It is important to recognize changes in the seasons. Our country is undergoing a significant metamorphosis, which is likely to last several years, but we have an opportunity to help ensure that what emerges from this turmoil is more beautiful than what preceded. While there are plenty of problems we can dwell on, at the same time there are a number of very positive changes occurring that I believe are laying the groundwork for a better future. It is now our collective job to work toward making that happen.

One of the big shifts going on is in the economic arena, and it will have profound effects. A fresh perspective on the role of our nation’s currency is set to reshape the debate on public policy and government budgets. If you are not yet familiar with Modern Money Theory (MMT), it is time you get up to speed. A good place to start is with the work of Stephanie Kelton. Her recent New York Times piece How We Think About The Deficit Is Mostly Wrong provides an excellent introduction to this shift in thinking.

The Patriotic Millionaires have a powerful message about restoring political equality, fair pay for workers, and ending tax giveaways for the wealthy. However, we too must be careful not to fall into the trap of framing tax reforms and public policy in ways that reinforce the narrative that our government is fiscally constrained. It is not, and never will be.

Let me be clear. Raising taxes on the wealthy does not give our government any more spending power than what it already possesses. Whatever Congress authorizes is “affordable” since our government is self-financing. The Treasury and Federal Reserve coordinate to make all payments that Congress authorizes, no matter what levels of taxes are collected. As I have written previously, our advocacy for tax reform is about reducing excessive inequality and extreme wealth concentration that disrupts our democratic process, NOT about fundraising for the federal government.*

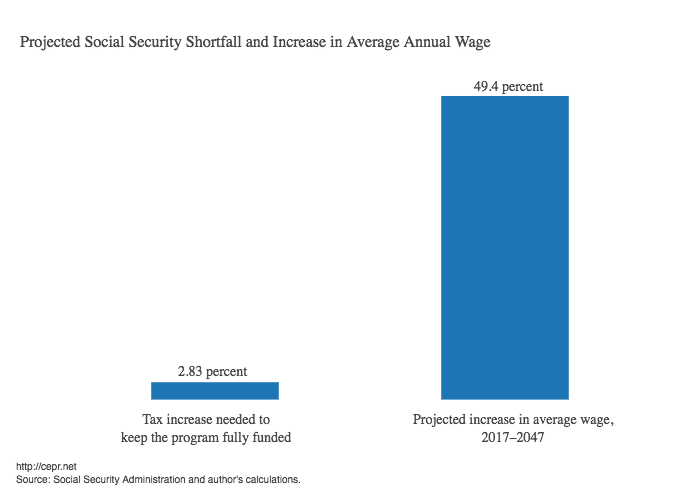

We must reframe fiscal policy debates away from the false narrative of a scarce money supply. This narrative forms the basis for the argument that Social Security and Medicare, among other government programs, are unaffordable. As Alan Greenspan tried to explain to a very disappointed Paul Ryan, “there is nothing to prevent the Federal Government from creating as much money as it wants and paying it to somebody.” There is no unfunded liability crisis.

We cannot give in to the temptation to link tax reforms that address inequities in our economy to the sustainability of important government programs.

- Firstly, it is economically inaccurate to state that federal taxes fund government spending. The government spends by crediting bank accounts, and taxes can only remove currency that prior government payments added. Taxes cannot be a source of funds.

- Secondly, we should vigorously defend programs such as Social Security from attacks simply because a government that issues its own currency will never be insolvent. Congress should simply approve a permanent living wage to senior citizens and authorize Treasury to make all payments as they become due, irrespective of taxes received or trust account balances. This is, of course, exactly how we pay for our wars.

- Finally, linking government programs and investments to a specific tax source leaves those programs subject to unnecessary cuts when tax receipts inevitably fall during recessions. Why would we want to link essential purpose services to business cycles?

It is time we ended the “pay for” mentality. We need to break the bad habit of pairing all of the government’s public investments with a tax, or of linking payments for government programs to the need for a more equitable tax code. They are two separate aspects of government policy, each to be debated on their own merits. This allows us to reframe the conversation on each issue back to how they best serve the public.

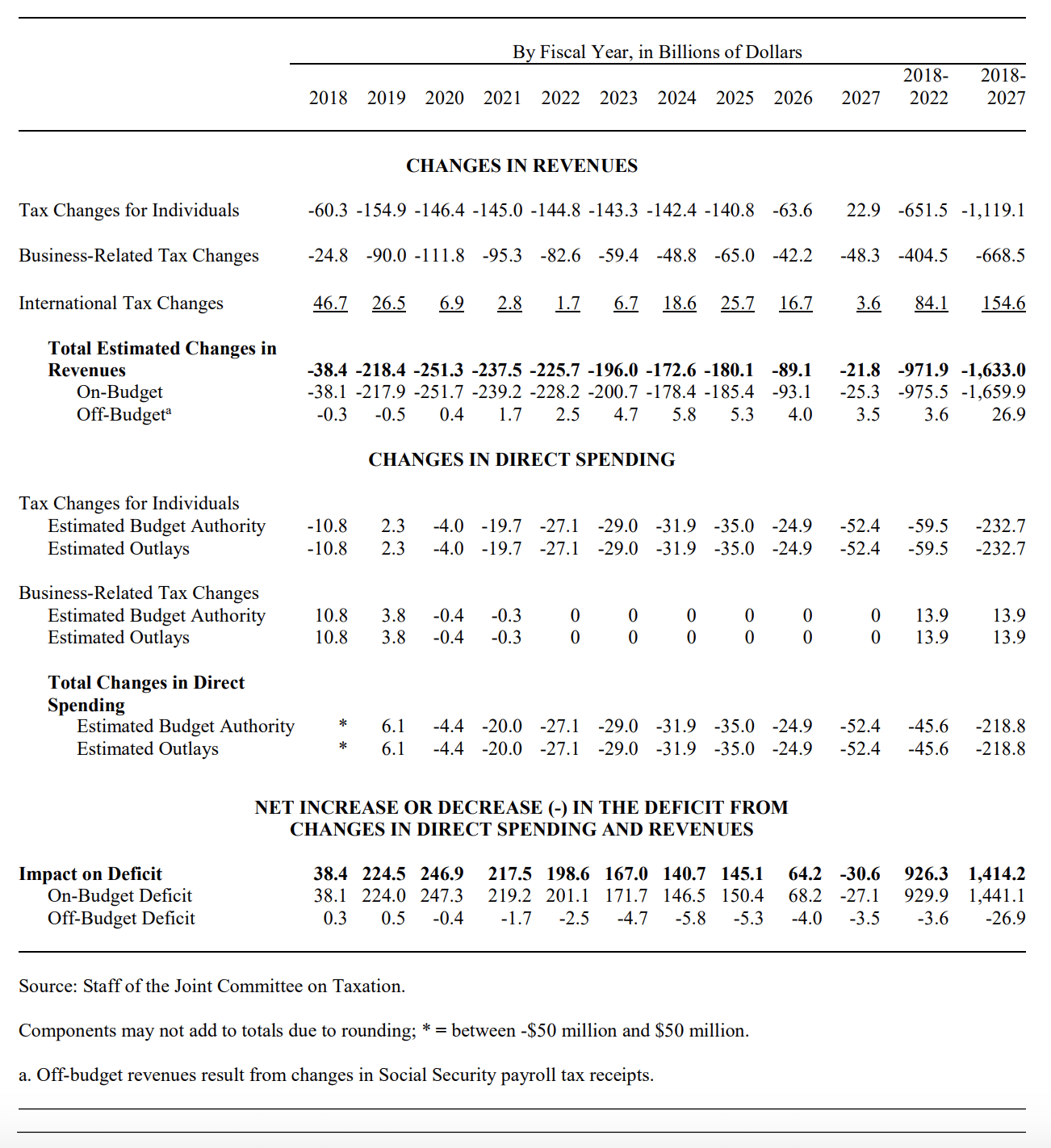

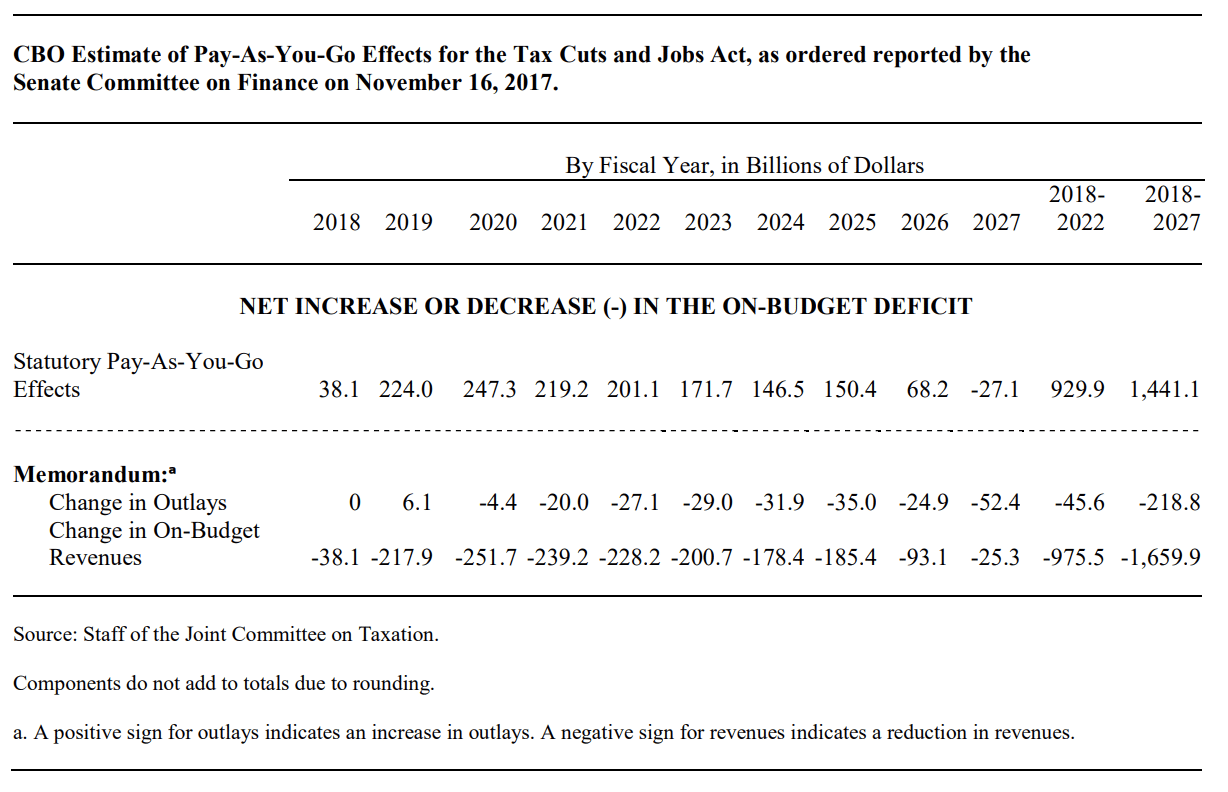

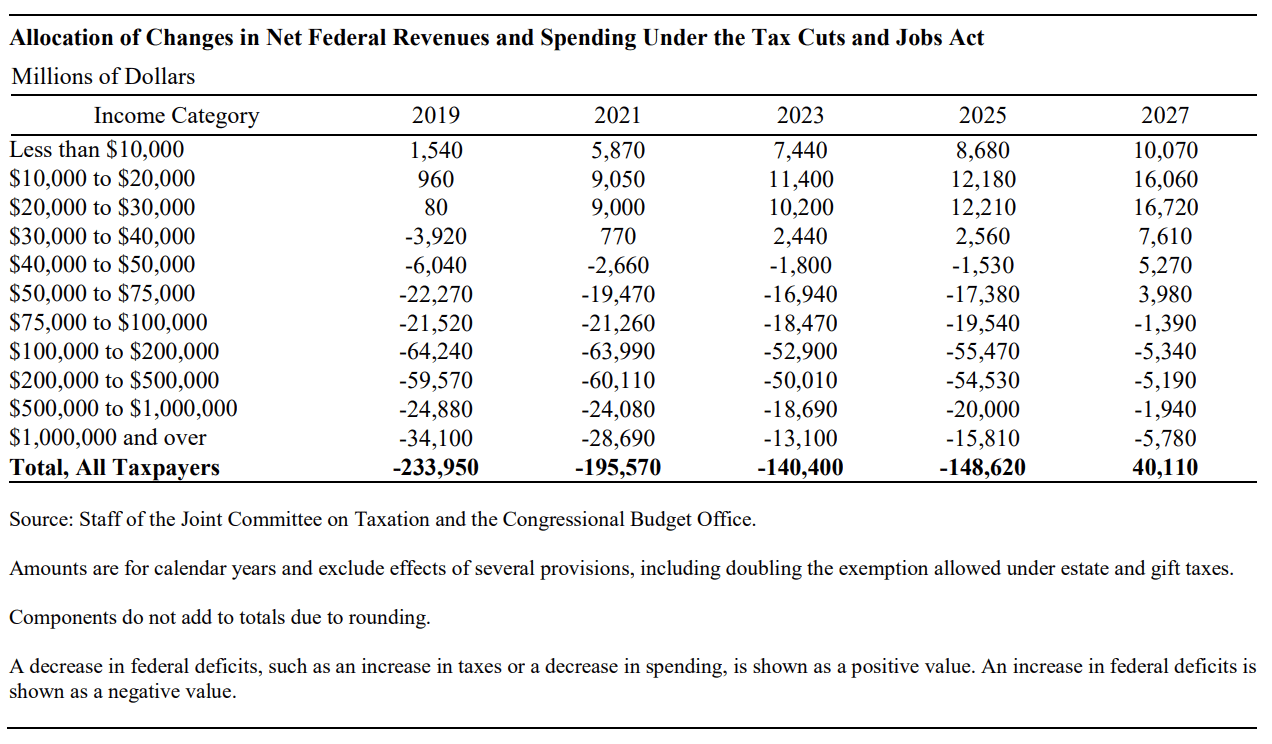

For example, the Republican Tax Plan was problematic not because it created a larger government deficit – something that is neither good nor bad in and of itself – but because it gave a massive handout of our public currency to the extremely wealthy, worsening an already excessively inequitable distribution of wealth, and doing nothing to create a more sustainable, shared prosperity.

Now, as Republicans seek to use the enlarged deficit to attack Social Security and Medicare, our response must be to expose their entire false premise – that larger deficits create unsustainable programs. Reducing funding for welfare programs is entirely a political choice, not an economic necessity. Such cuts are cruel public policy that hurts American families and have nothing to do with fiscal responsibility. We will separately argue for a less regressive FICA tax, but not because Social Security needs another source of funds, but rather so that we have a more just and fair tax system.

Our government is not constrained financially like a household. The deficit is not our primary guide for government budget and tax reform discussions. We Patriotic Millionaires have a compelling tax policy message that will reduce inequality and lead to a more prosperous economy for all. We also have a powerful message that our government can already afford to pay incomes to senior citizens, raise wages for its workers, cover the costs of health care, and forgive student loans.

Take care to reframe the debate over fiscal policy the right way. If you need help understanding how our modern monetary system works, you can check out my site Modern Money Basics. Together, we can shift our national conversation in a more positive direction and inspire hope in a better economy for all.

*Note that for state and local governments, which do not issue the public currency, taxes are essential for funding their budgets. The federal government as the issuer of our currency is unique.