Of the many giveaways to the super-rich in the Republican tax bill, the elimination of the estate tax stands out. This tax, the government’s most progressive source of revenue, does not affect 99.8 percent of Americans. Rather, it is paid by Republicans’ billionaire donors.

The United States has the largest number of billionaires in the world; their combined wealth is measured in the trillions of dollars. Perhaps not surprisingly, Republican politicians, whose campaigns the billionaires fund, want to repeal the estate tax, so the privileged children of those donors will be even richer. To use Donald Trump’s words, eliminating the federal estate tax is “a big, beautiful Christmas present” to super-privileged children — those born to multi-millionaires and billionaires.

Our nation is founded on the idea that we are created equal. The reality is that children of billionaires have many opportunities denied to the rest of us. Instead of making those children even richer and more privileged, here’s a better idea: If Republicans don’t want the revenue from that top 0.2 percent of wealthiest Americans to run the government, let’s dedicate it to Social Security and use it to expand those modest but vital benefits for everyone.

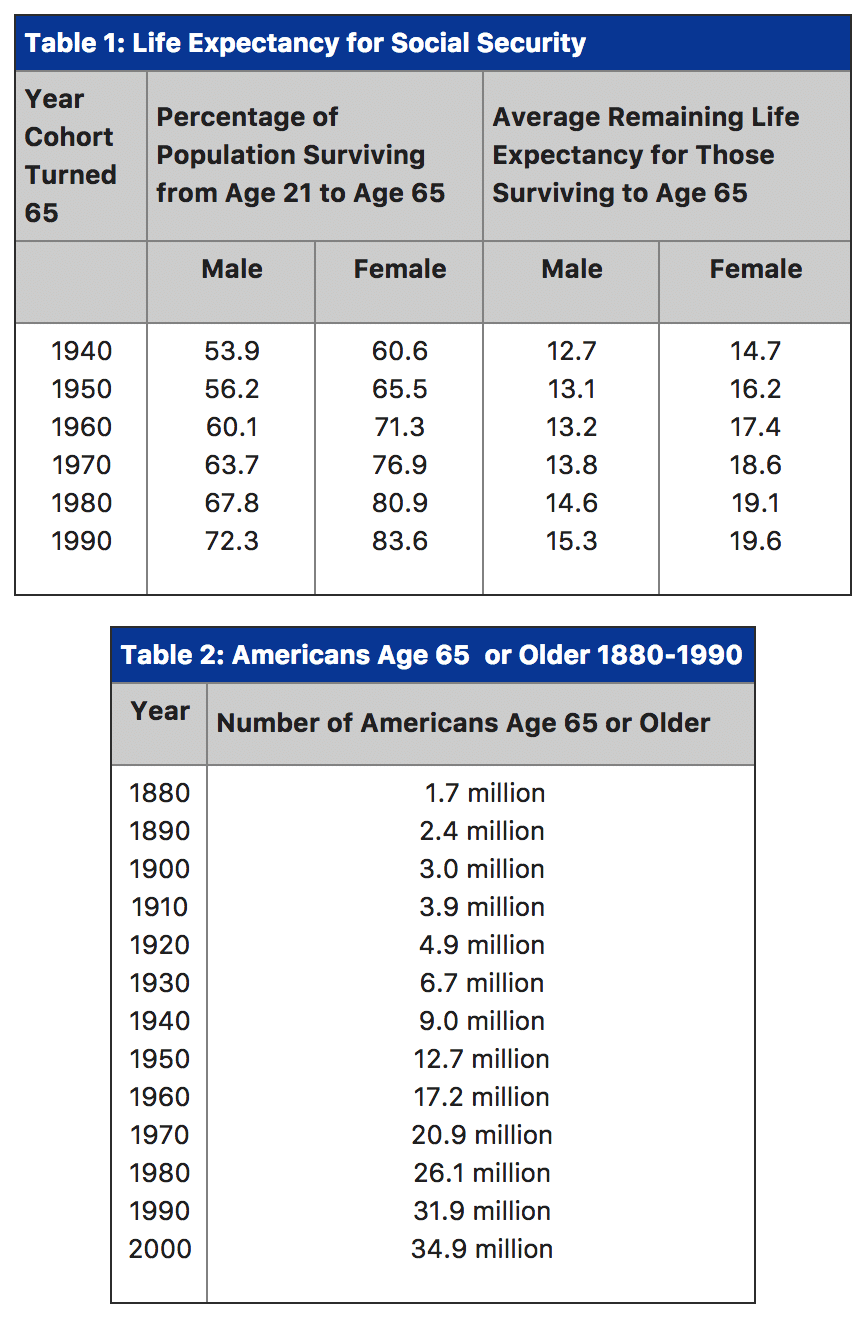

There are sound reasons for doing so. As a result of tax giveaways, the deregulation of Wall Street, and other policies favoring the rich, we have seen enormous wealth redistributed upwards to the most affluent Americans over the last thirty-five years. Meanwhile, the rest of us have been running in place or, worse, falling behind.

Rising inequality is a key driver of the retirement income crisis facing our country. It’s all but impossible for working- and middle-class families to prepare for retirement when nearly all of the income gains are going to the wealthiest 1 percent of the population.

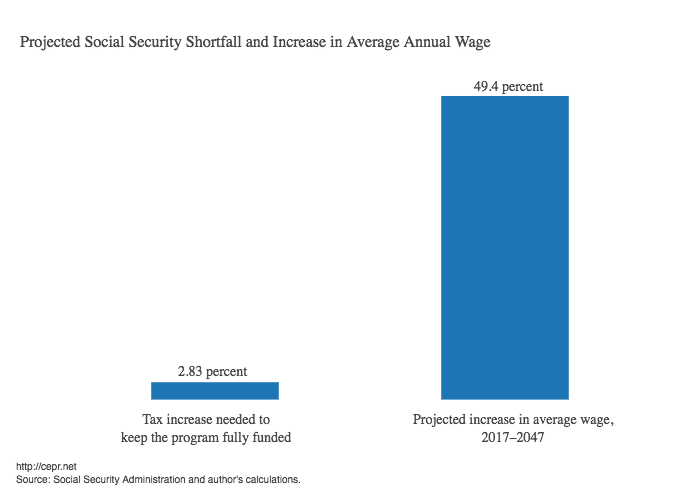

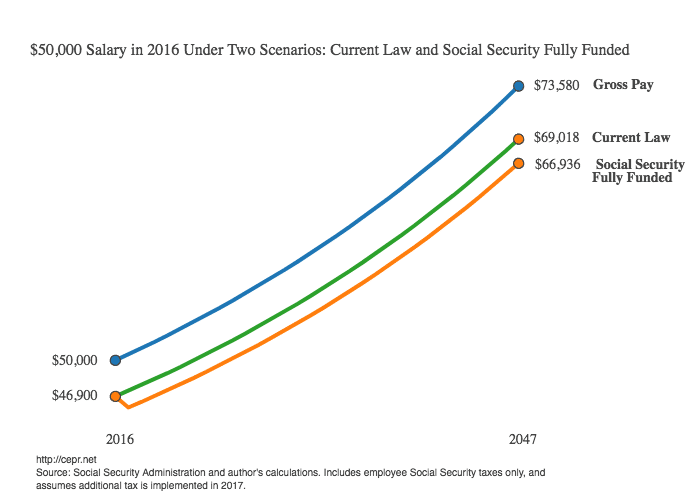

Inequality is also a major factor behind Social Security’s projected modest funding shortfall. The vast majority of workers contribute to Social Security with every paycheck, but when their wages are stagnant, so are their Social Security contributions. The percentage of wages paid as current cash compensation has also declined sharply as health insurance has accounted for a bigger and bigger portion of employee compensation.

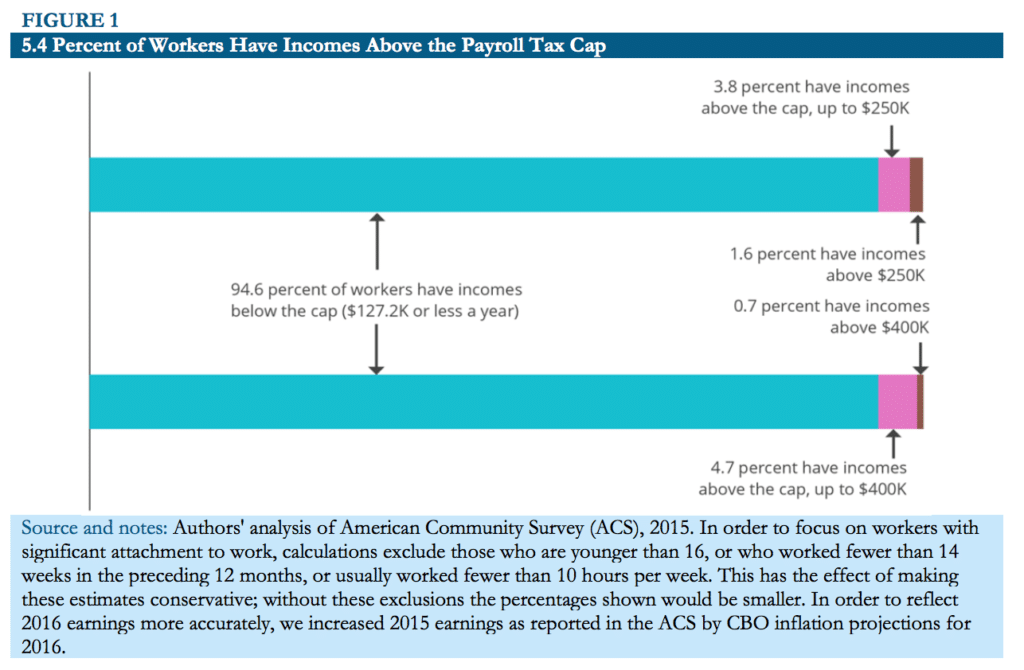

Meanwhile, the bulk of income gains captured by the wealthy either fall above Social Security’s maximum earnings contribution cap (currently $127,200), or are unearned income on which they do not pay Social Security contributions.

Since the earnings of high-income workers have increased much more rapidly than the average in the last several decades, Social Security now covers only about 82 percent of all wages. In 2016 alone, those at the top paid $80 billion less to Social Security, only because the cap has slipped from covering 90 percent of wages, as Congress intended, to 82 percent today. Those are billions of dollars that should have gone to Social Security but instead stayed in the pockets of the wealthiest among us. Unquestionably, the richest are not paying their fair share into Social Security.

The idea of scrapping the cap – eliminating the annual limit on wages subject to Social Security – is one that most Americans favor. Congress should do this. But that simply requires the wealthy to pay the same rate on earned income as everyone else. Most of their wealth is in stocks and other unearned income, which is currently shielded, so that none of it goes to Social Security.

Given the role of wealth and income inequality in creating both the retirement income crisis and Social Security’s modest shortfall, it is only fair that billionaires contribute more. Opponents of the federal estate tax like to call it a death tax. But what could be more generous than to only tax the billionaires’ wealth once they are dead and gone?

Isn’t it more than fair that their heirs, who had nothing to do with creating the wealth, receive most of it, but not every single penny of it? Isn’t it more than fair that a small piece of all that wealth go to the rest of us, without whom that wealth would never have been amassed?

After all, that wealth would have been impossible without the highways, courts, military, and other expenditures all of us paid for through our taxes. Requiring the very wealthiest Americans to forgo a portion of their fortune — on a one-time basis, only after death — to improve the economic security of all seems a reasonable minimum to require of those who have benefited so greatly from America’s commonwealth (i.e. common wealth).

The idea of a tax on inherited wealth goes back to our country’s founding. This is not surprising. After all, our founders were rebelling against the British king and aristocracy, against inherited wealth and position.

Thomas Paine, famed as the author of Common Sense, also wrote Agrarian Justice, in which he advocated an estate tax. He argued that it should be used to pay for pensions for older Americans and people with disabilities. We have caught up to part of Thomas Paine’s vision by creating our Social Security system. Now, it’s time for us to catch up to the financing part.

The late Robert M. Ball, the longest serving Social Security commissioner and widely recognized as the foremost expert on our nation’s Social Security system, dedicated his life to protecting and expanding the program. Like Thomas Paine, he believed that the estate tax should be dedicated to Social Security.

[The best alternative is to propose] that the estate tax be dedicated to Social Security and used to expand benefits for everyone.

That would be in keeping with the wisdom of founder of the nation, Thomas Paine, and founder of Social Security, Robert Ball. Dedication of the estate tax to Social Security while increasing its benefits would begin to combat income inequality and address our looming retirement income crisis.