2018, Portugal produced 103.6% of the energy required to meet the country’s electrical demand. According to NPR, “Fifty-five percent of that energy was produced through hydro power, while 42 percent came from wind.” Based on this success, Portugal expects that by the year 2040 that “the production of renewable electricity will be able to guarantee, in a cost-effective way, the total annual electricity consumption of Mainland Portugal.”

Germany

In January of 2018, Germany briefly covered 100% of its energy demand through renewable energy. In addition, according to Clean Energy Wire, last year “In the whole of last year, the world’s fourth largest economy produced a record 36.1 percent of its total power needs with renewable sources.” Due to the growing presence of renewable energy in Germany, there are now days when Germany generates half of its power from the sun.

While powering a country with 90% to 100% renewable energy might seem a daunting task for larger economies, many other foreign governments have invested in making certain aspects of their economy run entirely on renewable energy, or have focused on specific areas of the country, setting reasonable (and achievable) goals that will serve as test cases for later expansion of renewable energy. Some of these countries include:

China

In July of 2017 the Chinese announced that Qinghai Province—a territory the size of Texas—had gone a week relying on 100% renewable energy including solar, wind, and hydropower. During that week, Business Insider reports that “the Qinghai province generated 1.1 billion kilowatt hours of energy for over 5.6 million residents. That’s equal to burning 535,000 tons of coal.” This week period was a test by the Chinese government to test the viability of relying on renewables long-term. Ultimately, “China hopes to produce 20% of its electricity from clean sources by 2030.”

About the same time the Chinese released aerial photos of their newest giant solar farm—which seen from above depicts a cheerful black-and-white panda. Business Insider reports that, “it will be able to produce 3.2 billion kilowatt-hours of solar energy in 25 years… reducing carbon emissions by 2.74 million tons.”

England

On April 21st2017, Great Britain managed to meet its power demands without burning a lump of coal for the first time since the launch of the Industrial Revolution. This is one small step towards a transition away from fossil fuels to meet Great Britain’s climate change commitments. The Guardian reports that, Hannah Martin, the head of energy at Greenpeace UK, described this milestone as part of a much larger movement: “The first day without coal in Britain since the Industrial Revolution marks a watershed in the energy transition. A decade ago, a day without coal would have been unimaginable, and in 10 years’ time our energy system will have radically transformed again.”

Holland

In 2015 Holland set a goal to power all Dutch electric trains with wind energy by 2018. By January of 2017, that goal had been met. According to The Guardian, Holland met their goal a year ahead of schedule due to, “an increase in the number of wind farms across the country and off the coast of the Netherlands.”

Chile

Solar production has grown six-fold since 2014 in Chile. In fact, the New York Times reported that “Chilean officials have an even more ambitious projection, saying the country is on track to rely on clean sources for 90 percent of its electricity needs by 2050, up from the current 45 percent.” The initial movement to renewable energy sources was largely due to the high cost and uncertainty of energy supply when that energy was provided by outside sources. In addition, due to severe weather events that have made hydropower plants less reliable in Chile, the government has turned to more varied sources including wind, solar, and geothermal energy sources.

India

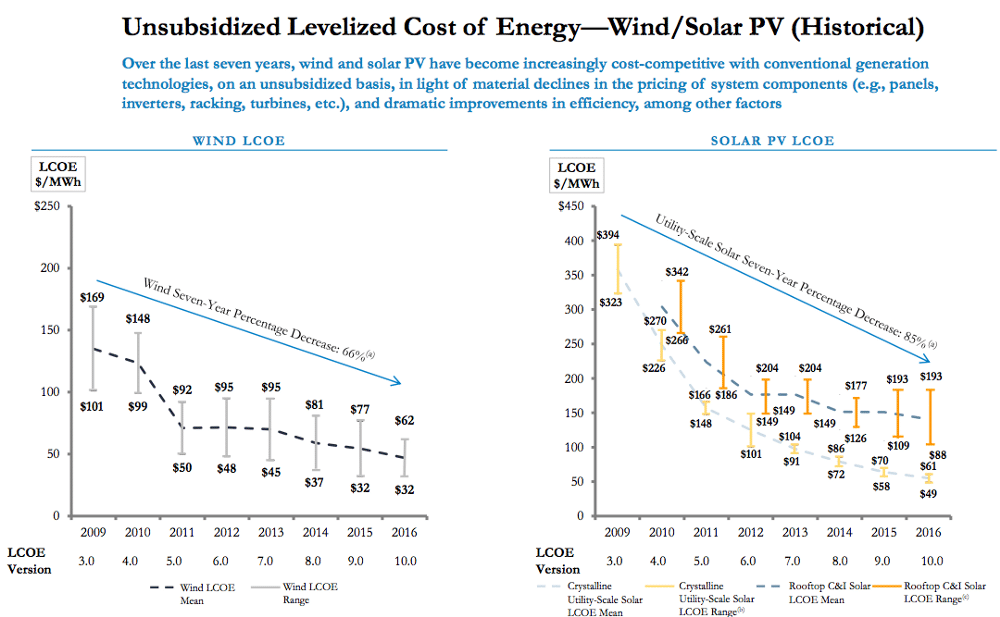

The largest coal mining company in the world (which produces 82% of India’s coal), announced the closure of dozens of coal mines and the cancellation of plans for dozens of new coal-fired generation stations because the cost of solar power was significantly undercutting fossil fuel. The Independent describes that “India’s solar sector has received heavy international investment, and the plummeting price of solar electricity has increased pressure on fossil fuel companies in the country.” The Independent also reports that “The government has announced it will not build any more coal plants after 2022 and predicts renewables will generate 57 per cent of its power by 2027.”

The United States

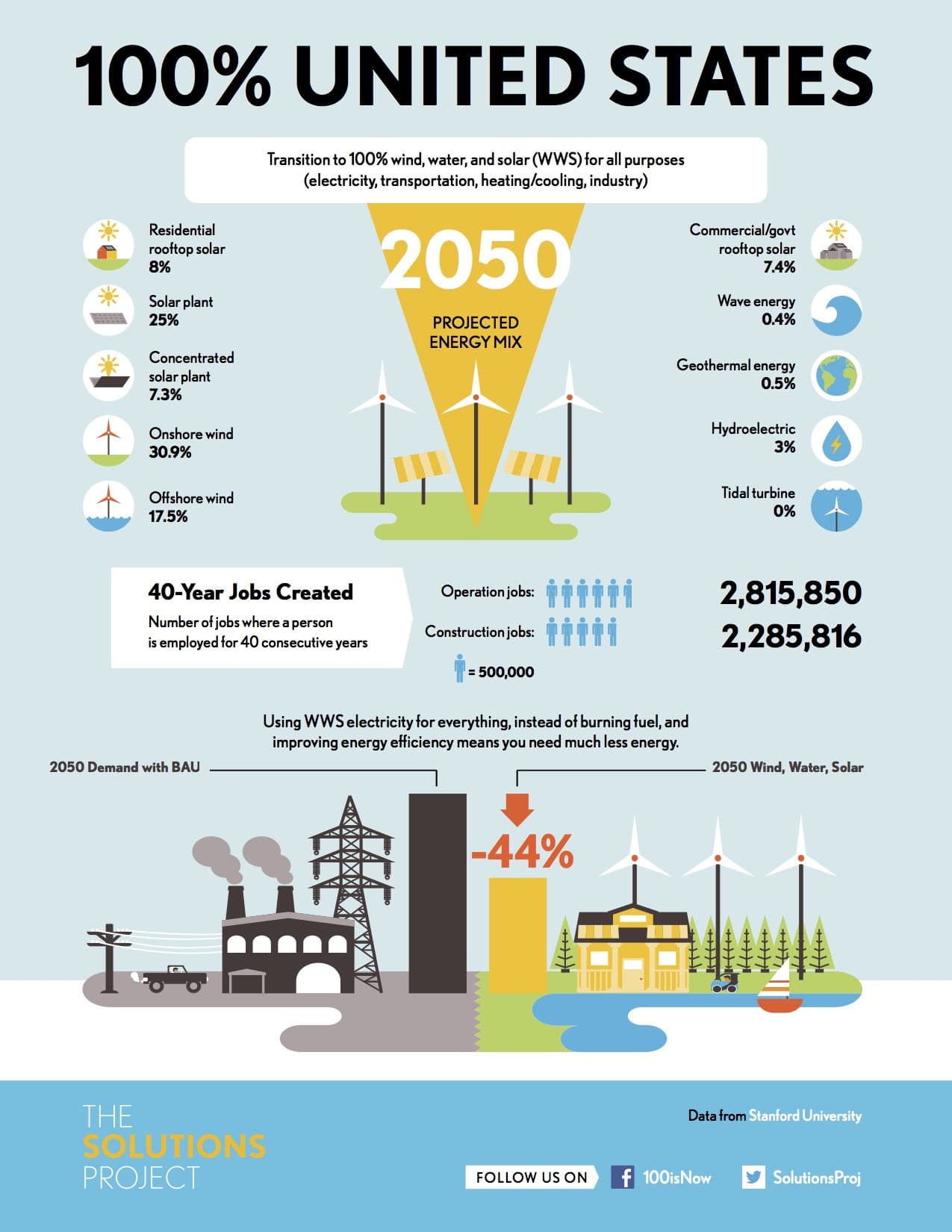

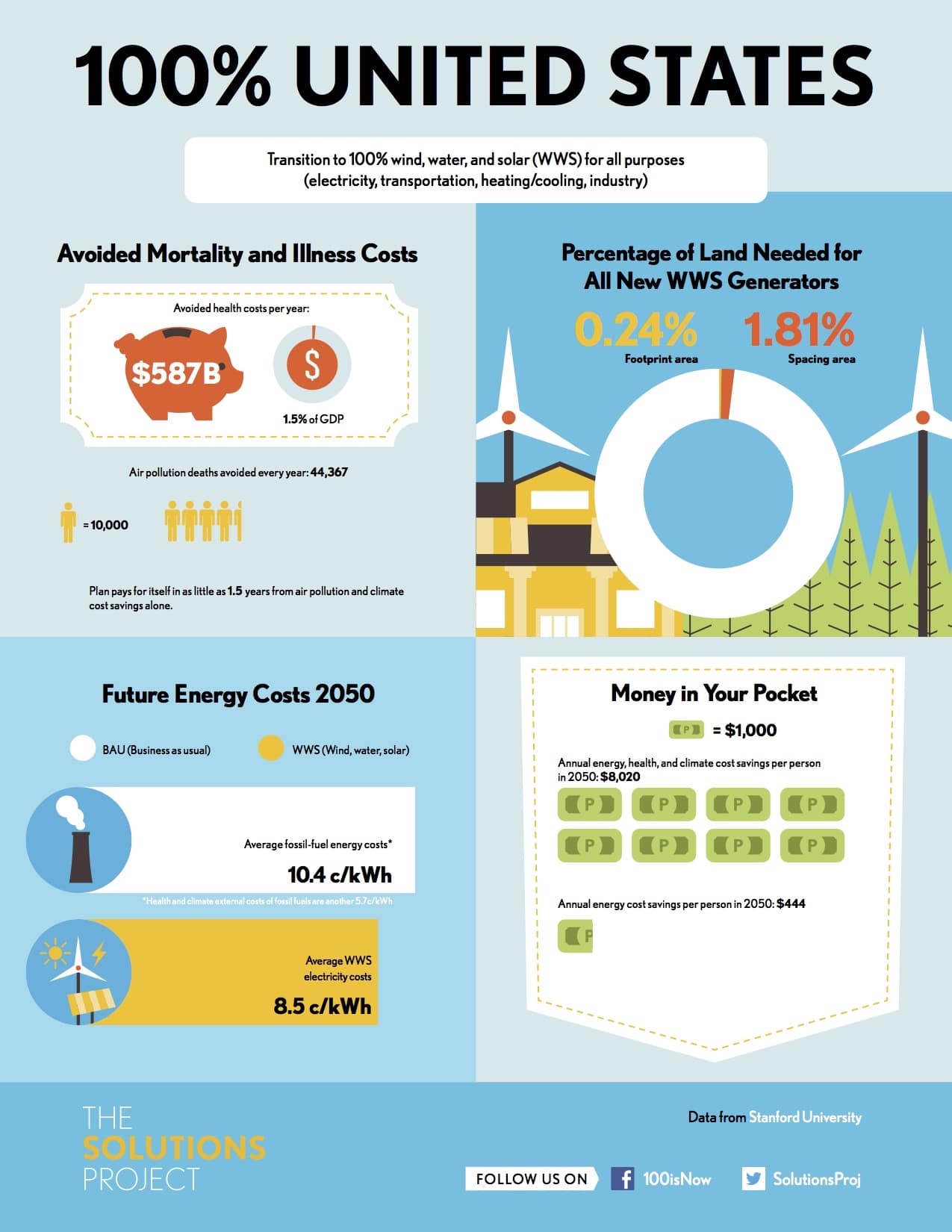

Governmental steps taken to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and to move towards a clean and green future are not solely happening outside of the United States. Fortune reports that “Eighteen percent of all electricity in the United States was produced by renewable sources in 2017, including solar, wind, and hydroelectric dams. That’s up from 15% in 2016.” Since 2008, renewable share of energy consumption has doubled. This is largely due to market forces that are responding to the dropping price of solar and wind energy. Fortune also points out that “the solar and wind industries are creating jobs faster than the rest of the economy.”

Many cities and states are, in fact, far outpacing the rest of the United States and have taken even greater steps towards 100% renewable energy. Below are two examples:

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

In June of 2017, President Trump announced that he would pull the United States out of the Paris Climate Agreement citing that he was elected by the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris. In response, the Mayor of Pittsburgh, Bill Peduto responded in a press release that “Pittsburgh will not only heed the guidelines of the Paris Agreement — we will work to move towards 100 percent clean and renewable energy for our future, our economy, and our people.”

Since June of last year, Mayor Peduto have taken steps to make that goal a reality. On April 5th of 2018, 180 U.S. Mayors including Mayor Peduto signed a letter resolving to make solar power a key element in their renewable energy plans. A press release quoted Mayor Peduto: “Solar power is a key component of advancing Pittsburgh’s clean energy transition. We have numerous assets that can provide as the launching point for solar generation in Pittsburgh and southwestern Pennsylvania, from parking lots to rooftops. Increasing the amount of locally generated solar power helps reduce carbon pollution, clean our air and provide a resilient, sustainable and cost-effective electricity.”

The next month, Pittsburg released its Climate Action Plan that establishes a goal for 100% renewable energy, and 100% fossil fuel free by 2030 as well as complete divestment from the fossil fuel industry.

Hawaii

Cities are not the only entities in the United States that are working towards 100% renewable energy. Hawaii is an example of an entire state that is working toward that goal.

In 2008 Hawaii and the Department of Energy signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) “to collaborate on the reduction of Hawaii’s heavy dependence on imported fossil fuels.” The Hawaii Clean Energy Initiative was begun by that agreement. In 2014, the initial goals were renewed and upgraded to include:

- Achieving the nation’s first-ever 100 percent renewable portfolio standards (RPS) by the year 2045.

- Reducing electricity consumption by 4,300 gigawatt-hours by 2030, enough electricity to power every home on Oahu, Maui, Molokai, Lanai and Hawaii Island for more than two years.

- Reducing petroleum use in Hawaii’s transportation sector which accounts for two-thirds of the state’s overall energy usage.

In July of 2017, the Hawaii Public Utilities Commission approved an official plan put forward by Hawaiian Electric Companies that laid out exactly how Hawaii would achieve 100% renewable energy by 2040 (five years ahead of the goal.)

Hawaii serves as a reminder that states too can make significant headway towards the goal of 100% renewable energy. Progress is possible and is happening, if slowly.

If you would like to know more about how your state can move towards 100% renewables based on scientific studies that have analyzed the renewable energy potential in each area, visit The Solutions Project website.

A list of cities, counties, and states committed to, or that have achieved 100% renewable energy can also be found here.