After a deadly week of shootings and protests, racial tensions are higher than they’ve been in years. Former CEO and president of the NAACP Ben Jealous joins CBSN to discuss the state of race relations in the U.S.

After a deadly week of shootings and protests, racial tensions are higher than they’ve been in years. Former CEO and president of the NAACP Ben Jealous joins CBSN to discuss the state of race relations in the U.S.

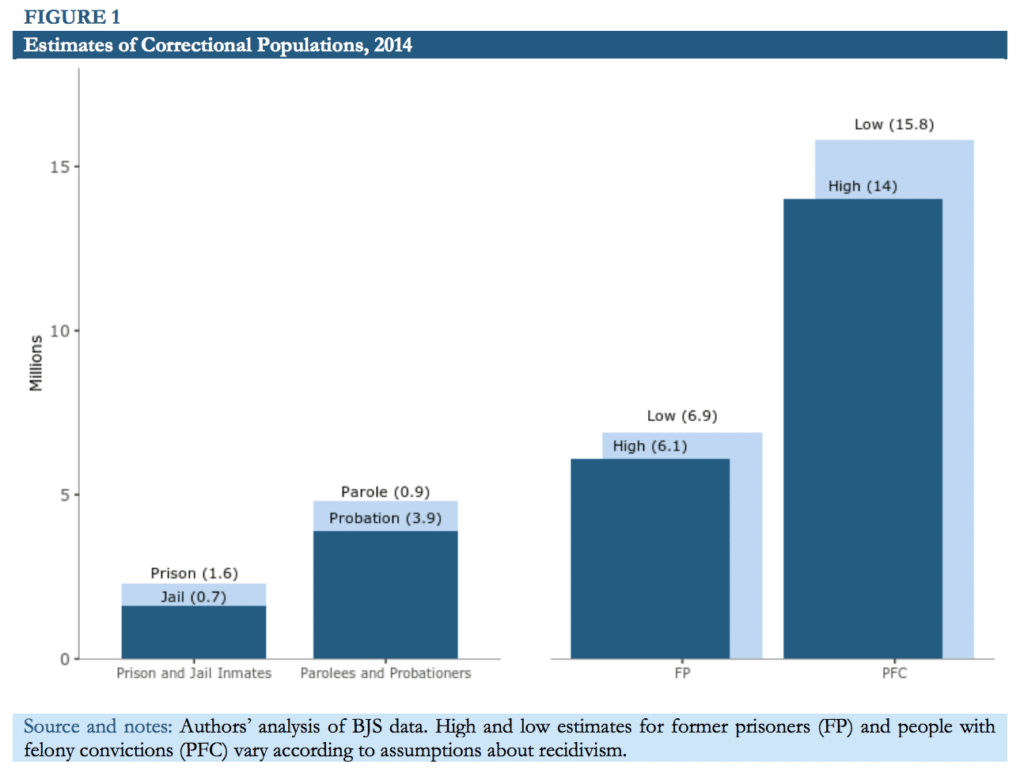

Despite modest declines in recent years, the large and decades-long blossoming of the prison population ensure that it will take many years before the United States sees a corresponding decrease in the number of former prisoners. Using data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), this report estimates that there were between 14 and 15.8 million working-age people with felony convictions in 2014, of whom between 6.1 and 6.9 million were former prisoners.

Prior research has shown the adverse impact that time in prison or a felony conviction can have on a person’s employment prospects. In addition to the stigma attached to a criminal record, these impacts can include the erosion of basic job skills, disruption of formal education, and the loss of social networks that can improve job-finding prospects. Those with felony convictions also face legal restrictions that lock them out of many government jobs and licensed professions.

Assuming a mid-range 12 percentage-point employment penalty for this population, this report finds that there was a 0.9 to 1.0 percentage-point reduction in the overall employment rate in 2014, equivalent to the loss of 1.7 to 1.9 million workers. In terms of the cost to the economy as a whole, this suggests a loss of about $78 to $87 billion in annual GDP.

Some highlights of this study include:

This paper updates earlier CEPR research that also examined the impact of former prisoners and those with felony convictions on the economy.

Introduction

The number of prisoners in the United States has grown dramatically over the past 40 years. In 1980, there were 503,600 people in prisons or jails at the federal, state and local level. By the end of 2014, this number had ballooned to 2,224,400, and an additional 4,708,100 people were on parole or probation at that time. These figures translate to about 1 in 110 adults behind bars and about 1 in 52 adults on parole or probation. Despite small decreases in the share of people in prison or jail in recent years, the United States still has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world, second only to Seychelles.

While this growth in the overall number of prisoners, parolees, and probationers has been documented over time, estimates of the total number of former prisoners and people with felony convictions have been rare. This report builds off of prior CEPR research examining the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions. It estimates both the size (see Figure 1) and impact of this population on the U.S. labor market.

Time in prison, jail, or even a felony conviction can have a tremendous impact on the lives of former prisoners and people with felony convictions. A criminal record can negatively affect prospects for employment, education, public assistance, and even civic participation by making many people with felony convictions ineligible to vote. Often it is not just the former prisoner or person with felony convictions impacted; the well-being of their families is often threatened. This analysis focuses on the negative effect on the employment prospects of former prisoners and people with felony convictions and the implications for the labor market.

The calculations in this paper indicate that in 2014, the year for which there is the latest available data, the impediments to employment faced by former prisoners and people with felony convictions meant a loss of about 1.7 to 1.9 million workers. This was equal to a roughly 0.9 to 1.0 percentagepoint reduction in the overall employment rate, and a loss of between $78 and $87 billion in GDP.

The uptick in the U.S. incarceration rate and the number of former prisoners and people with felony convictions in the U.S. are a reflection not of a crime rate spiraling out of control, but of significant and often unnecessary changes in the criminal justice system. For example, both violent and property crime rates are much lower today than they were in the 1980s when the incarceration rate began to increase rapidly. Rather, much of the increase in incarceration is due to strict and often harsh sentencing probabilities and sentence lengths. This explosion in the number of people in U.S. prisons and jails has rightly been characterized by Gottschalk as the metastasizing carceral state.

In recent years, there has been broad acknowledgement of the need for reform of the criminal justice system, due in part to the ways in which it has directly contributed to the increase in mass incarceration and the collateral costs that have resulted. Calls to address the severity of policies such as the War on Drugs and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 have become louder and more critical, from the vocal protests of Black Lives Matter and others to executive orders and legislation from President Obama as well as both Democrats and Republicans in Congress. Estimates of the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions like the one offered here can play a role in this discussion by demonstrating the negative impact of aggressive and often ineffective incarceration policies on the overall economy.

Estimating the Number of Former Prisoners and People with Felony Convictions

There are no publicly available data on the exact size or composition of the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions. In lieu of that, this paper provides an indirect estimate of the former prisoner population, and uses it to estimate the size and composition of the population of people with felony convictions.

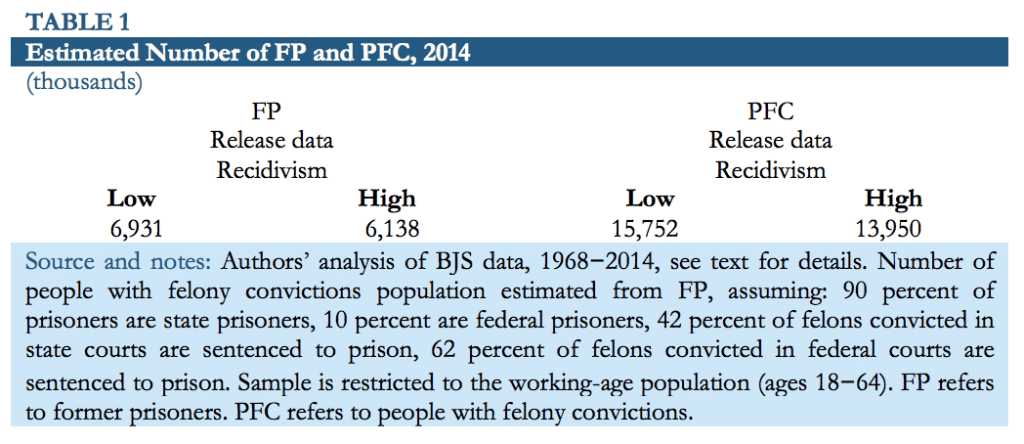

Table 1 displays estimates of the number of former prisoners and people with felony convictions in 2014. These estimates are based on an analysis of Bureau of Justice Statistics data that count the number of prisoners released each year from 1968 to 2014. Assuming that the age and gender distributions of released prisoners are the same as the overall prison population, this report “tracks” each yearly cohort of released prisoners over time. As it is only concerned with the working-age population (ages 18 to 64), it allows former prisoners to age out once they reach age 65. Then, agegroup-specific return-to-prison recidivism rates are applied to isolate the former prisoners who do not return to prison. Here, there is use of both a low and a high measure of the recidivism rate to account for returns that occur after three years.

Next, an estimate of age-specific death rates are applied, adjusting up accordingly, to account for the high-risk population of this study. 14 The first two columns of Table 1 imply that the former prisoner population in the U.S. in 2014 was between 6.1 million (using a high recidivism rate) and 6.9 million (using a low recidivism rate). See the Appendix for further details on this estimation technique.

In the past, researchers have attempted to estimate the former prisoner population. This paper uses the same methods of Schmitt and Warner (2010). Their report focused on the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions in 2008, and their results showed that there were between 5.4 and 6.1 million former prisoners of working age in 2008. Forecasts made by Bonczar (2003) imply that there would be about 5.7 million former prisoners in 2008 and 6.2 million former prisoners in 2010. Extending the methods from this report back to 2010, there were approximately between 5.6 and 6.3 million former prisoners in 2010. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there have not been any attempts to estimate the size or characteristics of the former prisoner population since 2010. However, the methods used in this paper are the same as those used by Schmitt and Warner (2010), which had results that were broadly consistent with the other estimates mentioned.

The final two columns of Table 1 show estimates of the number of people with felony convictions.

Again, there are no direct estimates of this population, but this report uses administrative data on the percent of felons sentenced to prison, in addition to the estimates of the former prisoner population presented in this paper to arrive at estimates of the number of people with felony convictions. About 44 percent of felons are sentenced to prison. The approach used in this paper estimates that there were between 14.0 million and 15.8 million people with felony convictions in 2014. In their earlier report using the same methods, Schmitt and Warner (2010) estimated that there were between 12.3 million and 13.9 million people with felony convictions in 2008.

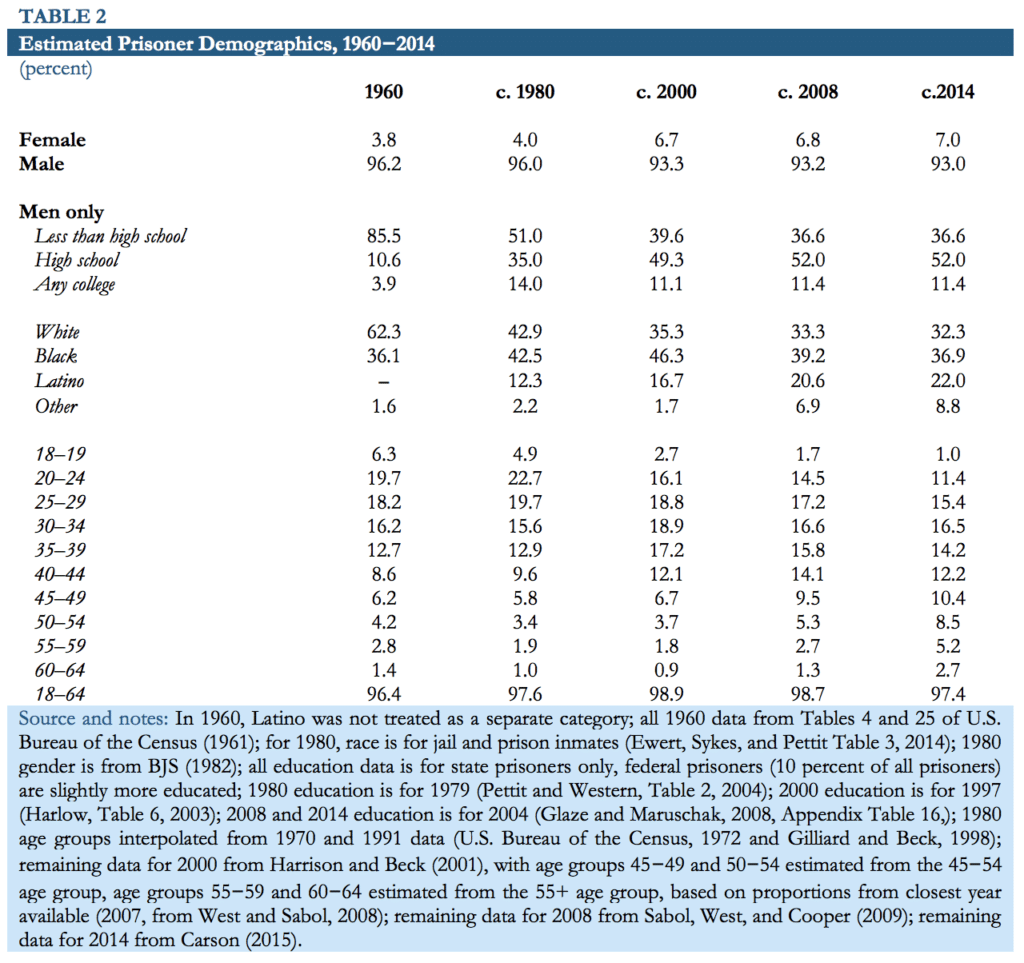

In addition to estimates of the number of former prisoners and people with felony convictions, another goal of this paper is to determine their demographic characteristics. To estimate these characteristics, this report first uses the demographic characteristics of current prisoners for selected years and applies these estimates to the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions. Table 2 shows various characteristics of the prisoner population for selected years from 1960 to 2014. For all years, the male prisoner population greatly outnumbered the female prisoner population, with men making up at least 93 percent of the population in all years displayed. In 2014, men made up 93.0 percent of the prison population, and this percentage has remained mostly steady since 2000.

Education level, race, and age breakdowns are also displayed for the male prison population. Male prisoners are considerably less educated than the overall male working-age population, with over 85 percent having a high school degree or less. In 2014, about 43 percent of the overall working-age male population had a high school degree or less. During the same year, 97.4 percent of male prisoners were of working age, and 31.9 percent were between the ages of 25 and 34. Also in 2014 36.9 percent of male prisoners were Black, 32.3 percent were white, and 22.0 percent were Latino.

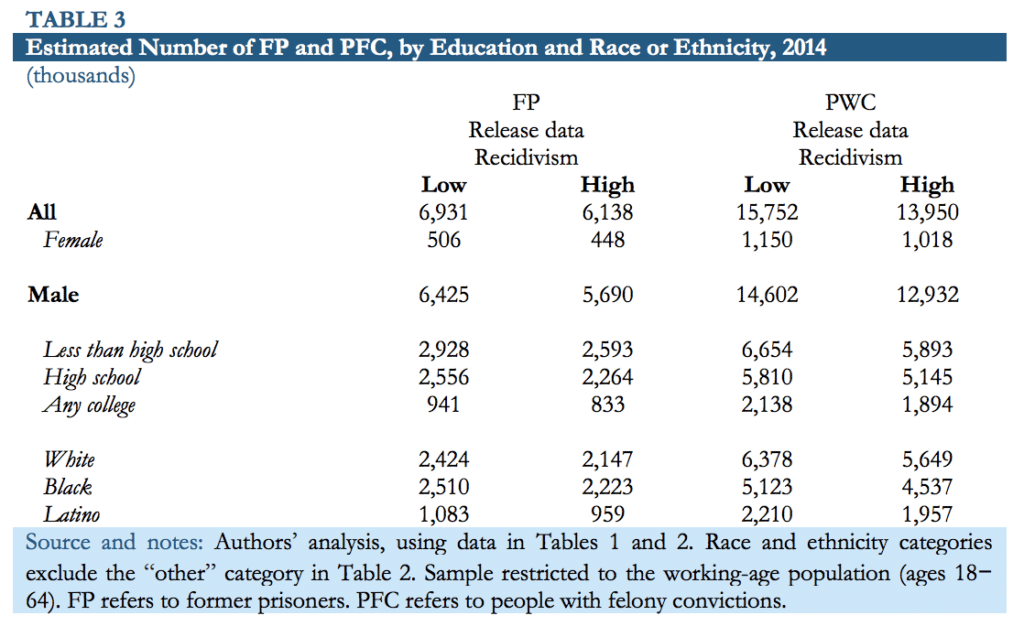

Using the data from Table 2 on the prisoner population, estimates of the demographic characteristics of the entire population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions were created, adjusting for racial differences in recidivism rates and imprisonment rates conditional on felony conviction. Table 3 displays these estimates. According to this data, in 2014 between 448,000 and 506,000 former prisoners were women, and between 1.0 and 1.2 million people with felony convictions were women. Between 5.7 and 6.4 million former prisoners were men, and between 12.9 and 14.6 million people with felony convictions were men. Among male former prisoners, between 2.6 and 2.9 million had less than a high school degree.

There were notable differences in the racial composition of the population of male former prisoners and people with felony convictions. There were more Blacks than whites in the former prisoner population, but there were over 1 million more whites than Blacks in the population of people with felony convictions. This is the result of disparate sentencing rates between the two races. About 49 percent of Black felons are sentenced to prison, while only about 38 percent of white felons are sentenced to prison.19 In 2014, there were approximately between 2.1 and 2.4 million white male former prisoners and between 5.6 and 6.4 million white males with felony convictions. During the same year, there were between 2.2 and 2.5 million Black male former prisoners, and between 4.5 and 5.1 million Black males with felony convictions in the United States.

The Effects of Imprisonment and Felony Conviction on Subsequent Employment

A large body of evidence demonstrates that prison time and felony convictions can have a lasting and profound effect on future prospects for employment. In addition to the stigma attached to a criminal record, these impacts include the erosion of basic job skills, disruption of formal education, loss of networks that can improve job-finding prospects, or deterioration of “people skills.” Schmitt and Warner’s review of longitudinal surveys, employer surveys, audit studies, aggregated geographic data, and administrative data suggests that time behind bars can have a significant effect on the employment of those with prison experience or felony convictions. Similarly, a recent review of the literature by Travis, Western and Redbum (2014) discussed the potential supply-side effects and added that “repeated encounters with rejection may lead to cynicism and withdrawal from formal labor market activity.” And while much of the literature on the effects of incarceration focuses on men, Decker, Spohn, Ortiz and Hedberg (2014) find in their study that incarceration has a negative impact on employment for women as well. These hurdles to employment can create an unfortunate cycle as Berg and Huebner (2011) note that post–incarceration employment significantly lowers the chances of recidivism.

Assessment of Employment Effects

The employment effects of incarceration or a felony conviction vary based on the research techniques used, the population researched, and the metrics that describe the employment impact. For the most part, the research shows a moderate to large impact on the employment levels of former prisoners and people with felony convictions. However, this report is concerned with an estimate of the impact of the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions on the employment levels of all working-age adults, which is somewhat outside the scope of much of the research on incarceration and employment. Longitudinal surveys of individuals capture much of the data necessary for the analysis in this paper and typically yield moderate to large effects on employment levels. Employer surveys and audit studies also show a large impact on employment levels but are less useful for this present analysis. Aggregate state-level data, though less-directly applicable, show small to moderate effects. Administrative studies, while more in line methodologically with longitudinal studies, have technical difficulties and produce results that are inconsistent with other available data.

To better estimate the impact on employment levels while considering these methodological differences, this paper uses the three separate estimates employed by Schmitt and Warner (2010). The estimates examine low-, medium-, and high-effects scenarios to develop estimates of the employment effects of incarceration. Like Schmitt and Warner:

“In the low-effects scenario, we assume that ex-prisoners or ex-felons pay an employment penalty of five percentage points (roughly consistent with the largest effects estimated using administrative data and the lower range of effects estimated using the aggregate data and survey data). In the mediumeffects scenario, we assume that the employment penalty faced by ex-prisoners and ex-felons is 12 percentage points, which is consistent with the bulk of the survey-based studies. In the high-effects scenario, we assume that the employment penalty is 20 percentage points, which is consistent with the largest effects estimated in the survey-based studies, as well as, arguably, the findings of the employer surveys and audit studies.”

Estimating the Impact of Former Prisoners and People with Felony Convictions on Total Employment and Output

Here, this report estimates the effect of the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions on total employment and output. To do so, this report uses the estimates of the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions and the outside estimates of the employment penalty faced by those with prison experience or a felony conviction from the previous two sections of this paper.

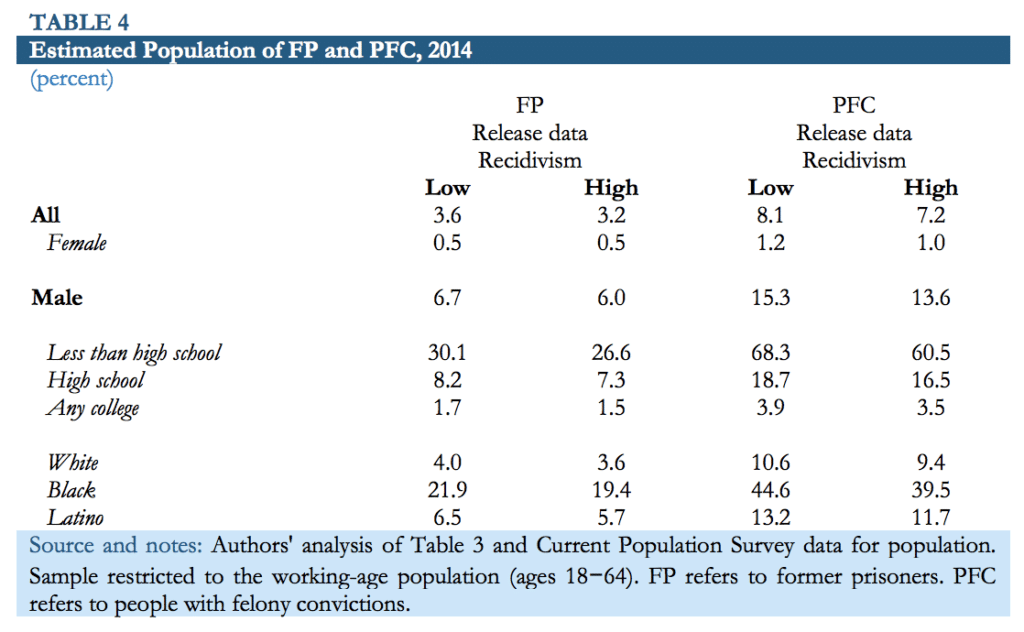

First, the size and demographic characteristics of the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions from Table 3 are compared to the overall civilian, non-institutional workingage population. Table 4 displays estimates of the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions as a share of the total working-age population in 2014. Overall, former prisoners were between 3.2 and 3.6 percent of the non-institutional working-age population. People with felony convictions were between 7.2 and 8.1 percent. As with those currently behind bars, former prisoners and people with felony convictions are much more likely to be men than women. In 2014, an estimated 6.0 to 6.7 percent of the working-age male population were former prisoners, and between 13.6 and 15.3 percent were people with felony convictions. On the other hand, between 0.45 and 0.51 percent of working-age women were former prisoners, and between 1.0 and 1.2 percent were people with felony convictions.

There were also notable differences by education level and race, although these estimates are less precise than those above. Between 26.6 and 30.1 percent of men with less than a high school degree were former prisoners, and between 60.5 and 68.3 percent were people with felony convictions. By contrast, only between 1.5 and 1.7 percent of men with any college experience were former prisoners and between 3.5 and 3.9 percent were people with felony convictions. Black men were more likely than their white or Latino counterparts to be former prisoners or people with felony convictions. Between 19.4 and 21.9 percent of Black men were former prisoners, and between 39.5 and 44.6 percent were people with felony convictions.

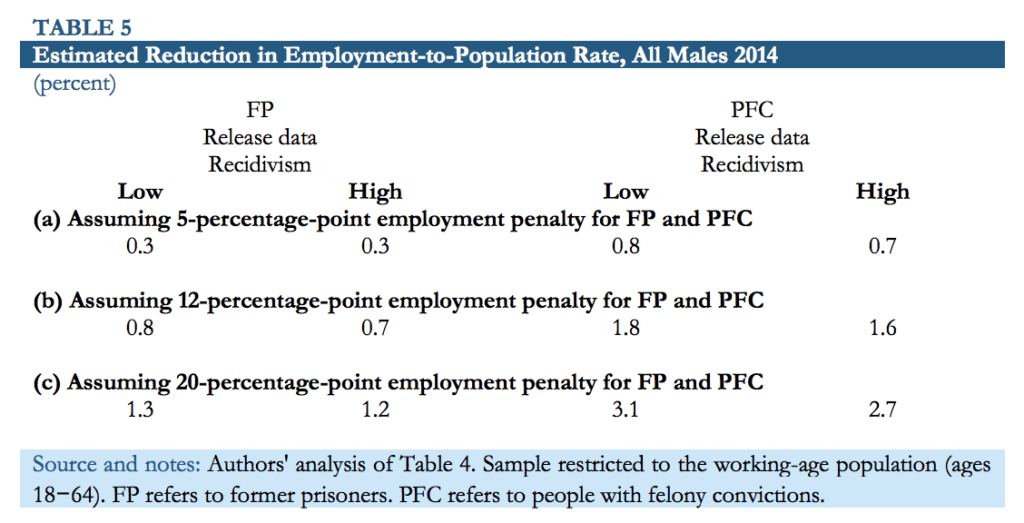

The calculations in Table 4 are then used to determine the reduction in the overall employment rate that occurs as a result of the employment penalty for former prisoners and people with felony convictions. Table 5 shows the results of this exercise for men. Three separate sets of measures are displayed. The first assumes a low, 5 percentage-point employment penalty compared to a similar worker with no prison experience or felony conviction. The second set of measures assumes a medium, 12 percentage-point employment penalty, and the last set assumes a high, 20 percentagepoint employment penalty.

Assuming a low employment penalty of 5 percentage points, the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions lowered the employment rate of men by between 0.3 and 0.8 percentage points in 2014. Assuming a medium, 12 percentage-point employment penalty, the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions lowered the employment rate of men by between 0.7 and 1.8 percentage points. With a high employment penalty of 20 percentage points, this population lowered the employment rate of men by between 1.2 and 3.1 percentage points.

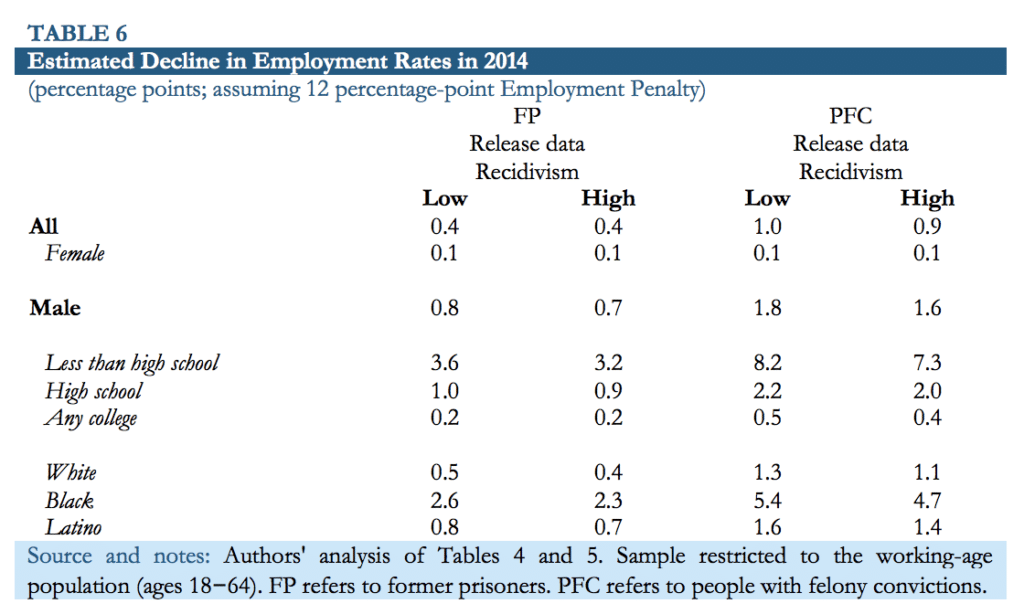

Table 6 displays the estimated decline in overall employment rates in 2014, with various demographic breakdowns. These estimates assume a medium, 12 percentage-point employment penalty for former prisoners and people with felony convictions. They show that the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions reduced the overall employment of the working-age population by between 0.4 and 1.0 percentage points. The impact was particularly large for Black men and men with less than a high school degree. The population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions lowered the employment rates of Black men by between 2.3 and 5.4 percentage points. This population also lowered the employment rates of men with less than a high school degree by between 3.2 and 8.2 percentage points.

The results presented in this paper show how contact with the criminal justice system in the form of a felony conviction or imprisonment can affect the future employment prospects of former prisoners and people with felony convictions. In addition to the likely large reductions in personal earnings as a result of these employment penalties, the economy as a whole suffers from a reduction in output. More specifically, this report estimates that the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions cost the U.S. about 0.45 to 0.5 percentage points of GDP in 2014, or about $78.1 to $86.7 billion.

Conclusion

This paper examines the labor market impact of the growing number of individuals who have been imprisoned or have felony convictions. The findings presented in this paper show that, in 2014, overall employment rates were 0.9 to 1.0 percentage points lower as a result of the employment penalty faced by the large population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions. For men, their employment rate was 1.6 to 1.8 percentage points lower and for men with less than a high school degree, their employment rate was 7.3 to 8.2 percentage points lower.

However, it is not just the individual that suffers; the impact is felt across the U.S. labor market. In terms of GDP, the calculations in this report suggest that the population of former prisoners and people with felony convictions led to a loss of $78 to $87 billion in GDP in 2014. While there has recently been a push from advocates and policy-makers alike to re-examine sentencing policy and practice, the negative impacts on former prisoners and people with felony convictions themselves and the economy as a whole will grow in scale unless the burgeoning reform trend continues and accelerates.

This report has been altered for publication on The Sanders Institute website. To read the full report with the Appendix click here.

Brexit is a watershed event that signals the need for a new kind of globalization, one that could be far superior to the status quo that was rejected at the British polls. What is required, above all, is a shift from a strategy of war to one of sustainable development.

The Brexit vote was a triple protest: against surging immigration, City of London bankers, and European Union institutions, in that order. It will have major consequences. Donald Trump’s campaign for the US presidency will receive a huge boost, as will other anti-immigrant populist politicians. Moreover, leaving the EU will wound the British economy, and could well push Scotland to leave the United Kingdom – to say nothing of Brexit’s ramifications for the future of European integration.

Brexit is thus a watershed event that signals the need for a new kind of globalization, one that could be far superior to the status quo that was rejected at the British polls.

At its core, Brexit reflects a pervasive phenomenon in the high-income world: rising support for populist parties campaigning for a clampdown on immigration. Roughly half the population in Europe and the United States, generally working-class voters, believes that immigration is out of control, posing a threat to public order and cultural norms.

In the middle of the Brexit campaign in May, it was reported that the UK had net immigration of 333,000 persons in 2015, more than triple the government’s previously announced target of 100,000. That news came on top of the Syrian refugee crisis, terrorist attacks by Syrian migrants and disaffected children of earlier immigrants, and highly publicized reports of assaults on women and girls by migrants in Germany and elsewhere.

In the US, Trump backers similarly rail against the country’s estimated 11 million undocumented residents, mainly Hispanic, who overwhelmingly live peaceful and productive lives, but without proper visas or work permits. For many Trump supporters, the crucial fact about the recent attack in Orlando is that the perpetrator was the son of Muslim immigrants from Afghanistan and acted in the name of anti-American sentiment (though committing mass murder with semi-automatic weapons is, alas, all too American).

Warnings that Brexit would lower income levels were either dismissed outright, wrongly, as mere fearmongering, or weighed against the Leavers’ greater interest in border control. A major factor, however, was implicit class warfare. Working-class “Leave” voters reasoned that most or all of the income losses would in any event be borne by the rich, and especially the despised bankers of the City of London.

Americans disdain Wall Street and its greedy and often criminal behavior at least as much as the British working class disdains the City of London. This, too, suggests a campaign advantage for Trump over his opponent in November, Hillary Clinton, whose candidacy is heavily financed by Wall Street. Clinton should take note and distance herself from Wall Street.

In the UK, these two powerful political currents – rejection of immigration and class warfare – were joined by the widespread sentiment that EU institutions are dysfunctional. They surely are. One need only cite the last six years of mismanagement of the Greek crisis by self-serving, shortsighted European politicians. The continuing eurozone turmoil was, understandably, enough to put off millions of UK voters.

The short-run consequences of Brexit are already clear: the pound has plummeted to a 31-year low. In the near term, the City of London will face major uncertainties, job losses, and a collapse of bonuses. Property values in London will cool. The possible longer-run knock-on effects in Europe – including likely Scottish independence; possible Catalonian independence; a breakdown of free movement of people in the EU; a surge in anti-immigrant politics (including the possible election of Trump and France’s Marine Le Pen) – are enormous. Other countries might hold referendums of their own, and some may choose to leave.

In Europe, the call to punish Britain pour encourager les autres – to warn those contemplating the same – is already rising. This is European politics at its stupidest (also very much on display vis-à-vis Greece). The remaining EU should, instead, reflect on its obvious failings and fix them. Punishing Britain – by, say, denying it access to Europe’s single market – would only lead to the continued unraveling of the EU.

So what should be done? I would suggest several measures, both to reduce the risks of catastrophic feedback loops in the short term and to maximize the benefits of reform in the long term.

First, stop the refugee surge by ending the Syrian war immediately. This can be accomplished by ending the CIA-Saudi alliance to overthrow Bashar al-Assad, thereby enabling Assad (with Russian and Iranian backing) to defeat the Islamic State and stabilize Syria (with a similar approach in neighboring Iraq). America’s addiction to regime change (in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria) is the deep cause of Europe’s refugee crisis. End the addiction, and the recent refugees could return home.

Second, stop NATO’s expansion to Ukraine and Georgia. The new Cold War with Russia is another US-contrived blunder with plenty of European naiveté attached. Closing the door on NATO expansion would make it possible to ease tensions and normalize relations with Russia, stabilize Ukraine, and restore focus on the European economy and the European project.

Third, don’t punish Britain. Instead, police national and EU borders to stop illegal migrants. This is not xenophobia, racism, or fanaticism. It is common sense that countries with the world’s most generous social-welfare provisions (Western Europe) must say no to millions (indeed hundreds of millions) of would-be migrants. The same is true for the US.

Fourth, restore a sense of fairness and opportunity for the disaffected working class and those whose livelihoods have been undermined by financial crises and the outsourcing of jobs. This means following the social-democratic ethos of pursuing ample social spending for health, education, training, apprenticeships, and family support, financed by taxing the rich and closing tax havens, which are gutting public revenues and exacerbating economic injustice. It also means finally giving Greece debt relief, thereby ending the long-running eurozone crisis.

Fifth, focus resources, including additional aid, on economic development, rather than war, in low-income countries. Uncontrolled migration from today’s poor and conflict-ridden regions will become overwhelming, regardless of migration policies, if climate change, extreme poverty, and lack of skills and education undermine the development potential of Africa, Central America and the Caribbean, the Middle East, and Central Asia.

All of this underscores the need to shift from a strategy of war to one of sustainable development, especially by the US and Europe. Walls and fences won’t stop millions of migrants fleeing violence, extreme poverty, hunger, disease, droughts, floods, and other ills. Only global cooperation can do that.

This video from Ted-Ed describes the difference between migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees:

Migrants: “Refers to people who leave their countries for reasons not related to persecution such as searching for better economic opportunities or leaving drought ridden areas in search of better circumstances.”

Refugees: “International law, rightly or wrongly, only recognizes those fleeing conflict and violence as refugees.”

Asylum Seeker: “Once in a new country, the first legal step for a displaced person is to apply for asylum. At this point they are an asylum seeker and not officially recognized as a refugee until the application has been accepted.”

The video also describes the experiences of many refugees from being displaced from their homes through violence, through their stays in refugee camps, applications for asylum, and then relocation in other countries.

Nothing is more important to me, and nothing was more important to our founding fathers, than freedom of religion.

The freedom of every individual to follow the spiritual path of our choice or to follow no religion at all. This freedom is enshrined in our constitution, in our Bill of Rights, which every member of Congress takes an oath to protect. And which so many heroes have given their lives to defend.

As a soldier I served in the Middle East, where I experienced first hand not only the cost of war, but I came to understand the cause of the endless conflicts that persist today.

The cause of these endless conflicts lies in the ambitions of various religious sects to control the levers of government, and to dominate those who adhere to other religious beliefs.

Shia and Sunni Muslims are vying against each other to establish theocracies or caliphates led by their religious leaders.

The Shia theocratic dictatorship of Iran is supporting the cause of Shias, while the Sunni theocracies like Saudi Arabia and others in the Gulf States are backing the Sunni fighters and terrorists like ISIS and Al Qaeda.

In the meantime, Christians, Yazidis, Sufis, and other Muslim and non-Muslim minority religious groups face genocide.

People in the middle east, people everywhere, want peace. But unfortunately too many fail to recognize that that lasting peace can only be found with pluralistic secular government.

What is lacking in the world is “Aloha.” Now, Aloha is not just a word that means hello and goodbye. It’s a word with a deeper and far more powerful meaning. It’s a word that really means that you have a deep respect and love for others regardless of the color of our skin, where we come from, or the spiritual path that we may follow.

Whether we’re hindus, christians, atheists, buddhists, agnostic, or anything else, that we respect and love each other as brothers and sisters. This is the essence of Aloha.

When we have aloha for others, we will naturally come to respect that every individual has free will. And thus, the freedom to follow the spiritual path of our choice or no spiritual path at all. This recognition of our individual free will and our commitment to individual freedom is the essence of what it means to be an American. We must remember that this nation was founded by people fleeing religious persecution. Risking everything to find a place to be free to worship as they chose or not to worship at all. In the original articles of our constitution drafted by our founding fathers, Article 6 clearly states that quote no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or any public trust under the United States.

Each of us wants to be free. But if we want to be free we also need to appreciate that others also desire the same thing. If we don’t want others to trample on our individual free will, than we must be careful not to trample on the free will of others. The great Chinese sage Confucius once said “don’t do to others what you don’t want done to yourself.” Jesus Christ made the same point. “Do Unto others as you would have done unto you.” So if I don’t want someone else to force me to follow their spiritual path or non-spiritual path, then I too must not force them to follow the path I have chosen for myself. It is when a society fails to respect an individual’s freedom of choice that this society inevitably ends up in great darkness and suffering. And it’s unfortunate that there are billions of people around the world who live in such darkness. Who live in worlds where individual freedom of conscious and religion do not exist. Where people who are followers of the so called wrong religion or have no religion at all are treated as lesser human beings. Are discriminated against, oppressed, forced to pay extra taxes, forced from their homes or their lands, or, worse yet, raped or killed.

A pluralist secular government is the only way to ensure that all individuals have the freedom to follow the religious or non-religious path of our choice.

Recently in Bangladesh, a secular blogger named Nazimuddin Samad posted an article criticising organized religion. He was hacked to death by a crowd of men wielding machetes and yelling Allah Akbar. A Hindu temple in Northern Bangladesh was attacked with grenades and small arms fire. And the priest, Jogeshwar Roy had his throat slit. Police arrested three suspects tied to Islamist Jihadists. Just last month, Khurram Zaki, a prominent Pakistani journalist and human rights activists was gunned down by the Taliban while dining at a Karachi restaurant. Why? Because he was one of many Muslims courageously advocating for a pluralistic, tolerant secular, Pakistan. We must stand with such freedom loving Muslims and followers of all other religious and atheists who are committed to pluralism and individual free choice. These brave souls are calling for a pluralistic society built on religious freedom and are fighting a desperate battle against extremists who are financially supported by theocracies like Saudi Arabia and Iran. We must stand with those in Bangladesh and other parts of the world who are building coalitions of Christians and Buddhists and Hindus, atheists, secularists, risking their lives to advocate for pluralism and secularism. Furthermore, we must recognize that here at home our own nation is not immune to religious bigotry. As we stand here at the foot of the lincoln memorial, we can remember how Abraham Lincoln was attacked with accusations that he was not a christian. When John F. Kennedy ran for president his political opponents tried to foment religious bigotry based on his catholicism. When Barack Obama ran for President in 2007 people accused him of being muslim as though that might somehow disqualify him from being president. When Mitt Romney ran for president, there were direct attacks against his Mormon religion. When I first ran for Congress in 2012 my Republican opponent said in a CNN interview that I should not be allowed to serve in Congress because my religion quote does not align with the Constitutional foundation of the U.S. government. Just last year, Missouri State auditor Tom Schweich committed suicide after political opponents launched a malicious anti-semitic whisper campaign against him saying he was jewish.

The message that we see in each of these situation is simple. That you will be punished politically for being of the so called wrong religion. There is nothing more un-American than this.

We have a great challenge that lies before us. Let us stand proudly as Americans. As defenders of our constitution. As defenders of freedom. Let us be inspired by the vision put forward by our nation’s founders, and challenge those fomenting religious bigotry to do the same. Rather than pour fuel on the fire of darkness, divisiveness, and hatred, let us bring the light found in the aloha spirit. Respect and love for everyone, irrespective of religion, race, gender, any of the external differences, to our lives, our families, our country, and the world. Let us be inspired by the likes of Muhammed Ali, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, as we join hands working toward the day when every young American, whether they are Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, Christian, Jew, Muslim, Humanist or Atheist, can live without fear. With the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that our forefathers envisioned for all of us. Let us confront hatred with love. Confront bigotry with Aloha. Confront fear with truth. Let us truly live Aloha in our actions, in our words, and in our hearts.

Thank you very much. Aloha.

Barack Obama’s visit to Cuba is the first by a US president since Calvin Coolidge went in 1928. American investors, expat Cubans, tourists, scholars, and scam artists will follow in Obama’s wake. Normalization of the bilateral relationship will pose opportunities and perils for Cuba, and a giant test of maturity for the United States.

The Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro 57 years ago was a profound affront to the US psyche. Since the founding of the US, its leaders have staked a claim to American exceptionalism. So compelling is the US model, according to its leaders, that every decent country must surely choose to follow America’s lead. When foreign governments are foolish enough to reject the American way, they should expect retribution for harming US interests (seen to align with universal interests) and thereby threatening US security.

With Havana a mere 90 miles from the Florida Keys, American meddling in Cuba has been incessant. Thomas Jefferson opined in 1820 that the US “ought, at the first possible opportunity, to take Cuba.” It finally did so in 1898, when the US intervened in a Cuban rebellion against Spain to assert effective US economic and political hegemony over the island.

In the fighting that ensued, the US grabbed Guantánamo as a naval base and asserted (in the now infamous Platt Amendment) a future right to intervene in Cuba. US Marines repeatedly occupied Cuba thereafter, and Americans quickly took ownership of most of Cuba’s lucrative sugar plantations, the economic aim of America’s intervention. General Fulgencio Batista, who was eventually overthrown by Castro, was the last of a long line of repressive rulers installed and maintained in power by the US.

The US kept Cuba under its thumb, and, in accordance with US investor interests, the export economy remained little more than sugar and tobacco plantations throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Castro’s revolution to topple Batista aimed to create a modern, diversified economy. Given the lack of a clear strategy, however, that goal was not to be achieved.

Castro’s agrarian reforms and nationalization, which began in 1959, alarmed US sugar interests and led the US to introduce new trade restrictions. These escalated to cuts in Cuba’s allowable sugar exports to the US and an embargo on US oil and food exports to Cuba. When Castro turned to the Soviet Union to fill the gap, President Dwight Eisenhower issued a secret order to the CIA to topple the new regime, leading to the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, in the first months of John F. Kennedy’s administration.

Later, the CIA was given the green light to assassinate Castro. In 1962, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev decided to forestall another US invasion – and teach the US a lesson – by surreptitiously installing nuclear missiles in Cuba, thereby triggering the October 1962 Cuban missile crisis, which brought the world to the brink of nuclear annihilation.

Through dazzling restraint by both Kennedy and Khrushchev, and no small measure of good luck, humanity was spared; the Soviet missiles were removed, and the US pledged not to launch another invasion. Instead, the US doubled down on the trade embargo, demanded restitution for nationalized properties, and pushed Cuba irrevocably into the Soviet Union’s waiting arms. Cuba’s sugar monoculture remained in place, though its output now headed to the Soviet Union rather than the US.

The half-century of a Soviet-style economy, exacerbated by the US trade embargo and related policies, took a heavy toll. In purchasing-power terms, Cuba’s per capita income stands at roughly one-fifth of the US level. Yet Cuba’s achievements in boosting literacy and public health are substantial. Life expectancy in Cuba equals that of the US, and is much higher than in most of Latin America. Cuban doctors have played an important role in disease control in Africa in recent years.

Normalization of diplomatic relations creates two very different scenarios for US-Cuba relations. In the first, the US reverts to its bad old ways, demanding draconian policy measures by Cuba in exchange for “normal” bilateral economic relations. Congress might, for example, uncompromisingly demand the restitution of property that was nationalized during the revolution; the unrestricted right of Americans to buy Cuban land and other property; privatization of state-owned enterprises at fire-sale prices; and the end of progressive social policies such as the public health system. It could get ugly.

In the second scenario, which would constitute a historic break with precedent, the US would exercise self-restraint. Congress would restore trade relations with Cuba, without insisting that Cuba remake itself in America’s image or forcing Cuba to revisit the post-revolution nationalizations. Cuba would not be pressured to abandon state-financed health care or to open the health sector to private American investors. Cubans look forward to such a mutually respectful relationship, but bristle at the prospect of renewed subservience.

This is not to say that Cuba should move slowly on its own reforms. Cuba should quickly make its currency convertible for trade, expand property rights, and (with considerable care and transparency) privatize some enterprises.

Such market-based reforms, combined with robust public investment, could speed economic growth and diversification, while protecting Cuba’s achievements in health, education, and social services. Cuba can and should aim for Costa Rican-style social democracy, rather than the cruder capitalism of the US. (The first author here believed the same about Poland 25 years ago: It should aim for Scandinavian-style social democracy, rather than the neo-liberalism of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.)

The resumption of economic relations between the US and Cuba is therefore a test for both countries. Cuba needs significant reforms to meet its economic potential without jeopardizing its great social achievements. The US needs to exercise unprecedented and unaccustomed self-control, to allow Cuba the time and freedom of maneuver it needs to forge a modern and diversified economy that is mostly owned and operated by the Cuban people themselves rather than their northern neighbors.

Our world is immensely wealthy and could easily finance a healthy start in life for every child on the planet. A small shift of financing from wasteful US military spending to global funds for health and education, or a very small levy on tax havens’ deposits, would make the world vastly fairer, safer, and more productive.

In 2015, around 5.9 million children under the age of five, almost all in developing countries, died from easily preventable or treatable causes. And up to 200 million young children and adolescents do not attend primary or secondary school, owing to poverty, including 110 million through the lower-secondary level, according to a recent estimate. In both cases, massive suffering could be ended with a modest amount of global funding.

Children in poor countries die from causes – such as unsafe childbirth, vaccine-preventable diseases, infections such as malaria for which low-cost treatments exist, and nutritional deficiencies – that have been almost totally eliminated in the rich countries. In a moral world, we would devote our utmost effort to end such deaths.

In fact, the world has made a half-hearted effort. Deaths of young children have fallen to slightly under half the 12.7 million recorded in 1990, thanks to additional global funding for disease control, channeled through new institutions such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria.

When I first recommended such a fund in 2000, skeptics said that more money would not save lives. Yet the Global Fund proved the doubters wrong: More money prevented millions of deaths from AIDS, TB, and malaria. It was well used.

The reason that child deaths fell to 5.9 million, rather to near zero, is that the world gave only about half the funding necessary. While most countries can cover their health needs with their own budgets, the poorest countries cannot. They need about $50 billion per year of global help to close the financing gap. Current global aid for health runs at about $25 billion per year. While these numbers are only approximate, we need roughly an additional $25 billion per year to help prevent up to six million deaths per year. It’s hard to imagine a better bargain.

Similar calculations help us to estimate the global funding needed to enable all children to complete at least a high-school education. UNESCO recently calculated the global education “financing gap” to cover the incremental costs – of classrooms, teachers, and supplies – of universal completion of secondary school at roughly $39 billion. With current global funding for education at around $10-15 billion per year, the gap is again roughly $25 billion, similar to health care. And, as with health care, such increased global funding could effectively flow through a new Global Fund for Education.

Thus, an extra $50 billion or so per year could help ensure that children everywhere have access to basic health care and schooling. The world’s governments have already adopted these two objectives – universal health care and universal quality education – in the new Sustainable Development Goals.

An extra $50 billion per year is not hard to find. One option targets my own country, the United States, which currently gives only around 0.17% of gross national income for development aid, or roughly one-quarter of the international target of 0.7% of GNI for development assistance.

Sweden, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom each give at least 0.7% of GNI; the US can and should do so as well. If it did, that extra 0.53% of GNI would add roughly $90 billion per year of global funding.

The US currently spends around 5% of GDP, or roughly $900 billion per year, on military-related spending (for the Pentagon, the CIA, veterans, and others). It could and should transfer at least $90 billion of that to development aid. Such a shift in focus from war to development would greatly bolster US and global security; the recent US wars in North Africa and the Middle East have cost trillions of dollars and yet have weakened, not strengthened, national security.

A second option would tax the global rich, who often hide their money in tax havens in the Caribbean and elsewhere. Many of these tax havens are UK overseas territories. Most are closely connected with Wall Street and the City of London. The US and British governments have protected the tax havens mainly because the rich people who put their money there also put their money into campaign contributions or into hiring politicians’ family members.

The tax havens should be called upon to impose a small tax on their deposits, which total at least $21 trillion. The rich countries could enforce such a tax by threatening to cut off noncompliant havens’ access to global financial markets. Of course, the havens should also ensure transparency and crack down on tax evasion and corporate secrecy. Even a deposit tax as low as 0.25% per year on $21 trillion of deposits would raise around $50 billion per year.

Both solutions would be feasible and relatively straightforward to implement. They would underpin the new global commitments contained in the SDGs. At the recent Astana Economic Forum, Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev wisely called for some way to tax offshore deposits to fund global health and education. Other world leaders should rally to his call to action.

Our world is immensely wealthy and could easily finance a healthy start in life for every child on the planet through global funds for health and education. A small shift of funds from wasteful US military spending, or a very small levy on tax havens’ deposits – or similar measures to make the super-rich pay their way – could quickly and dramatically improve poor children’s life chances and make the world vastly fairer, safer, and more productive. There is no excuse for delay.

Since the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, business interests and conservative politicians have warned that raising the minimum wage would be ruinous. Even modest increases, they’ve asserted, will cause the U.S. economy to hemorrhage jobs, shutter businesses, reduce labor hours, and disproportionately cast young people, so-called low-skilled workers, and workers of color to the bread lines. As recently as this year, the same claims have been repeated, nearly verbatim.

“Raise wages, lose jobs”, the refrain seems to go.

If the claims of minimum-wage opponents are akin to saying “the sky is falling,” this report is an effort to check whether the sky did indeed fall. In this report, we examine the historical data relating to the 22 increases in the federal minimum wage between 1938 and 2009 to determine whether or not these claims—that if you raise wages, you will lose jobs—can be substantiated. We examine employment trends before and after minimum-wage increases, looking both at the overall labor market and at key indicator sectors that are most affected by minimum-wage increases. Rather than an academic study that seeks to measure causal effects using techniques such as regression analysis, this report assesses opponents’ claims about raising the minimum wage on their own terms by examining simple indicators and job trends.

The results were clear: these basic economic indicators show no correlation between federal minimum-wage increases and lower employment levels, even in the industries that are most impacted by higher minimum wages. To the contrary, in the substantial majority of instances (68 percent) overall employment increased after a federal minimum-wage increase. In the most substantially affected industries, the rates were even higher: in the leisure and hospitality sector employment rose 82 percent of the time following a federal wage increase, and in the retail sector it was 73 percent of the time. Moreover, the small minority of instances in which employment—either overall or in the indicator sectors—declined following a federal minimum-wage increase all occurred during periods of recession or near recession. That pattern strongly suggests that the few instances of such declines in employment are better explained by the overall national business cycle than by the minimum wage.

These employment trends after federal minimum-wage increases are not surprising, as they are in line with the findings of the substantial majority of modern minimum-wage research. As Goldman Sachs analysts recently noted, citing a state-of-the-art 2010 study by University of California economists that examined job-growth patterns across every border in the U.S. where one county had a higher wage than a neighboring county, “the economic literature has typically found no effect on employment” from recent U.S. minimum-wage increases.1 This report’s findings mirror decades of more sophisticated academic research, providing simple confirmation that opponents’ perennial predictions of job losses when minimum-wage increases are proposed are rooted in ideology, not evidence.

KEY FINDINGS

The federal minimum wage has been raised a total of 22 times since its enactment in 1938. The simplest way to assess the claim that raising the minimum wage costs jobs is to treat each minimum-wage increase as a distinct event and look and see what happened to employment or other indicators one year later.

While opponents often broadly charge that raising the minimum wage “will cause job losses,” such increases disproportionately affect a select few employment sectors. The bulk of workers receiving raises as the result of minimum-wage increases are concentrated in a group of service industries—the two largest being restaurants and retail. For that reason, we examine employment trends, both overall and with a special focus on these indicator industries in which any adverse impact resulting from a higher minimum wage would most likely be evident.

Our findings are quite clear: in the nearly two dozen instances when the federal minimum wage has been increased, employment the following year has increased in the substantial majority of instances.

This pattern of increased job growth following minimum-wage increases holds true both for general labor-market indicators as well as those for industries heavily affected by minimumwage increases:

What’s more, looking more closely at the relative handful of instances in which employment decreased—whether total employment, or employment in our key indicator sectors—it is also clear that those declines were likely driven by factors other than the higher minimum wage.

Specifically, in five out of eight instances where either total or industry-specific employment took a negative turn during the one-year period following a minimum-wage increase, the employment decreases happened during periods when the U.S. economy was officially in recession.

In the remaining three instances, a recession was just around the corner (the decline shown during the period of March 1956-1957 would be swiftly followed by the Recession of 1958, during which time the U.S. automotive industry saw its worst year since World War II), or the economy was still recovering from a recessionary period (decreases in both the April 1991-1992 and July 2009-2010 periods occurred just months after a recessionary period had technically ended, but the economy was still feeling the effects).

In each of the relatively few instances in which employment declined following a federal minimum-wage increase, the economy was either in recession or near a recession. In all other instances, employment grew after the federal minimum wage went up. These patterns show that federal minimum-wage increases have not correlated with reductions in jobs, and in the few instances where they have, the decline was better explained by the business cycle than by the minimum wage.

This is not to say that individual firms may not change their employment decisions in response to higher minimum wages. But it shows that in the aggregate, across firms and across the economy, there is no pattern of reduced employment when the federal minimum wage goes up—and the few instances when employment has gone down after wage increases have been during recessions or near recessions—circumstances that much more plausibly explain the observed employment reductions than the modest minimum-wage increases.

CONCLUSION

For decades, minimum-wage opponents have been doom-saying about the likely impact of higher wages on the economy. But review of the best evidence makes clear that their predictions have not been borne out by real-world results. Our analysis of simple job-growth data—both economy-wide and in the industries most affected by higher minimum wages— shows that there is no correlation between minimum-wage increases and reduced employment levels. As those results mirror the findings of decades of more sophisticated academic research, they provide simple confirmation that opponents’ perennial predictions of job losses are rooted in ideology, not evidence.

This film from 350.org describes the political situation around climate change and how the Paris Agreement was not enough, specifically because it is not a legally binding contract.

It calls on individuals and communities to step into this issue and fight to limit climate change where politics have fallen short. It uses examples of communities that stood together and stood up to corporate interests to demonstrate that through organization, civil disobedience, and making others aware of the situation, strides can be made.

These communities include an area in the Philippines where they were able to oust a dictatorship that had many dirty and harmful energy projects. A community in Canada that stopped a Shell project, a community in Turkey that was successful at preventing the construction of a plant, and a movement in Germany that stopped lignite machines in protest of the destruction of a town that produced 100% of its energy from renewables simply because it sat on fossil fuel deposits.

The video encourages the viewers to make their voices heard because it is important to grab public attention on this issue to galvanize support.

It ends with the call to action: “The limits of the impossible are meant to be moved. How many people are active and engaged on this issue? All we have is a choice whether to be one of those people”

The diplomats have done their job, concluding the Paris climate agreement in December. And political leaders gathered… at the United Nations to sign the new accord. But implementation is surely the tough part. Governments need a new approach to an issue that is highly complex, long term, and global in scale.

At its core, the climate challenge is an energy challenge. About 80% of the world’s primary energy comes from carbon-based sources: coal, oil, and gas. When burned, they emit the carbon dioxide that causes global warming. By 2070, we need a world economy that is nearly 100% carbon-free to prevent global warming from running dangerously out of control.

The Paris agreement recognizes these basic facts. It calls on the world to cut greenhouse-gas emissions (especially CO2) to net-zero levels in the second half of the century. To this end, governments are to prepare plans not only to the year 2030 (the so-called Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs), but also to mid-century (the so-called Low-Emission Development Strategies, or LEDS).

The world’s governments have never before attempted to remake a core sector of the world economy on a global scale with such an aggressive timeline. The fossil-fuel energy system was created step by step over two centuries. Now it must be comprehensively overhauled in just 50 years, and not in a few countries, but everywhere. Governments will need new approaches to develop and implement their LEDS.

There are four reasons why politics as usual will not be sufficient. First, the energy system is just that: a system of many interconnected parts and technologies. Power plants, pipelines, ocean transport, transmission lines, dams, land use, rail, highways, buildings, vehicles, appliances, and much more must all fit together into a working whole.

Such a system cannot be overhauled through small incremental steps. A deep overhaul requires system-wide re-engineering to ensure that all parts continue to work effectively together.

Second, there are still many large technological uncertainties in moving to a low-carbon energy system. Should vehicles be decarbonized through battery-electric power, hydrogen fuel cells, or advanced biofuels? Can coal-fired power plants be made safe through carbon capture and storage (CCS)? Will nuclear energy be politically acceptable, safe, and low cost? We must plan investments in research and development to resolve these uncertainties and improve our technological options.

Third, sensible solutions require international energy cooperation. One key fact about low-carbon energy (just like fossil fuels) is that it is not generally located where it will ultimately be used. Just as coal, oil, and gas must be transported long distances, so wind, solar, geothermal, and hydropower must be moved long distances through transmission lines and through synthetic liquid fuels made with wind and solar power.

Fourth, there are of course powerful vested interests in the fossil-fuel industry that are resisting change. This is abundantly clear in the US, for example, where the Republican Party denies climate change for the sole reason that it is heavily funded by the US oil industry. This is certainly a species of intellectual corruption, if not political corruption (it’s probably both).

The fact that the energy system involves so many complex interconnections leads to tremendous inertia. Shifting to a low-carbon energy system will therefore require considerable planning, long lead times, dedicated financing, and coordinated action across many parts of the economy, including energy producers, distributors, and residential, commercial, and industrial consumers. Policy measures such as a tax on carbon emissions can help to address some – but only some – challenges of the energy transition.

Here is another problem. If governments plan only 10-15 years ahead, as is typical in energy policy, rather than 30-50 years, they will tend to make poor system-related choices. For example, energy planners will move from coal to lower-carbon natural gas; but they will tend to underinvest in the much more decisive shift to renewable energy.

Similarly, they may opt to raise fuel standards for internal-combustion automobiles rather than to push the needed shift to electric vehicles. In this sense, planning 30-50 years ahead is vital not only to make the correct long-run choices, but also to inform the correct short-term choices. The UN’s Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project has shown how long-term plans can be designed and evaluated.

None of these challenges sits easily with elected politicians. The decarbonization challenge requires consistent policies over 30-50 years, while politicians’ time horizon is perhaps a tenth of that. Nor are politicians very comfortable with a problem that requires large-scale public and private financing, highly coordinated action across many parts of the economy, and decision-making in the face of ongoing technological uncertainties. Small wonder, then, that most politicians have shied away from this challenge, and that far too little practical progress has been made since the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change was signed in 1992.

One key step, I believe, is to remove these issues from short-term electoral politics. Countries should consider establishing politically independent energy agencies with high technical expertise. Of course, key energy decisions (such as whether to deploy nuclear energy or to build a new transmission grid) will require deep public participation, but planning and implementation should be free of excessive partisan politics and lobbying. Just as governments have successfully given their central banks some political independence, they should give their energy agencies enough leeway to enable them think and act for the long term.

With the Paris climate agreement now in force, we must move urgently to effective implementation.