Bill Moyers talks with Economic analyst Robert Reich about the new film Inequality for All. Opening in theaters across the country next week, the film aims to be a game-changer in our national discussion of income inequality.

Bill Moyers talks with Economic analyst Robert Reich about the new film Inequality for All. Opening in theaters across the country next week, the film aims to be a game-changer in our national discussion of income inequality.

The statutory objectives for monetary policy known as the “dual mandate” were imposed by Congress as part of the Federal Reserve by Act of 1913. The mandate charges the Federal Reserve with responsibility for achieving two broad macroeconomic goals: “maximum employment and stable prices.”

Much has been made (especially by those on the left) of the benefits of having a dual mandate. In contrast to the European Central Bank, which operates with a single mandate — price stability — the dual mandate is supposed to ensure a more balanced outcome in the public’s interest.

As Matt Yglesias put it:

“The idea of a “dual mandate” to pursue both price stability and maximum employment is that even if a pure look at inflation would lead the Fed to want tighter money, it ought to check out the employment situation and think twice before tightening if joblessness is widespread.”

But not everyone is so enamored with the idea of requiring the Fed to care as much about fighting unemployment as it does about restraining inflation. For example, not a single Republican expressed support for the dual mandate when the issue came up during a presidential debate on September 12, 2011.

“At the Republican presidential debate on Sept. 12, the major candidates argued that the Fed should instead focus squarely on the goal of long-run price stability.

Responding to a question about the Fed, Rick Santorum said: “make it a single charter instead of a dual charter” institution, and no candidate disagreed. Most piled on. “Its focus needs to be narrowed,” said Herman Cain. “We need to have a Fed that is working towards sound monetary policy,” said Rick Perry. “The Federal Reserve has a responsibility to preserve the value of our currency,” said Mitt Romney.”

Former Fed Chairman Paul Volker recently made a similar (but far more nuanced) argument with respect to the dual mandate.

“I know that it is fashionable to talk about a “dual mandate”—the claim that the Fed’s policy should be directed toward the two objectives of price stability and full employment. Fashionable or not, I find that mandate both operationally confusing and ultimately illusory. It is operationally confusing in breeding incessant debate in the Fed and the markets about which way policy should lean month-to-month or quarter-to-quarter with minute inspection of every passing statistic. It is illusory in the sense that it implies a trade-off between economic growth and price stability, a concept that I thought had long ago been refuted not just by Nobel Prize winners but by experience.

The Federal Reserve, after all, has only one basic instrument so far as economic management is concerned—managing the supply of money and liquidity. Asked to do too much—for example, to accommodate misguided fiscal policies, to deal with structural imbalances, or to square continuously the hypothetical circles of stability, growth, and full employment—it will inevitably fall short. If in the process of trying it loses sight of its basic responsibility for price stability, a matter that is within its range of influence, then those other goals will be beyond reach.”

Volker argues that the Fed would actually do a better job of maintaining high employment if it was freed of its dual mandate and simply assigned broad responsibility for maintaining price stability over time. Perhaps this position is not surprising, given that there was not a single mention of “maximum employment” in any of the Fed’s written directives while Volker was Chairman of the Federal Reserve. But his real beef stems from concerns about the “extraordinary” measures — Quantitative Easing (QE) in particular — the Fed has adopted in an effort to carry out the employment side of its mandate.

Volker is basically worried that the Fed is under too much pressure to bring down unemployment and that recent policy has introduced substantial risks in terms of inflation, financial instability and future credibility. On the unprecedented buying of Treasuries and mortgage backed securities, Volker says:

“The extraordinary commitment of Federal Reserve resources, alongside other instruments of government intervention, is now dominating the largest sector of our capital markets, that for residential mortgages. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to note that the Federal Reserve, with assets of $3.5 trillion and growing, is, in effect, acting as the world’s largest financial intermediator.”

He’s also worried about the use of “forward guidance” (i.e. the Fed’s promise to keep interest rates low for as long as unemployment remains above 6.5%, even if inflation creeps above its historical 2 percent target).

“The implicit assumption behind that siren call must be that the inflation rate can be manipulated to reach economic objectives—up today, maybe a little more tomorrow, and then pulled back on command. But all experience amply demonstrates that inflation, when deliberately started, is hard to control and reverse. Credibility is lost.”

It’s important to note that Volker isn’t suggesting that the dual mandate should be lifted so that the Fed can pursue a different set of policy goals. Quite the contrary! What he’s saying is that it would be easier for the Fed to deliver what everyone wants — higher employment and price stability — if we weren’t monitoring them so closely. Apparently, monetary policy is sort of like using a urinal — it’s just harder to do it with someone watching.

Anyway, my point is this. Nearly everyone seems to believe one or both of the following: (1) high levels of employment and low rates of inflation are worthwhile goals; and (2) the Fed is the right agency to deliver on these goals. I don’t dispute the former, but I often wonder about the latter. Heck, even the current Fed Chairman sometimes sounds unconvinced. An exasperated Ben Bernanke has confessed that, despite the extraordinary steps the Fed has taken to expedite the recovery, monetary policy is “not even the ideal tool.”

Whereas Bernanke has only hinted at the need for a fiscal partner, former Fed Chairman Marriner Eccles, openly advocated the use of fiscal policy as the most effective way to fight both unemployment and excessive inflation. In the depths of the Great Depression, Eccles pushed for a payroll tax cut, calling it “the most important single step that can be taken” to stimulate consumer buying power. Years later, just prior to the near tripling of U.S. war expenditures, Eccles urged lawmakers to raise the payroll tax in order to stave off an inflationary episode. Indeed, Eccles considered adjustments in fiscal policy (in this case an increase in the payroll) to be “the most effective anti-inflationary means of reducing purchasing power.”

Discussions like these continued after the war. Indeed, as Paul Samuelson notes in his classic text Economics (10th Ed), a serious debate took place after the national Commission on Money and Credit advocated greater reliance on fiscal policy to achieve the macro goals of full employment and price stability. The problem, as Samuelson explained, was that the Commission recommended that the President be given unilateral authority to adjust tax rates in response to changing macro conditions. He explained the opposition thusly:

“Philosophically, some reformers dislike the need to have human beings decide policy. They speak of a ‘government of laws and not of men.’ They advocate setting up automatic rules and mechanisms that would go into action without ever depending on human decisions. . . we have not yet arrived at a stage where any nation is likely to create for itself a set of constitutional procedures that displace need for discretionary policy formation and responsible human intelligence.”

This is basically what the Taylor Rule was supposed to do — i.e. remove political pressures/human agency from monetary policy by automating decisions about whether and by how much to adjust the federal funds rate. With waning evidence that the Fed has sufficient firepower to carry out its dual mandate, perhaps it’s time to develop a fiscal analogue to the Taylor Rule.

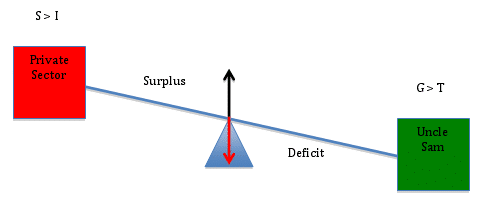

In a recent post (What Happens When the Government Tightens Its Belt?), I used a simple teeter-totter diagram to show how the government’s financial balance is related to the private sector’s financial balance in a closed economy. With only two sectors – government and non-government – I showed that a government deficit necessarily implies a surplus in the private sector.

As expected, this accounting truism ruffled the feathers of a flock of readers who have been programmed to launch into an anti-government tirade at the mere mention of the public sector and to regard the dangers of deficit spending as an unimpeachable fact. And while you’re certainly entitled to your own political views, you are not, as Senator Moynihan famously said, entitled to your own facts.

Other, less impenetrable minds, agreed that the private sector’s financial position must improve as the government’s deficit increases in a closed economy, but they argued that I had not demonstrated anything meaningful because I ignored the financial flows that occur in an open economy.

I still hope to convince both groups that they are acting against their own economic interests when they support policies to balance the budget or reduce the deficit, either by raising taxes or cutting government expenditures. So let’s continue the exercise and, as promised, extend the argument to the more realistic open-economy in which we actually live.

In an open economy, income flows into and out of the domestic economy as residents and foreigners buy goods and services (exports minus imports), make and receive payments such as interest and dividends (factor income) and make net transfer payments (such as foreign aid). Each country keeps track of these payments using a balance of payments (BOP) account, which summarizes the international monetary transactions that take place between the home country and the rest of the world. The BOP has two primary components – the current account and the capital account – and we can use either one to show whether, on balance, money is flowing into or out of a country.

When we incorporate these international flows, we transform the closed-economy accounting identity I used in my previous post:

[1] Domestic Private Surplus = Government Deficit

into the open-economy accounting identity shown below:

[2] Domestic Private = Government + Current Account

Surplus Deficit Balance

or, equivalently,

[3] Domestic Private = Government + Capital Account

Surplus Surplus Balance

When the current account balance is positive, it means that we in the private sector (households and domestic firms) are accumulating net financial claims on foreigners. When it is negative, they are accumulating net financial claims on us. Thus, a positive current account implies a negative capital account and vice versa.

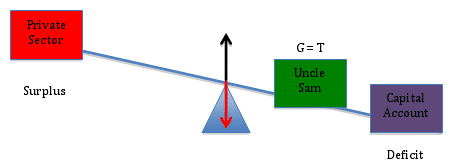

To see this in the context of the teeter-totter model, let’s initially hold the public sector’s balance constant at zero (i.e. let’s assume the government is balancing its budget so that G = T). With the government budget in balance, Uncle Sam is a “weightless” entity on the teeter-totter, so that the private sector’s financial position will simply reflect the “weight” of the capital account. Suppose, first, that the current account is in surplus (i.e. the capital account shows an equivalent deficit):

The image above depicts the benefit (to the private sector) of a current account surplus (a.k.a a capital account deficit), and it is the outcome that many of you accused me of sidestepping in my previous post. Of course, the U.S. does not have a current account surplus, so let’s address that point before moving on. (And lest anyone begin to hyperventilate, I’ll also address the fact that G ≠ T). First, the current account.

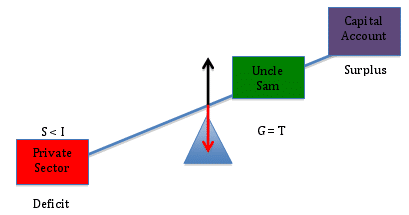

Sticking with (G = T) for the moment, we can show how a current account deficit impacts the private sector’s financial position. As the capital account moves from deficit (diagram above) into surplus (diagram below), we see that the private sector’s financial position moves from surplus into deficit.

But does this all of this hold true in the real world, or is it some kind of economic chicanery? Let’s check the facts.

Equations [2] and [3] above are not based on economic theory. They are accounting identities that always “add up” in the real world. So let’s firm up the discussion about the implications of government “belt tightening” by running through some examples using the real world data found in the table below (Hat tip to Scott Fullwilir for sharing the file. All of the data comes from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) and the Flow of Funds.)

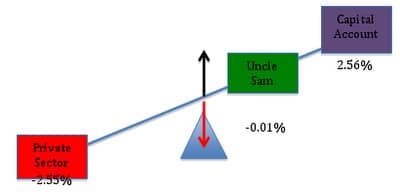

Let’s begin with the data from 1998 (Q3), when the public sector deficit was just 0.01% of GDP and the current account deficit was 2.56% of GDP. Plugging these numbers into equation [2] above, the identity tells us (and the data in the table confirm) that the private sector’s balance must have been:

[2] Domestic Private Sector’s Balance = 0.01% + (-2.56% )= -2.55%

Here, we can see that the private sector’s financial position was deteriorating because it was making large (net) payments to foreigners. Because this loss of financial resources was not offset by the public sector, the private sector’s financial position deteriorated.

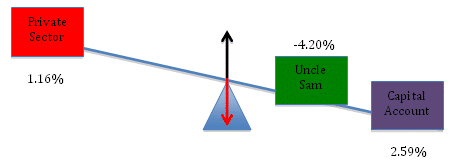

To see how a bigger government deficit would have improved the private sector’s financial position, let’s look at the data from 1988 (Q1). As a percent of GDP, the current account balance was 2.59%, nearly the same as before, while the government’s deficit came in at a much higher 4.2% of GDP. We can use Equation [2] to see effect of the larger budget deficit:

[2] Domestic Private Sector’s Balance = 4.2% + (-2.59%) = 1.61%

In this period, the private sector ends up with a surplus because the government’s deficit was large enough to more than offset the negative effect of the current account deficit.

Again, this is simply a property of the sectoral balance sheet identities. Whenever the government’s deficit is too small to offset a deficit in the current account, the private sector will experience a net loss. The result my ruffle your feathers, but it is an unimpeachable fact.

So let’s go back to President Obama’s comment and the reason I wrote this blog in the first place. The President said:

“Small businesses and families are tightening their belts. Their government should, too.”

Wrong! When we tighten our belts, it means that we are trying to build up our savings. We do this by spending less. But spending drives our economy. Sales create jobs. So unless Obama has a secret plan to reverse three decades of current account deficits, the Government needs to loosen its belt when we tighten ours. If it doesn’t, then millions of us will lose our shirts.

*An aside: I am aware that I have said nothing about the usefulness of the spending projects, the waste and inefficiency that exists with many government programs, cronyism, inequality, etc., etc. These are legitimate and important questions, but they are not the focus of this analysis. I wrote this series of blogs to try to get people to understand the interplay between the private, public and foreign sectors’ balance sheets.

Imagine two people sitting on opposite ends of a 15-foot teeter-totter. The laws of physics dictate that the seesaw will balance if the product of the first mass (w1) and its distance (d1) from the fulcrum (i.e. the balancing point) is equal to the product of the other mass (w2) and its distance (d2) from the fulcrum.

Thus, the physicist can show that the teeter-totter will be in balance when the fulcrum is placed 6 feet from the end holding a 150lb person and 9 feet from the end holding a 100lb person. Moreover, the laws of physics ensure that an imbalance will arise if the mass or the relative position of one of the people is changed.

The laws of accounting allow us to demonstrate that similarly powerful concepts apply to the science of economics. Beginning with the simple identity for GDP in a closed economy, we have:

[1] Y = C + I + G, where:

For economists, this is as obvious as stating that a linear foot is the sum of 12 sequential inches. It simply recognizes that the total amount of money spent buying newly produced goods and services will yield an equivalent income to the sellers of these products. Thus, it demonstrates that expenditures are a source of income.

Once earned, income can be allocated in one of three ways. At the end of the day, all income (Y) will be spent (C), saved (S) or used in payment of taxes (T):

[2] Y = C + S + T

Since they are equivalent expressions for Y, we can set equation [1] equal to equation [2], giving us:

C + I + G = C + S + T

Or, after canceling (C) from both sides and moving terms around:

[3] (S – I) = (G – T)

Equation [3] shows that there is a direct relationship between what’s happening in the private sector (S – I) and what’s happening in the public sector (G – T). But it is not the one that Pete Peterson, Erskin Bowles, or President Obama would have you believe. And I want you to understand why they are wrong.

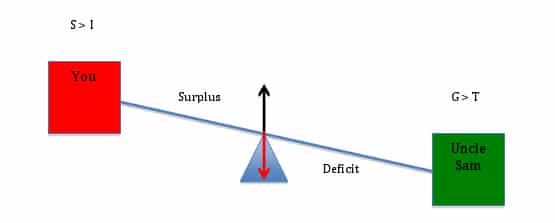

To understand the argument, imagine that you and Uncle Sam are sitting on opposite ends of a teeter-totter. You represent the private sector, and your financial status is given by (S – I). Your budget can be in balance (S = I), in deficit (S < I) or in surplus (S > I). When your financial status is positive (S > I), you are net saving. When your financial status is negative (S < I), you are net borrowing. Uncle Sam’s financial status is equal to (G – T), and, like yours, his budget may be balanced (G = T), in deficit (G > T) or in surplus (G < T). When you interact, only three outcomes are possible.

First, it is conceivable that (S = I) and (G = T) so that (S – I) = 0 and (G – T) = 0. When this condition holds, the teeter-totter will level off with each of you experiencing a balanced budget.

In the above scenario, the government is balancing its receipts (T) and expenditures (G), and you are balancing your savings and investment spending. There is no net gain/loss.

But suppose the government begins to spend more than it collects in taxes (i.e. G > T). How will Uncle Sam’s deficit affect your position on the teeter-totter? The answer is as straightforward as increasing the mass of the person on the right-hand side of the seesaw. As Uncle Sam’s financial position turns negative, your financial position turns positive.

This should make intuitive as well as mathematical sense, because when Uncle Sam runs a deficit, you receive more financial assets than you lose through taxation. Put simply, Uncle Sam’s deficit lifts you into a surplus position. Moreover, bigger deficits mean bigger surpluses for you.

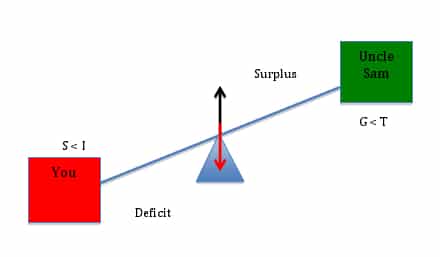

Finally, let’s see what happens when Uncle Sam tightens his belt. Suppose, for example, that we were able to duplicate the much-coveted surpluses of 1999-2001. What would (and did!) happen to the private sector’s financial position?

Because the economy’s financial flows are a closed system – every payment must come from somewhere and end up somewhere – one sector’s surplus is always the other sector’s deficit. As the government “tightens” its belt, it “lightens” its load on the teeter-totter, shifting the relative burden onto you.

This is not rocket science, but it appears to befuddle scores of educated people, including President Obama, who said, “small businesses and families are tightening their belts. Their government should, too.” This kind of rhetoric may temporarily boost his approval ratings, but the policy itself will undermine the efforts of the very families and small businesses that are trying to improve their financial positions.

In the fall of 1965 A. Philip Randolph, prominent economists, allies from the labor movement and others who had participated in the 1963 March on Washington, began working on what they called “A Freedom Budget For All Americans”.

John Nichols writing fifty years later in The Nation (United States) listed as its goals “the abolition of poverty, guaranteed full employment, fair prices for farmers, fair wages for workers, housing and healthcare for all, the establishment of progressive tax, and fiscal policies that respected the needs of working families.”

Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King, Jr., worked with Randolph on the Freedom Budget document which was advanced in 1966, determined to win the “full and final triumph of the civil rights movement, to be achieved by going beyond civil rights, linking the goal of racial justice with the goal of economic justice for all people in the United States” and doing so “by rallying massive segments of the 99% of the American people in a powerfully democratic and moral crusade.” The proposals of Freedom Budget included a job guarantee for everyone ready and willing to work, a guaranteed income for those unable to work or those who should not be working, and a living wage to lift the working poor out of poverty; such policies provided the cornerstones for King’s Poor People’s Campaign.

Download: A Freedom Budget For All Americans

Excerpted from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s message to Congress on the State of the Union. This was proposed not to amend the Constitution, but rather as a political challenge, encouraging Congress to draft legislation to achieve these aspirations. It is sometimes referred to as the “Second Bill of Rights.”

It is our duty now to begin to lay the plans and determine the strategy for the winning of a lasting peace and the establishment of an American standard of living higher than ever before known. We cannot be content, no matter how high that general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people — whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth — is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure.

This Republic had its beginning, and grew to its present strength, under the protection of certain inalienable political rights — among them the right of free speech, free press, free worship, trial by jury, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures. They were our rights to life and liberty.

As our nation has grown in size and stature, however — as our industrial economy expanded — these political rights proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness.

We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. “Necessitous men are not free men.” People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.

In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident. We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all — regardless of station, race, or creed.

Among these are:

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.

America’s own rightful place in the world depends in large part upon how fully these and similar rights have been carried into practice for our citizens.