The immediate question is whether Silicon Valley Bank’s failure is the start of a more general bank crisis. The rise of market interest rates caused by the Fed and European Central Bank’s tightening has impaired other banks as well. Now that a banking crisis has occurred, panics by depositors are more likely.

The banking crisis that hit Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) two weeks ago has spread. We recall with a shudder two recent financial contagions: the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, which led to a deep Asian recession, and the 2008 Great Recession, which led to a global downturn.

The new banking crisis hits a world economy already disrupted by pandemic, war, sanctions, geopolitical tensions and climate shocks.

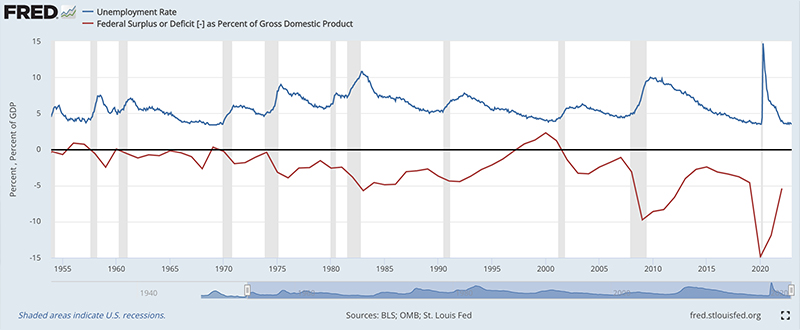

At the root of the current banking crisis is the tightening of monetary conditions by the Federal Reserve (the Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB) after years of expansionary monetary policy. In recent years, both the Fed and ECB held interest rates near zero and flooded the economy with liquidity, especially in response to the pandemic.

Easy money resulted in inflation in 2022, and both central banks are now tightening monetary policy and raising interest rates to staunch inflation.

Banks like SVB take in short-term deposits and use the deposits to make long-term investments.

The banks pay interest on the deposits and aim for higher returns on the long-term investments. When the central banks raise short-term interest rates, rates paid on deposits may exceed the earnings on long-term investments. In that case, the banks’ earnings and capital fall. Banks may need to raise more capital to stay safe and in operation. In extreme cases, some banks may fail.

Even a solvent bank may fail if depositors panic and suddenly try to withdraw their deposits, an event known as a bank run. Each depositor dashes to withdraw deposits ahead of the other depositors. Since the bank’s assets are tied up in long-term investments, the bank lacks the liquidity to provide ready cash to the panicked depositors. SVP succumbed to such a bank run and was quickly taken over by the US government.

Bank runs are a standard risk but can be avoided in three ways. First, banks should keep enough capital to absorb losses. Second, in the event of a bank run, central banks should provide banks with emergency liquidity, thereby ending the panic. Third, government deposit insurance should calm depositors.

All three mechanisms may have failed in the case of SVB. First, SVB apparently allowed its balance sheet to become seriously impaired and regulators did not react in time. Second, for unclear reasons, US regulators closed SVB rather than provide emergency central bank liquidity. Third, US deposit insurance guaranteed deposits only up to $250,000, and so did not stop a run by large depositors. After the run, US regulators announced they would guarantee all deposits.

The immediate question is whether SVB’s failure is the start of a more general bank crisis. The rise of market interest rates caused by Fed and ECB tightening has impaired other banks as well. Now that a banking crisis has occurred, panics by depositors are more likely.

Future bank runs can be avoided if the world’s central banks provide ample liquidity to banks facing runs. The Swiss Central Bank provided a loan to Credit Suisse for exactly this reason. The Federal Reserve has provided $152-billion in new lending to US banks in recent days.

Emergency lending, however, partly offsets the central banks’ efforts to control inflation. Central banks are in a quandary. By pushing up interest rates, they make bank runs more likely. If they keep interest rates too low, however, inflationary pressures are likely to persist.

The central banks will try to have it both ways: higher interest rates plus emergency liquidity, if needed. This is the right approach, but comes with costs. The US and European economies were already experiencing stagflation: high inflation and slowing growth. The banking crisis will worsen the stagflation and possibly tip the US and Europe into recession.

Some of the stagflation was the consequence of Covid-19, which induced the central banks to pump in massive liquidity in 2020, causing inflation in 2022. Some of the stagflation is the result of shocks caused by long-term climate change. Climate shocks could become worse this year if a new El Niño develops in the Pacific, as scientists say is increasingly likely.

Yet stagflation has also been intensified by economic disruptions caused by the Ukraine War, US and EU sanctions against Russia, and rising tensions between the US and China. These geopolitical factors have disrupted the world economy by hitting supply chains, pushing up costs and prices while hindering output.

We should regard diplomacy as a key macroeconomic tool. If diplomacy is used to end the Ukraine war, phase out the costly sanctions on Russia, and reduce tensions between the US and China, not only will the world be much safer, but stagflation will also be eased. Peace and cooperation are the best remedies to rising economic risks.