We watch in horror as the damages from climate change continue to mount.

Last year, Hurricane Harvey dropped more rain on Houston than any storm has ever dropped on any American city, ever. Hurricane Maria set back development in Puerto Rico 25 years, according to early estimates. And the tab keeps mounting: in 2017 alone, the economic cost of hurricanes and wildfires was greater than the cost of paying tuition for every American in a public college or university. We can’t have a working nation or a world if we don’t stop the climate from careening out of control. That’s been clear for decades now, but what’s been less clear is precisely what we should do about it.

Happily, that’s no longer the case. We now know exactly what to do, and we’re increasingly certain it can be done. We have to switch off of coal, oil, and gas, and on to 100% wind, water, and sun energy sources. And though this drive for a conversion to clean energy started in northern Europe and northern California, it’s a call that’s gaining traction outside the obvious green enclaves. More and more major US cities have taken the pledge to go 100% renewable by the year 2050, while others have taken action to sever their ties with the fossil fuel industry, signifying a global shift in how we’re thinking about our energy system.

What Medicare for All is to the health care debate, or Fight for $15 is to the battle about inequality, 100% Renewable is to the struggle for the planet’s future. It’s how progressives will think about energy going forward.

Former President Barack Obama drove environmentalists crazy with his “all of the above” energy policy, which treated sun and wind as two items on a long menu that also included coal, gas and oil. That’s simply not good enough. No more half-measures.

Scientists now tell us that at current rates, within a decade we’ll likely have put enough carbon in the atmosphere to warm the earth past the Paris climate targets. And in any event there’s no need any longer to go slow: engineers have in the last few years brought the price of renewables so low that it would make sense to switch over even if fossil fuel wasn’t wrecking the earth. In fact, that’s why the appeal of 100% renewables goes well beyond the left: if you pay a power bill, clean energy is increasingly the common-sense path forward. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to happen automatically: the fossil fuel industry recognizes its peril, and is rallying all the political power its cash reserves can buy to prevent the idea getting traction. It’s going to be a hell of a fight.

“..if you pay a power bill [100% renewable] is increasingly the common-sense path forward.”

To understand why it took a while to get here, consider the solar panel. We’ve actually had this clever device for quite a while: Bell Labs produced the first recognizable models in 1954. They were only about four percent efficient, and they were incredibly expensive to produce, which meant that they didn’t find many uses on planet Earth. In space, however, they were essential: Buzz Aldrin deployed a solar panel on the moon not long after Apollo 11 touched down.

Improvements in efficiency and drops in price came slowly for the next few decades (Ronald Reagan, you may recall, took down the solar panels Jimmy Carter had installed atop the White House). But in 1998, with climate fears on the rise, Germany’s Green Party found itself holding the political balance of power after a close election. In return for its support, the Social Democratic government began moving quickly toward renewable energy. German demand for solar panels and wind turbines coincided with rapidly growing Chinese industrial capacity in the early years of the new millennia, as factories across the People’s Republic learned to make the panels ever more cheaply.

There are now days when Germany generates half of its power from the sun—and, more to the point, the price of a panel began to truly plummet years ago, a freefall that continues to this day. By 2017, solar or wind power had won most competitive bids for electric supply, and India announced the closure of dozens of coal mines and the cancellation of plans for dozens of new coal-fired generation stations because the cost of solar power was badly undercutting fossil fuel. Even in places like Abu Dhabi, the comparative advantage of free power from the sun is impossible to resist, and massive arrays are going up amidst the oil fields.

“What Medicare for All is to the health care debate, or Fight for $15 is to the battle about inequality, 100% Renewable is to the struggle for the planet’s future. “

One person who noticed the falling prices and improving technology early on was Mark Jacobson, the director of Stanford University’s Atmosphere and Energy Program. In 2009 his team published a series of plans showing how the United States could generate all its energy from the sun, the wind, and the falling water that produces hydropower. Two years later, along with actor Mark Ruffalo and other co-conspirators, Marc co-founded The Solutions Project to take the idea out of academic journals and into the real world. The group has since published similarly detailed plans for most of the planet’s countries. (If you want to know how many acres of south-facing roof you can find in Alabama, or how much wind blows across Zimbabwe, these are the folks to ask).

With each passing quarter the price of solar and wind power has fallen farther, moving the 100 percent target from aspirational goal to the obvious solution. I spent the spring of 2017 in some of the poorest parts of Africa where people—for the daily price of enough kerosene to fill a single lamp—were now installing solar panels and powering up TVs, radios, and LED bulbs. If you can do it in Germany and you can do it in Ghana, you can probably do it in Grand Rapids and Gainesville.

That’s especially true since renewable energy is lights-on popular across the American political spectrum. The polling data is almost unbelievable: in a country with a yawning partisan gulf on virtually every issue, one poll after another shows that massive majorities of Democrats, Republicans and independents favor government action to develop renewable energy.

“The fossil fuel industry is well aware that they’re not the future, yet they’re determined to keep us stuck in the past as long as possible.”

Even 72% of Republican voters want to “accelerate the development of clean energy” in the United States. That helps explain why, say, the Sierra Club is finding dramatic success with its Ready for 100 campaign. Sure, Berkeley was quick to sign on, and Madison, Wisconsin. But by the early summer of 2017 the U.S. Conference of Mayors had endorsed the drive, and leaders were popping up in unexpected places.

Columbia South Carolina mayor Steve Benjamin even said, “It’s not an option. It’s an imperative.” Environmental groups from Climate Mobilization to Greenpeace to Food and Water Watch are backing the 100% target, differing mainly on how quickly we must achieve the transition, with answers ranging from 2028 to 2050. (The right answer, given the state of the planet, is 25 years ago. The second best response: as fast as is humanly possible.)

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders joined with Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley in the spring of 2017 to propose the first federal 100 percent bill. It won’t pass Congress any time soon, but Congress is not the only legislative body that matters in America—you could make an argument that in the Trump era capitals like Sacramento are just as important.

In a conscious bid to recreate the spirit of the Paris climate talks, California governor Jerry Brown summoned the world’s “sub-national” leaders—governors, mayors, regional administrators—to a giant San Francisco conference in September of 2018:

“Look, it’s up to you, and it’s up to me and tens of millions of other people to get it together to roll back the forces of carbonization and join together to combat the existential threat of climate change,” said Brown, as he invited the world to his gathering. If activists have their way over the next few months, many of those cities and states will arrive in the Bay bearing pledges to take their places totally renewable.

That’s not to say that this fight is going to be easy. The fossil fuel industry is well aware that they’re not the future, yet they’re determined to keep us stuck in the past as long as possible. Every year they can drag out the transition means billions of dollars in revenue.

The arguments against renewables has always been: the sun goes down, the wind ceases to blow. Indeed, one group of academics challenged Jacobson’s calculations last spring partly on these grounds. But technology marches on: Elon Musk’s batteries work in Tesla cars, but scaled up they also make it possible, and economic, for utilities to store the afternoon’s sun for the evening’s electric demand. As one California utility executive said at an industry meeting in May 2017, “The technology has been resolved. How fast do you want to get to 100 percent? That can be done today.”

The trouble, however, is that most utility executives think in very different ways. The growth in new rooftop solar installations has come to what the New York Times called “a shuddering halt,” largely because of “a concerted and well-funded lobbying campaign by traditional utilities, which have been working in state capitals across the country to reverse incentives for homeowners.” Instead of cutting residents a break for helping solve the climate crisis, the utilities—led by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and the Edison Electric Institute (whose lobbying efforts ratepayers actually underwrite)—are eager to end “net-metering” laws that let customers sell excess power they generate back to the grid. That’s pretty much the law that Germany used to make itself a renewable energy powerhouse—and in the process cause huge losses for its utilities.

Rather than trying to adapt to renewable energy, says industry observer Nancy LaPlaca, “utilities have a great monopoly going and they want to keep it.” They use their political clout to make sure that state regulators roll over. Sometimes the results are truly ludicrous—Arizona, for instance, whose capital lies in the “Valley of the Sun” and whose sports fans root for the Suns and the Sun Devils, produces only about 4% of its power from solar energy. Its biggest utility has showered state regulators with dark money to keep it that way—in fact, in the spring of 2017 a former utility commissioner and his wife were indicted by the feds, along with an industry lobbyist, for their role in anti-solar shenanigans.

And it’s not just right-wing Republicans who want to keep business as usual chugging along. Democrats have often found themselves supporting new fossil fuel plans because they are beholden to the building trades unions for campaign support. That was the case last fall when the AFL-CIO, reflecting those building trades members, released a statement supporting the Dakota Access pipeline days after the security companies hired by the oil industry had sicced German Shepherds on indigenous protesters:

“The AFL-CIO supports pipeline construction as part of a comprehensive energy policy,” labor chief Richard Trumka said in a statement. “Pipeline construction and maintenance provides quality jobs.” And of course Donald Trump approved the project early in his presidency, shortly after a cheerful meeting with the heads of the building trades unions. The first oil flowed through it the same afternoon that he pulled America out of the Paris climate accords.

That means, of course, that renewables advocates need to emphasize the jobs that will be created as we move towards sun and wind—and since those jobs aren’t always going to be in the same places as the fossil fuel ones they replace, a just transition for displaced workers is needed. There are already far more Americans employed in the solar industry than in the coal fields, and we’re still near the start of the conversion: Sanders and Merkley produced studies to show their federal 100 percent bill, beyond its generous transition benefits, would produce three million net new jobs over the coming decades.

Environmental justice advocates, who have been at the front of the climate fight, are quick to point out that a push for renewables needs to means more than EV charging stations and solar panels on the roofs of people who can afford big roofs. If a city announces it’s going 100% renewable and then keeps buying diesel buses (or stops buying buses altogether, relying on Lyft and Uber to create an alternate transit system), then it would be an empty boast.

“America’s twisted politics may slow the transition to renewables, but other countries are now pushing the pace.”

Meanwhile, renters need ways to join the renewable revolution, just like homeowners. None of it’s easy. As Jacqui Patterson, who heads the NAACP’s environmental justice work, says: “people now lose their lives for not being able to pay for electricity—they’re burning down their houses by using candlelight, or because their oil has run out and they have to use heaters, or they’re on respirators and their electricity goes out. So as we’re transitioning to renewables, we need to make sure there are not unintended consequences in term of rate increases–for those communities ‘just transition’ means their bills don’t fluctuate upwards. Ideally their bills would go down.” In the best of worlds, she adds, “just transition means they’re owning part of the energy infrastructure. They’re not just a consumer writing a check every month, but they see now a chance to own part of that infrastructure.”

There are signs that’s starting to happen. When Sanders and Merkley announced their federal legislation in April of 2017, leaders of groups like Green for All and Brooklyn’s feisty UPROSE were featured speakers; one of the most impassioned endorsements came from Mustafa Ali of the Hip Hop Caucus: “This act gives our country an opportunity to embrace a just transition, honor the innovation and hard work that exists in communities that are often overlooked and forgotten, and revitalize communities of color, low income communities and indigenous populations,” he said.

In May of 2017, the Wallace Global Fund, one of the big environmental philanthropies, pointedly awarded the Standing Rock Sioux a million dollars to build renewable energy on the reservation, a fitting commemoration to the bravery of protesters who tried to hold the Dakota pipeline at bay and a reminder that private charities will need to play a role in this transition as well. But the political battle will be hard-fought: the New York Times reported last year that the Koch Brothers have begun to aggressively (and cynically) court minority communities, arguing that they “benefit the most from cheap and abundant fossil fuels.”

America’s twisted politics may slow the transition to renewables, but other countries are now pushing the pace. In July of 2017, for instance, the Chinese announced that Qinghai Province—a territory the size of Texas—had gone a week relying on 100% renewable energy, a test of grid reliability designed to show that the country could continue its record-breaking pace of wind and solar installation. (About the same time the Chinese released aerial photos of their newest giant wind farm—which seen from above depicts a cheerful black-and-white panda).

China is not alone:

- One Friday in April of 2017, Great Britain managed to meet its power demands without burning a lump of coal for the first time since the launch of the Industrial Revolution.

- Solar production has grown six-fold since 2014 in Chile

- Santiago announced that starting this year, their subway system will be running entirely on the sun.

- Since January 1 of 2017, Holland’s train system has been entirely powered by the wind.

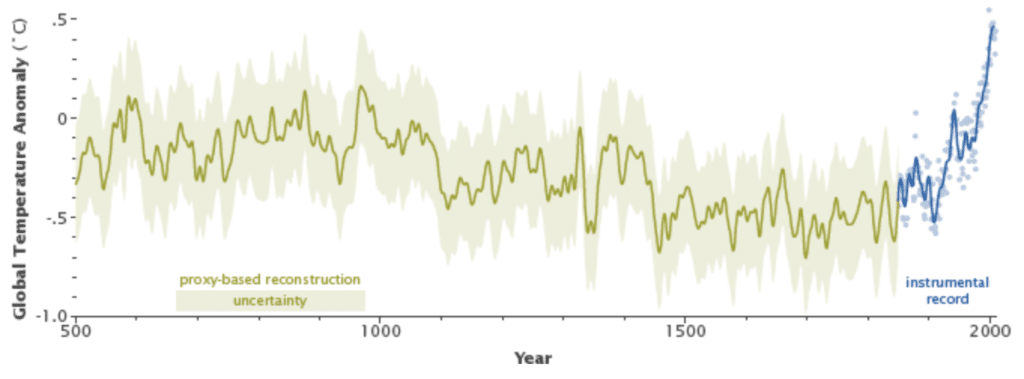

These are all good signs—but set against the rapid disintegration of ice caps and the record global temperatures set each of the last three years they also seem like too little. It’s going to take a deeper level of commitment—including turning the federal government from an obstacle to an advocate over the next election cycles. That’s doable precisely because the idea of renewable energy is so popular.

“There’s a few reasons why 100% renewable is working—why it’s such a powerful idea,” says Mike Brune, executive director of the Sierra Club. “People have agency, for one. People who are outraged, alarmed, depressed, filled with despair about climate change—they want to make a difference in ways they can see, so they’re turning to their backyards. Turning to their city, their state, their university. And, it’s exciting—it’s a way to address this not just through dread with something that sparks your imagination.”

Sometimes, he said, all environmentalists have to rally together to work on the same thing: the Keystone pipeline, the Paris accord. “But in this case the politics is as distributed as the solution—it’s people working on thousands of examples of the one idea.” An idea whose time has come.